Court upholds life-without-parole sentence for Mississippi man convicted as juvenile

This article was updated on Thursday, April 22, at 7:40 p.m.

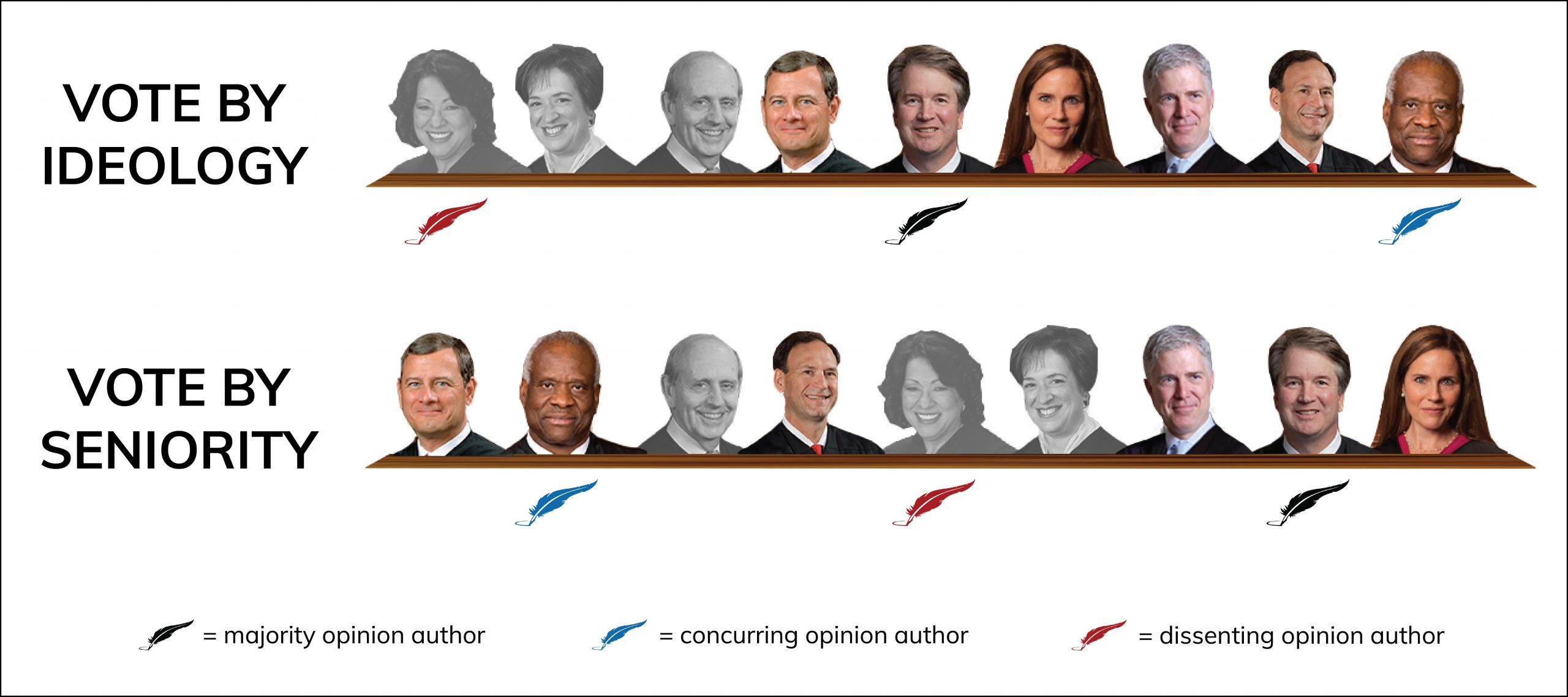

The Supreme Court on Thursday declined to impose new restrictions on the ability of states to sentence juveniles to life without parole, rejecting a challenge from a Mississippi man, Brett Jones, who was convicted of the 2004 stabbing death of his grandfather, a crime committed when Jones was 15. Jones had argued that two recent Supreme Court decisions on mandatory life-without-parole decisions for juveniles the courts 2012 decision in Miller v. Alabama and its 2016 ruling in Montgomery v. Louisiana required the judge who sentenced him to find that he was incapable of rehabilitation before imposing life without parole. By a vote of 6-3 in Jones v. Mississippi, the justices disagreed, holding that it was enough that the judge considered his youth in sentencing him.

In an opinion by Justice Brett Kavanaugh, the majority explained that the Supreme Courts decisions in Miller and Montgomery squarely rejected any requirement that a judge or jury imposing a sentence make a separate finding that the defendant cannot be rehabilitated. All that Miller required, Kavanaugh wrote, was that a sentencer consider youth as a mitigating factor when deciding whether to impose a life-without-parole sentence.

Nothing in Montgomery, Kavanaugh continued, created any additional requirements beyond those outlined in Miller. To the contrary, Kavanaugh explained, the court took up Montgomery only to decide whether the Supreme Courts ruling in Miller, holding that the Eighth Amendment bars mandatory life-without-parole sentences for juvenile offenders, applies retroactively to defendants whose convictions and sentences had already become final. A key assumption in both cases was that discretionary sentencing allows the sentencer to consider the defendants youth, Kavanaugh observed, and thereby helps ensure that that life-without-parole sentences are imposed only in cases where that sentence is appropriate in light of the defendants age. If the Supreme Court in those cases had intended to impose the kind of requirement that Jones says it did, Kavanaugh suggested, the Court easily could have said so and surely would have said so. But it did not, Kavanaugh noted, and in fact declared just the opposite.

Kavanaugh also dismissed Jones alternative argument that, at the very least, the sentencer should be required to provide an explanation for the sentence that includes an implicit finding that the defendant cannot be rehabilitated. Such a requirement, Jones maintained, would ensure that the sentencer actually considers the defendants youth. But the majority was unmoved, positing that it would be all but impossible for a sentencer not to consider the defendants youth. And even the Supreme Courts death-penalty cases dont impose an analogous requirement for mitigating circumstances, Kavanaugh pointed out.

More generally, Kavanaugh emphasized that the courts decision should not be construed as agreement or disagreement with the sentence imposed against Jones. The states, rather than the federal courts, are tasked with making the kinds of broad moral and policy judgments about what an appropriate sentence would be in a case like this one. The Supreme Courts role, Kavanaugh continued, is limited to determining whether the scheme used to sentence Jones complied with the Eighth Amendments ban on cruel and unusual punishment which it did, Kavanaugh reiterated, because the life-without-parole sentence here was not mandatory and the trial judge had discretion to impose a lesser punishment in light of Joness youth. And in any event, Kavanaugh observed, the Supreme Courts ruling is far from the last word on whether Jones will receive relief from his sentence: Among other things, Jones contends that he has maintained a good record in prison and that he is a different person now than he was when he killed his grandfather.

Justice Clarence Thomas agreed with the majority that the Eighth Amendment does not require a separate finding that a juvenile offender cannot be rehabilitated before he can be sentenced to life without parole. But Thomas filed a separate opinion in which he criticized the courts ruling in Montgomery as a demonstrably erroneous decision worthy of outright rejection. In Montgomery, Thomas contended, the court should have acknowledged that its decision in Miller merely created a procedural rule that should not have applied retroactively. But instead, Thomas wrote, Montgomery created a categorical exemption for certain offenders that left the court with two options. It could hold that the Eighth Amendment does indeed impose the kind of requirement that Jones suggested, or it could just acknowledge that Montgomery had no basis in law or the Constitution. But instead, Thomas said, the majority chose a third option: Overrule Montgomery in substance but not in name.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor dissented, in an often sharply worded opinion that was joined by Justices Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan. She accused the majority of distort[ing] Miller and Montgomery beyond recognition. Although Miller does not require a particular procedure to consider the defendants youth or require sentencers to invoke any magic words, the sentencer must determine whether the defendant is one of those rare children whose crimes reflect irreparable corruption, she wrote.

Echoing Thomas opinion, Sotomayor stressed that the majority reaches its conclusion by twist[ing] precedent: It treats Miller as a procedural rule, rather than as a substantive one. But, she added, [a]ny doubts the Court may harbor about the merits of these decisions do not justify overruling them. Under the courts normal practices, she emphasized, it departs from its prior precedent only when there is special justification to do so but the majority offered no such justification in this case. How low, she concluded, this Courts respect for stare decisis has sunk.

Kavanaugh pushed back, stressing that Thursdays decision does not overrule Miller or Montgomery. Miller held that a State may not impose a mandatory life-without-parole sentence on a murderer under 18, Kavanaugh wrote. Todays decision does not disturb that holding. Montgomery later held that Miller applies retroactively to defendants whose direct appeals had already run out by the time the decision was released. Todays decision likewise does not disturb that holding. Instead, Kavanaugh concluded, he and his colleagues in the majority simply have a good-faith disagreement with the dissent over how to interpret those cases.

Thursdays decision was significant in several ways. First and foremost, it may make it easier for states to sentence juvenile offenders to life without the possibility of parole. Second, the 6-3 ruling shows the extent to which the court has shifted to the right since its 5-4 ruling in Miller and its 6-3 ruling in Montgomery. Third, the opinions themselves show that tensions may be running high already behind the scenes at the court, particularly when it comes to the issue of adhering to prior precedent.

This article was originally published at Howe on the Court.

Posted in Merits Cases

Cases: Jones v. Mississippi