This page addresses some of the questions about orders and opinion announcements that we have commonly received during our live blogs.

ORDERS

Question: What do you mean by orders?

Answer: When we talk about orders or the order list, we are usually referring to the actions that the court took at its most recent conference, which are reflected in a document (the order list) that the court releases to the public. The most common orders are those granting or denying review on the merits in a particular case (known as granting or denying cert, short for certiorari), but the court may also issue other orders related to petitions for review or in pending merits cases — for example, an order granting or rejecting a request to participate in an oral argument.

Question: What do you mean by certiorari?

Answer: A petition for certiorari, or cert petition, is a document filed in the Supreme Court asking the justices to review a lower court’s ruling in a case. This comes most often on appeal from one of the federal courts of appeals or a state’s highest appellate court. A cert petition usually gives a narrative account of the dispute and the ruling(s) below, followed by an argument outlining why the justices should review that ruling. The Supreme Court generally waits until the opposing party — that is, the side that prevailed in the lower court — weighs in on whether the justices should review the decision, or instead waives its right to do so, before acting on the petition. The justices have full discretion over whether to review the ruling, formally known as granting the petition for certiorari — or granting cert, for short. Four justices must vote to grant cert for the Supreme Court to hear the case. Thousands of cert petitions are filed each term, and the vast majority are denied.

Question: What is a CVSG?

Answer: CVSG stands for “call for the views of the solicitor general.” In most cases in which someone is seeking review of a lower court’s decision, the Supreme Court will issue a straightforward grant or denial. But sometimes the court will instead ask the federal government for its views on what the court should do with a particular petition for review, particularly in cases in which the government isn’t a party but may still have an interest — for example, because the interpretation of a federal statute is involved. In this scenario, the court will issue an order in which it invites the U.S. solicitor general, the federal government’s chief lawyer before the Supreme Court, to file a brief “expressing the views of the United States.” It isn’t an invitation in the sense that the federal government gets to decide whether it wants to file a brief at all, because the court expects the government to file. There is no deadline by which the government is required to file the brief; when the brief is filed, the government’s recommendation, although not dispositive, will carry significant weight with the court.

Question: What does it mean to relist a case?

Answer: When a case is relisted, the justices do not grant or deny review but instead will reconsider the case at their next conference. This will be reflected on the case’s electronic docket once the docket has been updated: You will see the words “DISTRIBUTED for Conference of [fill in date],” and then the next entry in the docket will usually say “DISTRIBUTED for Conference of [next conference after the previous entry, whenever that is].” It is almost impossible to know exactly what is happening when a particular case is relisted, but there are a few possibilities. One justice could be trying to pick up a fourth vote to grant review, one or more justices may want to look more closely at the case, a justice could be writing an opinion about the court’s decision to deny review, or the court could be writing an opinion to summarily reverse (that is, rule in favor of the petitioning party without briefing or oral argument on the merits) the decision below. In 2014, the court appears to have adopted a general practice of granting review only after it has relisted a case at least once; although we don’t know for sure, presumably the court uses the extra time resulting from a relist to make sure that the case is a suitable one for its review.

Question: What does it mean to reschedule a case?

Answer: When a case is rescheduled, the justices will consider the case at a different conference than the one for which it had originally been scheduled. Unlike relisted cases, which are considered at one conference and then set for reconsideration at the next conference, rescheduled cases are moved to a new conference without first having been considered at a prior conference. Rescheduled cases are similar to relisted cases, however, in that it is almost impossible to know exactly why a particular case has been rescheduled.

OPINIONS

Question: What opinions will the court issue on a given day?

Answer: Unlike some other courts, the Supreme Court doesn’t announce in advance which cases will be decided on a particular day. So normally, we don’t know which opinions we will get. The only time we have a good sense is the very last day, when the court issues its final rulings.

Question: What’s the last day the court will issue opinions?

Answer: We don’t know what the last day of the term will be. The justices normally try to issue all of their decisions by the end of June, but in 2024, the term’s final opinions came in early July.

Question: If a case is not decided by the end of the term, will it be reargued?

Answer: Ordinarily, yes, the court will order reargument during the next term. But it’s relatively rare for the court to order reargument, particularly if it hasn’t asked the lawyers in the case to address a new question.

Question: What are per curiam opinions?

Answer: A per curiam ruling is a ruling issued in the name of the court, without any specific author identified – for example, the court’s 2020 opinion in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. City of New York, which concluded that the Second Amendment claims based on the city’s old ban on the transport of guns were moot. Per curiam opinions in cases that were not briefed and argued on the merits are typically issued with the order list and not otherwise announced.

Question: How are the opinions released? Are the justices in the courtroom?

Answer: During the COVID-19 crisis, the opinions were released only on the court’s website. The justices have now returned to the courtroom to release opinions. The court posts opinions on its website after each announcement has been made. But although oral arguments are now live-streamed, the audio of the opinion announcements will not be available until it is released to the National Archives sometime in late fall or winter.

Question: How does the court decide the order in which opinions will be released on a given day?

Answer: The opinions are normally posted by author in order of reverse seniority. This means that if Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson has any opinions to announce, she goes first, followed by Justice Amy Coney Barrett, Justice Brett Kavanaugh, Justice Neil Gorsuch, and so on through the chief justice, who is always the most senior justice. However, there can be exceptions to this general reverse-seniority rule, generally when the justices are announcing decisions in two or more cases involving similar issues and it makes more sense to announce one first, even if it means disrupting the normal order for announcements.

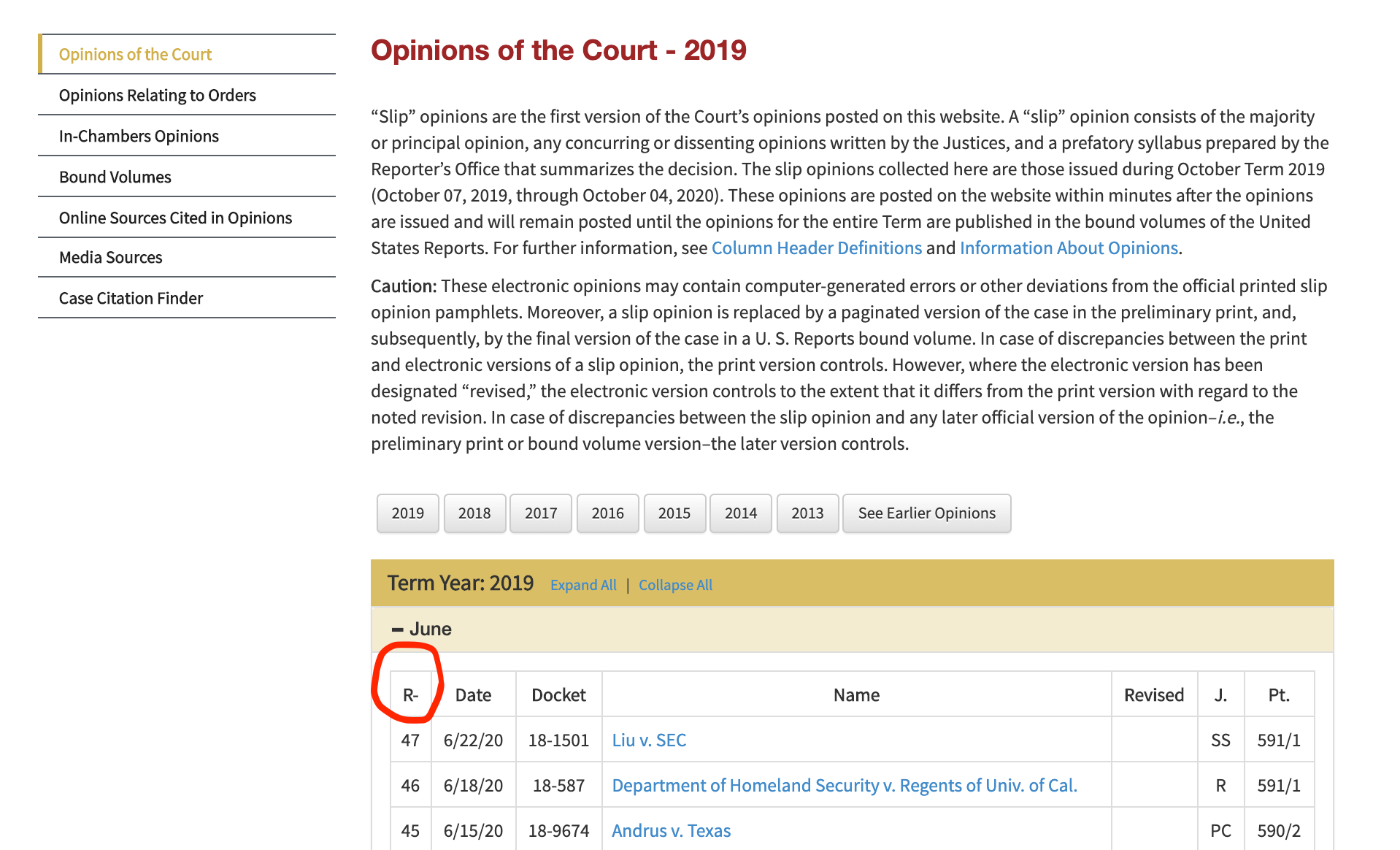

Question: What is the significance of “R” numbers?

Answer: The court does not state in advance how many opinions it will release, nor does it officially announce when it has finished releasing opinions for the day. However, the method that it uses to number the opinions – which we sometimes call the R-number system – serves as an unofficial (but so far reliable) signal that the court has released its final opinion for the day. When the opinions are eventually published in the U.S. Reports, the official bound version of the court’s opinions, they are published chronologically, with the opinions for a particular day published in order of seniority. The R number, which appears to the left of the opinion date/docket number/case name on the court’s website, refers to the order in which the opinion will appear in the U.S. Reports. But because opinions are announced in order of reverse seniority, the opinions on the court’s website can’t be assigned an R number until all of the opinions have been posted. Therefore, the posting of the R numbers is a sign that the court has finished issuing opinions for that day.

Question: Who decides which justice will write which opinion?

Answer: Shortly after the oral argument, the justices vote on a case. The most senior justice in the majority gets to assign the author of the opinion. He or she can assign it to himself or to a colleague he (or she) thinks will be able to hold the majority.

Question: Do the justices ever change their votes while the opinions are being drafted?

Answer: The justices do sometimes change their votes. But unless the news leaks from the court, the public generally does not know for sure that this has happened until much later – for example, when a justice leaves the court and releases her papers.

Question: Does the court notify the lawyers in advance when it is going to issue an opinion in their cases?

Answer: The court does not notify any of the lawyers in a case before it issues an opinion. So unless it is the last day before the summer recess, the lawyers (like the rest of us) don’t know whether they will get a decision in their cases.

Question: How can I find out when the next opinion day will be?

Answer: The court announces opinion days on the calendar on its website. Once it has finished hearing oral arguments for the term, opinion days appear as blue “non argument” days, and the court will indicate in its “Today at the Court” feature that it “may” announce opinions on a particular day.

Question: What are the logistics for the announcement of opinions?

Answer: There are two different arenas for the action when opinions are announced. The main event, of course, is in the courtroom. On opinion announcement days, the justices enter the courtroom to the traditional “Oyez!” cry from the court’s marshal, Gail Curley. Once the justices are seated, Chief Justice John Roberts then indicates that “Justice X has our opinion in No.-XX, [case name].” That justice reads a summary of the decision, which can range in length from quite short (especially if Justice Samuel Alito is reading) to fairly long (especially in high-profile cases). If there are dissenting opinions, a justice may opt to read from his or her dissent, but that is relatively rare.

If there is more than one opinion, the opinions are announced in order of reverse seniority. So after the first opinion announcement is finished, Roberts then indicates who has the next opinion, and he repeats this process until all of the opinions for the day have been released. At that point, the court will move on to any further proceedings for the day – admitting new lawyers to the Supreme Court bar, oral arguments – before the marshal gavels the session to a close. Before she does so, she normally indicates when the court will next be in session.

Some reporters choose to sit in the courtroom, where electronic devices are prohibited, for the opinion announcements. Many others remain on the first floor of the court building so that they can report on the opinions in (more or less) real time. The court’s press room is immediately adjacent to the court’s Public Information Office, where paper copies of the opinions are distributed as they are announced in the courtroom.

Shortly before 10 a.m., reporters gather in the PIO, where opinions are distributed from two desks. Reporters for the wire services – the Associated Press, Reuters, and Bloomberg – traditionally get first dibs on the opinions as they are released, because they are under the most pressure to report quickly. (Newcomers are cautioned to leave a clear path between the desks and the door to the press room, because those reporters can move fast once they get the opinions.)

Audio from the courtroom is piped into the PIO for opinion announcements. Once the chief justice indicates that a particular justice has the opinion in a particular case, the PIO begins to distribute the opinions to the waiting reporters. We then walk (or run, depending on the opinion) back to our desks in the press room with our paper copies of the opinions, known as slip opinions. As Amy starts to report on the opinion, she can hear the audio of the opinion announcement in the PIO. She normally can’t make out the words, but keeps one ear on it so that she can tell when the justice is finishing up his or her announcement. When she reaches a stopping point, or when it sounds like the justice is almost finished (two points that are not always the same), she returns to the PIO to wait for the next opinion.