Opinion analysis

In dispute over renewable fuels, justices unravel “extensions” of “exemptions”

on Jun 26, 2021 at 12:51 pm

When Congress says that a firm can apply for an “extension” of an exemption, is a firm that has allowed its exemption to lapse eligible to apply for the “extension?” That is the question that divided the Supreme Court justices Friday in HollyFrontier Cheyenne Refining v. Renewable Fuels Association. Six justices said yes, while three justices said no.

The context in which the question arose was the Renewable Fuels Program that Congress established in 2005. The program is intended to increase the use of renewable fuels such as ethanol. To further that purpose, the statute required refiners to blend renewable fuels with the crude oil they refine. The percent of renewable fuels that refineries must blend increases every year.

Congress was concerned that the blending requirement might have disproportionate adverse effects on small refiners, so it included a statutory exemption applicable to small refiners that lasted until 2011. It also instructed the Department of Energy to study whether the blending requirement had a disproportionate adverse effect on small refiners. If the department found a disproportionate adverse effect, the statute directed the Environmental Protection Agency to consider applications from individual small refiners to extend the exemptions for as long as two years at a time. The department did find a disproportionate adverse effect, and the EPA began to consider whether to grant extensions to small refiners who applied for them.

This case involved three small refiners that had obtained exemptions in the past but had allowed them to lapse. Each refiner applied for and was granted an “extension” of its exemption. The Renewable Fuels Association challenged the validity of the EPA decisions to grant the extensions based on its claim that the three refiners were not eligible to apply for the extensions. The RFA argued that “extension” refers only to a refiner that has continuously obtained an exemption and does not refer to a refiner that has allowed its exemption to lapse. In the opinion of the RFA, such a refiner had no exemption that can be extended.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit agreed with the RFA’s interpretation of “extension” and held that the EPA decisions to grant the extensions were invalid because the three refiners had no exemptions that the EPA could “extend.” In an opinion by Justice Neil Gorsuch, a majority of the Supreme Court disagreed with the 10th Circuit and held that a refiner that has allowed its prior exemption to lapse can apply for and receive an “extension” of its exemption.

The majority began by noting that the statute does not contain a definition of “extension.” The majority concluded that, while “extension” could bear more than one meaning, its “ordinary” meaning includes the situation in which an applicant has allowed its prior exemption to lapse. The majority referred to many sources to support its conclusion, including dictionary definitions, usage of the term in other statutes, usage of the term in ordinary conversation, and the structure of the statute in which the term appears.

The majority recognized that, in some contexts, Congress might use the term to refer only to an extension of an exemption that has been continuously in effect. The majority concluded, however, that there was no reason to believe that Congress intended the term to have any meaning other than its “ordinary” meaning in this context. The majority suggested that Congress could have added qualifying language to give the term the more restrictive meaning urged by the RFA, but Congress did not do so. ,

The majority described arguments that the RFA made in which it urged the court to adopt its preferred interpretation because that interpretation furthered some purpose that the RFA attributed to Congress. The majority declined to consider those arguments because it could only speculate about the reasons why Congress might have used the term to further one of several plausible alternative purposes where Congress did not state the purpose of the power to extend the exemption.

Finally, the majority noted that it had not conferred Chevron deference on the EPA’s interpretation of the statute because the government had not asked it to defer to the agency’s interpretation of the statute.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett dissented in an opinion joined by Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan. The dissenting justices argued that, while the majority attributed to Congress a meaning of “extension” that is “possible,” it did not give the term its “ordinary meaning.” In the view of the dissenting justices, the “ordinary meaning” of “extension” excludes a firm that has allowed its prior exemption to lapse.

In other respects, the dissenting opinion is identical to the majority opinion. It supported its version of the ordinary meaning of the term with a combination of dictionary definitions, usage in other statutes, usage in ordinary conversation, and the structure of the statute in which the term appears. Like the majority, the dissent recognized that Congress might use the term to have the broader meaning the majority attributes to it in some contexts, but the dissent found no evidence that Congress intended it to have any meaning except its “ordinary meaning” in this context. Like the majority, the dissent refused to consider arguments based on claims that Congress intended to use the term to further a particular purpose because it was not willing to speculate about the purpose of the power to extend the exemption.

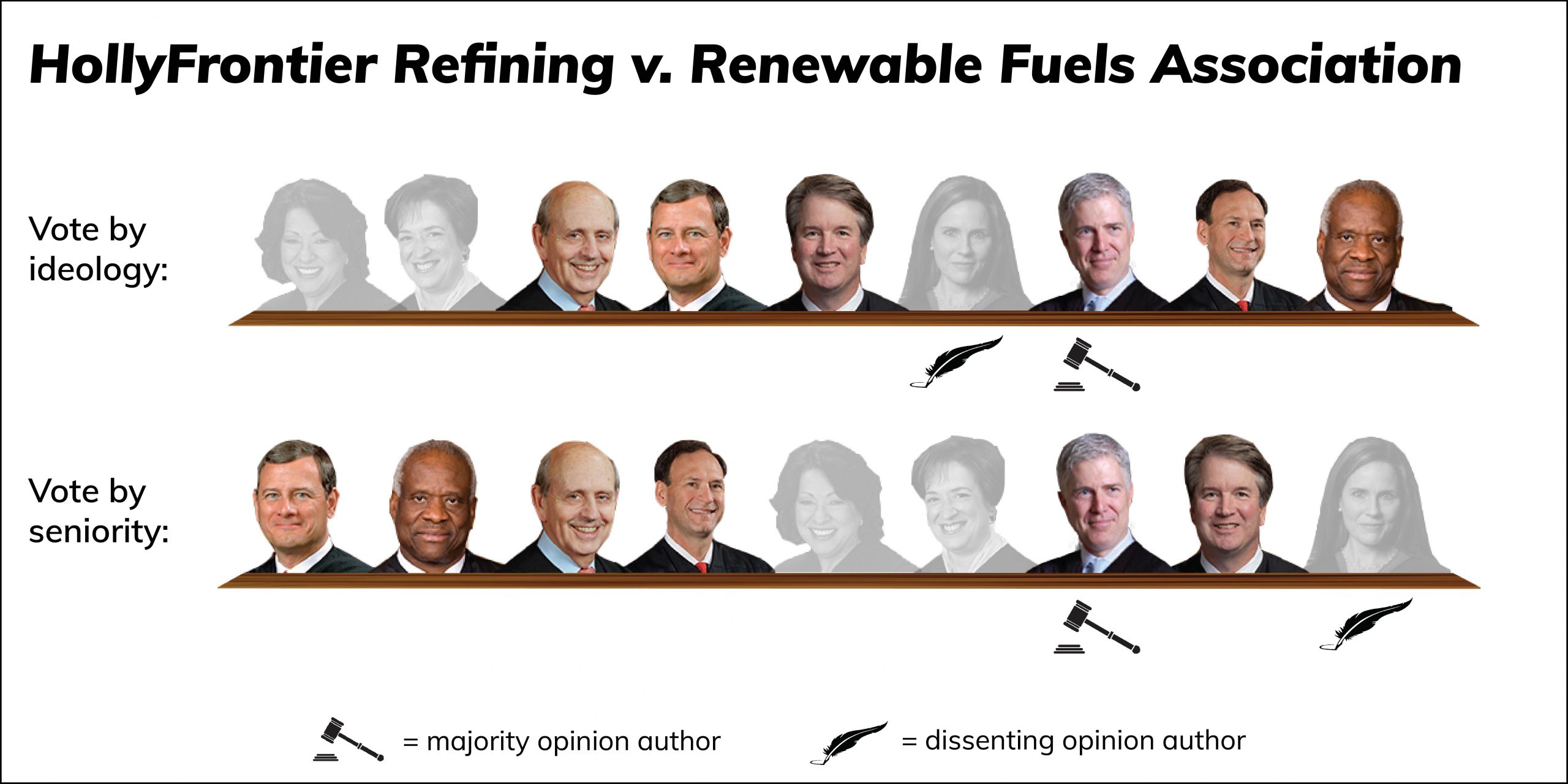

I draw seven inferences from the opinions in this case. First, the court begins its search for the meaning of a term used in a statute by looking for a definition of the term in the statute. Second, absent a statutory definition of the term, the court looks for the “ordinary meaning” of the term. Third, the court looks for evidence of the “ordinary meaning” of the term in dictionaries, usage in other statutes and usage in ordinary conversation. Fourth, the court is willing to consider the structure of the statute in which the term is used and the context in which it is used if but only if there is persuasive evidence that Congress used the term to have a meaning that differs from its ordinary meaning. Fifth, the court is willing to consider arguments based on the alleged purpose for which Congress used a term if but only if there is persuasive evidence that Congress used the term for that purpose. Sixth, the tendency to defer to agency interpretations of ambiguous language in agency-administered statutes that reached its apogee in 1984 when the Court issued its famous Chevron opinion has declined significantly. And seventh, labeling justices as conservative Republicans or liberal Democrats is not helpful in many cases. In this case, the majority consisted of five justices generally viewed as conservative (Gorsuch along with Chief Justice John Roberts, Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito and Brett Kavanaugh) and one justice generally viewed as liberal (Justice Stephen Breyer). The dissent consisted of one conservative (Barrett) joined by two liberals (Sotomayor and Kagan).