Statistics

In Barrett’s first term, conservative majority is dominant but divided

on Jul 2, 2021 at 6:37 pm

At the conclusion of Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s first term, the Supreme Court’s six-justice conservative majority is grappling with its newfound control. A split developing among its members is complicating the conservative revolution some predicted after Barrett’s confirmation last October. But with no anticipation of a Republican-appointed justice retiring anytime soon, and a blockbuster docket next term featuring clashes over abortion and gun rights, the contours of the court’s rightward shift are only just emerging.

These findings come from analysis of our new-and-improved annual Stat Pack. Released today, it contains a wide range of statistics about the 58 oral arguments and 67 merits decisions during the court’s 2020-21 term. (For a full explanation of our dataset, see our introduction.) The Stat Pack is available in full here, and in individual sections at the bottom of this article.

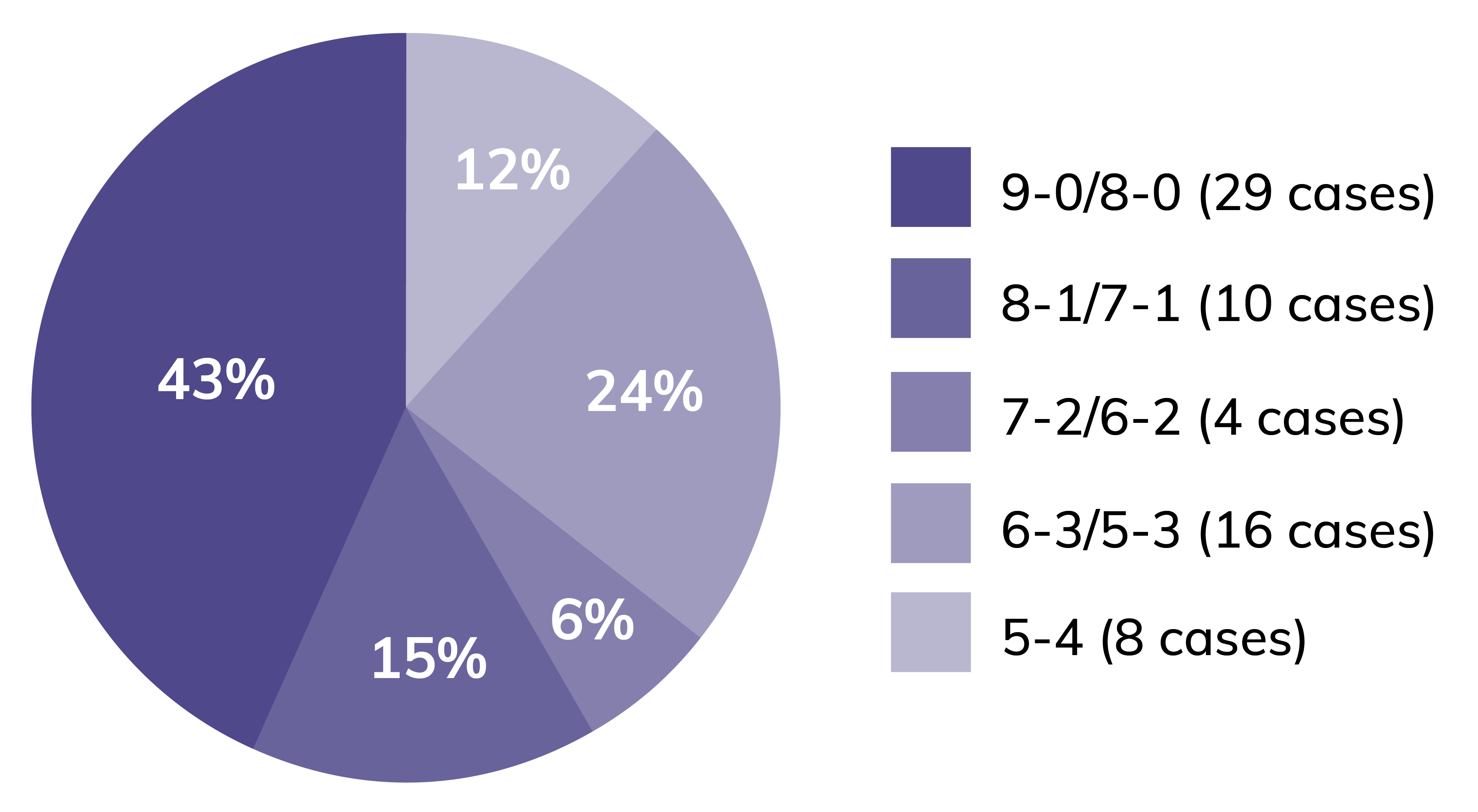

This term, 43% of cases were decided unanimously. That figure is slightly below the 46% average over the past decade, but a few points higher than the past three terms. In contrast, only 12% of cases (8 total) were decided 5-4, a sharp drop-off from the 20% average since John Roberts became chief justice in 2005.

But the number of 5-4 decisions is no longer an accurate measure of the court’s polarization, now that conservative-leaning justices occupy six of the nine seats for the first time during Roberts’ tenure. This term, 10 decisions, or 15% of cases, were completely polarized 6-3 (or 5-3, in one case with Barrett recused) along ideological lines.

Given the controversy surrounding Barrett’s confirmation to replace the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg shortly before the 2020 election, it is fair to ask how often Barrett cast a decisive vote in her first term. If Ginsburg (or a liberal successor appointed by President Joe Biden) had been on the court in place of Barrett, it is likely that the 10 ideologically polarized cases would have reached the same result, just with a 5-4 vote alignment instead of 6-3. But in four other cases, Barrett’s presence did appear to change the outcome from what would have been expected if a Democratic appointee sat in Barrett’s seat and voted alongside the other liberal justices. All four of those cases were decided 5-4 with Barrett in the majority and one conservative justice joining the three liberal justices in dissent. One concerned the constitutionality of appointed administrative patent judges, another tightened the requirements for consumers to file class-action lawsuits, and two granted religious groups exemptions from social-distancing policies in New York and California during the COVID-19 pandemic.

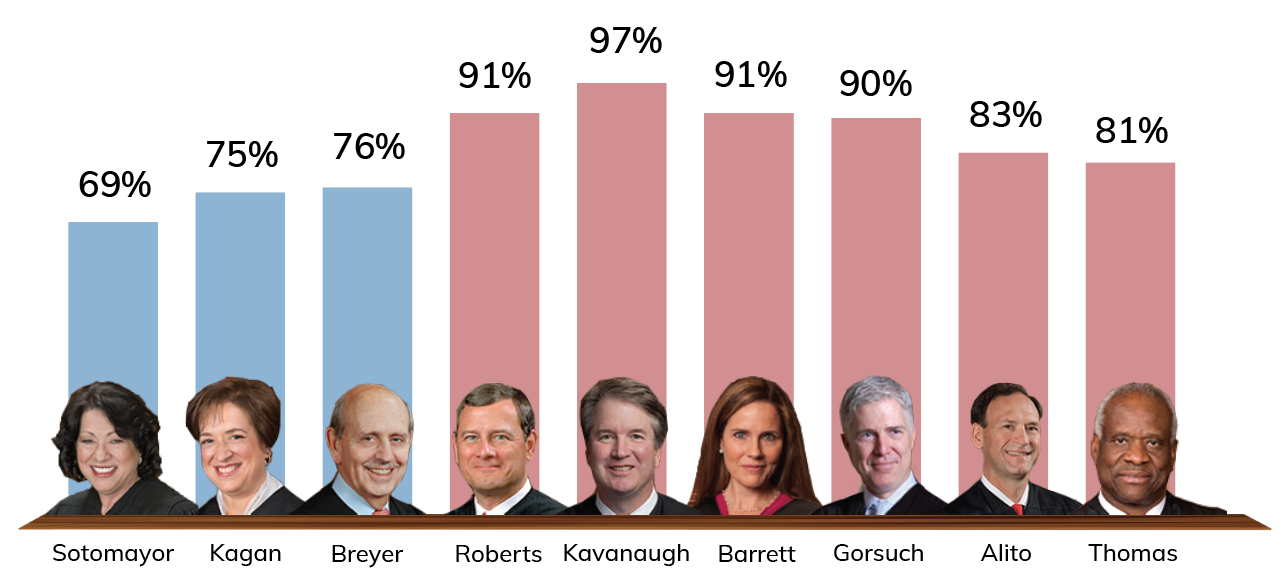

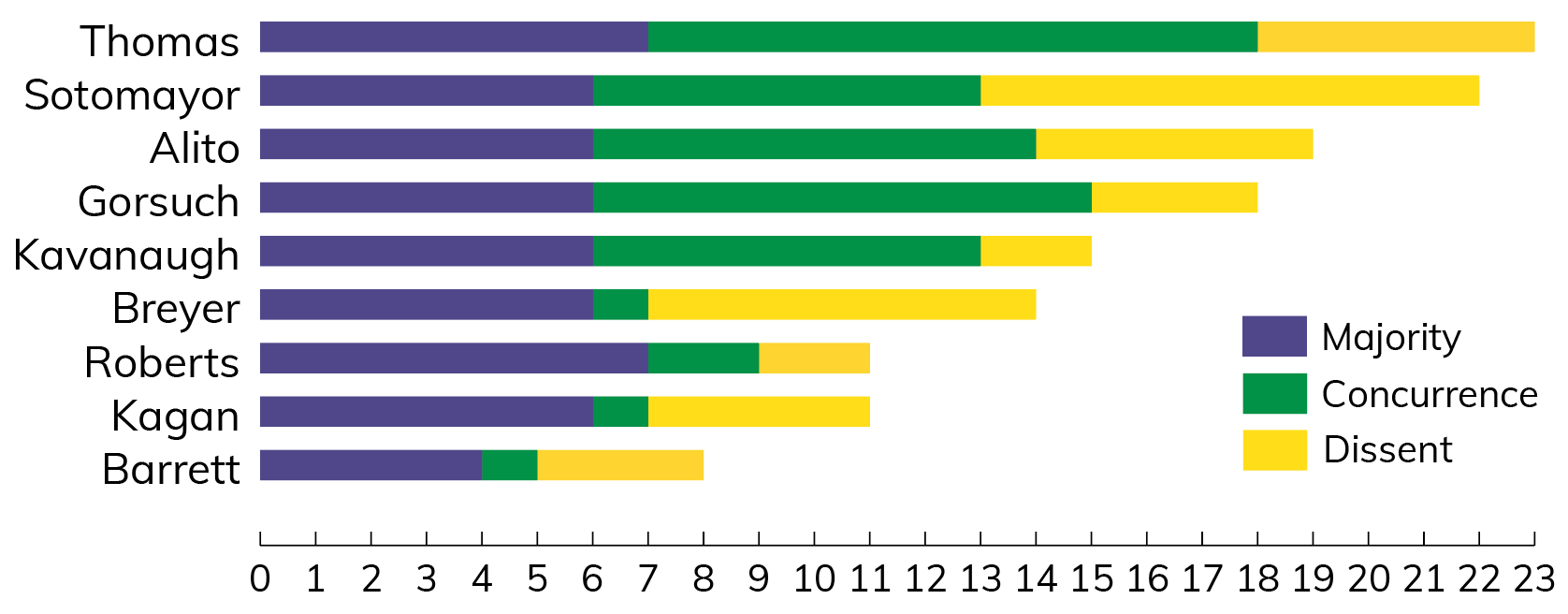

In close cases, the six conservative justices usually get their way. But they do not vote uniformly in every case, and they occasionally have sharp disagreements with one another. We can get a sense of this by looking at the justices’ frequencies of voting in the majority this term.

With Barrett on the court, Justice Brett Kavanaugh has quickly supplanted Roberts as the court’s new ideological median. The prevailing narrative at the end of last term, with Justice Ginsburg still on the bench and the court split 5-4 along ideological lines, was Roberts’ 97% frequency in the majority and evident control over the outcome in close decisions. This term, it was Kavanaugh who found himself in the majority a leading 97% of the time on a more conservative bench, a metric that held steady from the midpoint of the term.

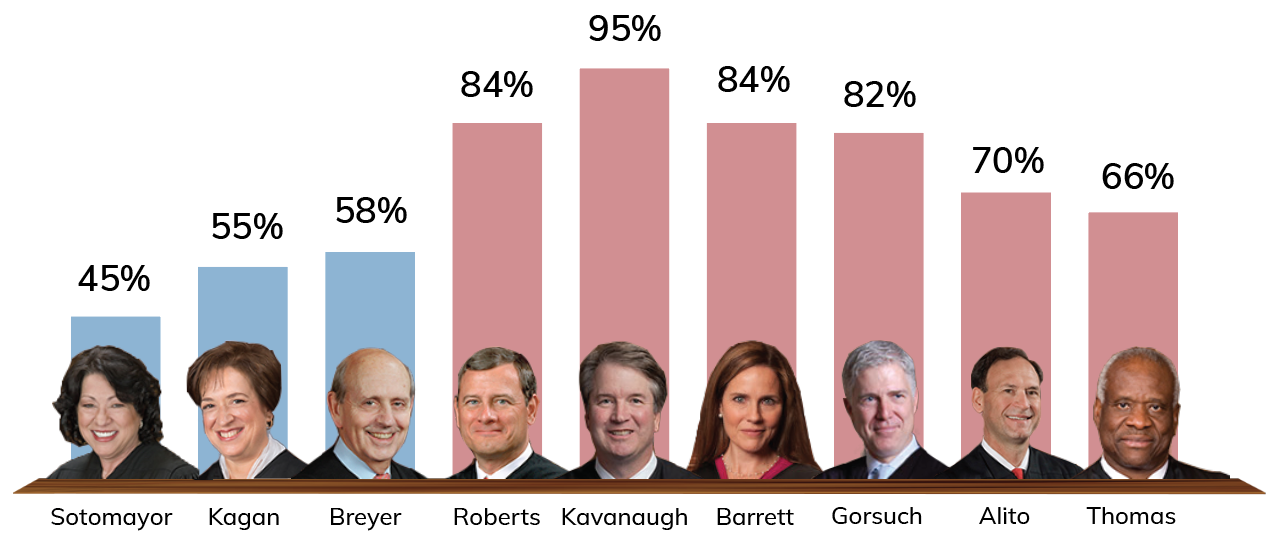

Kavanaugh was also in the majority of an impressive 95% of divided cases (any case not decided 9-0 or 8-0) this term, with Barrett in a distant second place at 84% and the chief two tenths of a point behind her. Since 2012, only one other justice has achieved that 95% mark in divided cases: Roberts, last term.

Looking at divided cases highlights the extent to which the three justices appointed by Democratic presidents have been left out of the majority by the court’s new composition. This term, they notched their lowest (Justices Elena Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor) and second-lowest (Justice Stephen Breyer) rates in the majority in divided cases since 2012. The three were alone in dissent in major rulings this term curbing use of the Voting Rights Act to challenge voting restrictions as racially discriminatory, allowing courts to give life sentences to juveniles without first finding them “permanently incorrigible,” and limiting deportation relief for people in the country without authorization, among others.

Sotomayor, in particular, dissented in more than half of divided cases for the third time in eight years. She penned four of the eight solo dissents issued this term, and she was a frequent author of solo concurrences. As Linda Greenhouse noted for the New York Times, Sotomayor has adopted the role of writing alone to criticize the court when she believes the majority overlooks or misrepresents the factual history and context behind its often textualist opinions. Only Justice Clarence Thomas, the court’s prolific author of solo concurrences, wrote more opinions than Sotomayor this term.

That the six conservative justices enjoyed the highest majority participation, however, does not mean they were always in agreement. In two of the term’s most-followed decisions, Thomas and Justice Samuel Alito (who had the lowest rates in the majority among the six conservatives), as well as Justice Neil Gorsuch, criticized the court for not going far enough.

For the third time in eight years, the court rebuffed a challenge to the Affordable Care Act. Breyer’s technical opinion dismissing the suit was joined without qualification by the three liberal justices as well as by Roberts, Kavanaugh and Barrett. Alito and Gorsuch dissented, scolding the majority for “judicial inventiveness” in yet again upholding the law. Thomas wrote separately to “commend” the dissent but nevertheless joined the majority in its narrow holding.

Religious free exercise drew a sharper divide. By cobbling together a limited ruling that granted a Catholic foster-care service a highly fact-dependent exemption from a Philadelphia policy requiring foster agencies to work with same-sex couples, Roberts managed to avoid an outcome that would have overturned the long-standing precedent in Employment Division v. Smith, which held that religious observers are usually not entitled to exemptions from general laws. Alito, in a scathing, 77-page concurrence joined by Thomas and Gorsuch, criticized the majority for selecting a politically convenient ruling instead of finally disowning that “fundamentally wrong” decision.

Those altercations aside, the court steered clear of many hot-button issues during Barrett’s first term. But two already set for potential blockbuster decisions by next June, and others waiting in the wings, will test how far the new conservative majority is willing to push the court to the right.

This fall, the justices will hear a major abortion case from Mississippi intended to challenge Roe v. Wade and its first significant case on the Second Amendment in over a decade. During the 2019-20 term, Roberts refused to provide a fifth vote to limit abortion access, and there were also signs that he was hesitant to expand gun rights. If Barrett joins Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch and Kavanaugh in voting to do both next term, however, Roberts’ vote might not make a difference.

The justices will also likely decide whether to take up a high-profile challenge to Harvard’s affirmative action policy brought by Asian American students, a choice they temporarily postponed this spring by asking the federal government to weigh in. And the court’s conservative bloc will have another chance to expand religious rights — if only incrementally — in a new case involving public funding for religious education.

Whether Barrett will in fact push the court further to the right on these landmark issues is still an open question. It won’t remain open for long.

Click here to view our complete 2020-21 Stat Pack, or below to view individual sections. This Stat Pack would not have been possible without the help of James Romoser, Angie Gou and Mitchell Jagodinski.