Opinion Analysis

Selling cars in a forum state “relates to” a claim involving a car sold elsewhere

on Mar 26, 2021 at 2:02 pm

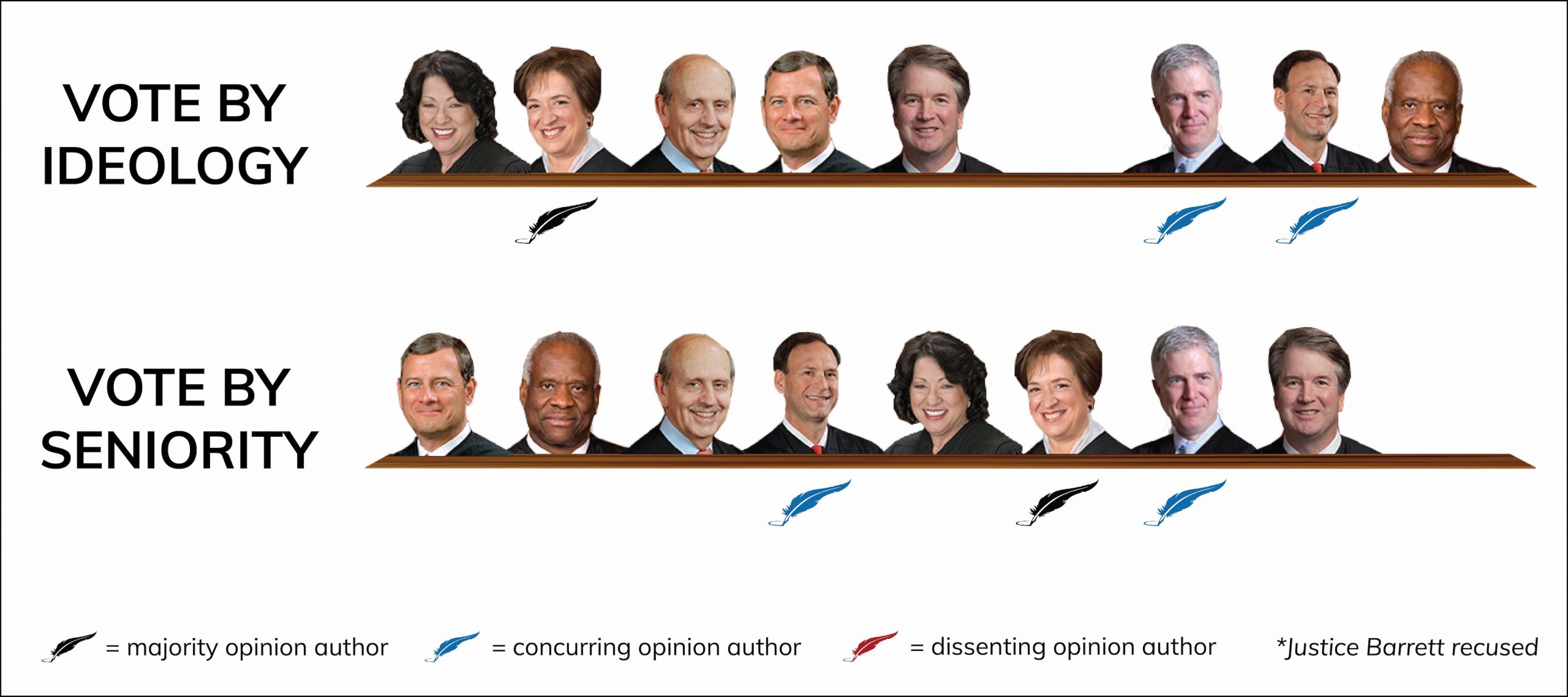

A unanimous Supreme Court in Ford Motor Co. v. Montana Eighth Judicial District Court (consolidated with Ford Motor Co. v. Bandemer) held Thursday that Ford is subject to products-liability suits in Montana and Minnesota arising from car accidents there. Although the cars involved were manufactured and sold outside the states in which the plaintiffs sued, Ford markets and sells identical cars in those states. Justice Elena Kagan’s opinion for the court, joined by four other justices, concluded that Ford’s business activities in the states were close enough to the accidents to support specific personal jurisdiction. Justice Samuel Alito concurred in the judgment, as did Justice Neil Gorsuch, joined by Justice Clarence Thomas. Justice Amy Coney Barrett did not participate in the case, which was argued before she joined the court. The case marks a departure for the Roberts court, following a series of decisions during the past decade ruling in favor of defendants who challenged personal jurisdiction in the states in which they were sued.

Background

Montana Eighth Judicial District arose from a 2015 accident in Montana involving a 1996 Ford Explorer that killed driver Markkaya Jean Gullet. Her estate sued Ford in state court in Montana, alleging design defect, failure to warn and negligence. Gullett’s car was assembled in Kentucky, sold to a dealership in Washington and originally sold to a consumer in Oregon. It went through numerous sales before reaching Gullett in Montana.

Bandemer arose from a 2015 accident in Minnesota involving a 1994 Ford Crown Victoria that injured passenger Adam Bandemer. Bandemer sued Ford in state court in Minnesota, asserting claims for products liability, negligence and breach of warranty. The car involved in the accident was designed in Michigan, assembled in Ontario, Canada, and sold to a dealership in North Dakota. The vehicle was with its fifth owner when registered in Minnesota in 2013.

Kagan’s opinion for the court

Kagan, a former civil procedure professor, wrote for five justices, offering a tour of 40 years of personal-jurisdiction jurisprudence. “Specific jurisdiction” requires two things: Purposeful availment and relatedness. The defendant must “purposefully avail” itself of the privilege of conducting activities in the forum state, such as by exploiting a market through sales, marketing and advertising. Relatedness requires that the plaintiffs’ claims “arise out of or relate to” the defendant’s contacts with the forum state; Kagan explained that element as requiring “an affiliation between the forum and the underlying controversy, principally, [an] activity or occurrence that takes place in the forum State and is therefore subject to the State’s regulation.” These rules seek to treat defendants fairly and to protect “interstate federalism,” a form of reciprocity between a defendant and a state. The rules also give defendants “fair warning” of when their conduct may subject them to the jurisdiction of a state; that warning allows defendants to structure their primary conduct to avoid or minimize exposure to the courts of a given state.

Ford conceded that it does substantial business in Montana and Minnesota, seeking to serve the market for automobiles and related products in both states. In more “doctrinal” terms, Kagan wrote, Ford purposefully avails itself of the privilege of conducting activities in both states. Ford argued that its in-state activities did not sufficiently connect to the suit, however, because there was no causal connection between its in-state activities and the accidents at issue. Kagan framed Ford’s argument as locating specific jurisdiction where Ford designed, manufactured or sold the vehicle, regardless of the place of the accident and injury.

But Kagan, joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Brett Kavanaugh, rejected Ford’s “causation-only approach” as not grounded in precedent. The most common formulation of the relatedness rule is written in the disjunctive — “arise out of or relate to.” While the former suggests causation, the latter “contemplates that some relationships will support jurisdiction without a causal showing.” Kagan suggests that the facts of Ford were addressed in dicta in World Wide Volkswagen Corp v. Woodson. Although that 1980 decision held that an Oklahoma state court lacked jurisdiction over a New York-based car dealer and distributor, the court contrasted the foreign manufacturer and nationwide importer. Because their business deliberately extended into Oklahoma, that state’s courts could have held the companies accountable there, “even though the vehicles had been designed and made overseas and sold in New York.” The court later offered these facts as the paradigm of specific jurisdiction — a resident of a state, injured in his home state in an accident in a defendant-manufactured vehicle. Ford brings that paradigm to life.

The state courts’ jurisdiction over Ford became obvious from Ford’s contacts in the forum states. Ford urges forum residents to purchase its vehicles, including the models involved in these accidents, Kagan wrote, “by every means imaginable.” The company’s cars are available for sale, new or used, in numerous dealerships. And it maintains “ongoing connections” to owners through maintenance, repairs and sale of replacement parts. Ford has “systematically served a market” in these states for the type of vehicles the plaintiffs allege to be defective. That creates a “strong ‘relationship among the defendant, the forum, and the litigation,’ the ‘essential foundations of specific jurisdiction’” Ford argued that the plaintiffs’ claims would be the same if Ford did nothing in the forum states, because it had nothing to do with these cars entering those states. But Kagan rejected that assumption, because the plaintiffs may not even have purchased Ford cars if not for the company’s extensive activities in their home states.

Allowing jurisdiction also treats Ford fairly, Kagan reasoned. Ford enjoys the benefits and protections of the laws of these states for its business activities; the states’ enforcement of Ford’s obligations that its cars be safe is neither undue nor surprising.

The court distinguished two recent decisions — Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. v. Superior Court of California and Walden v. Fiore. In Bristol-Meyers, the plaintiffs were not residents of the forum state and had not suffered injury in the forum state; on the other hand, the Ford plaintiffs are citizens of the forum states and suffered their injuries there. In Walden, the court found a lack of jurisdiction because only the plaintiff, not the defendant, had any contact with the forum; the defendant had not purposefully availed himself of the privilege of conducting activities in the forum. Walden never considered a connection between the defendant’s in-state activity and the plaintiff’s claim, because the defendant engaged in no in-state activity. This contrasts with Ford’s “veritable truckload” of admitted contacts, requiring the court to ask the next question (unasked in Walden) of the link between those contacts and the plaintiffs’ claims.

Alito, concurring in the judgment

Alito concurred in the judgment. He agreed with the “main thrust” of the majority that the defendant’s forum contacts need not be the but-for cause of the plaintiffs’ tort injury. But Alito rejected as unnecessary and unwise the court’s innovative gloss of a distinction between “arise out of” and “relate to” in defining the required connection between contacts and the claim. The terms overlap, Alito said, creating a single standard requiring some causal link, although not the strict causal relationship Ford demands. Alito nevertheless found a sufficient link because the cars would not have been purchased and used in the forum states if Ford were an unknown brand that did not advertise, sell or repair vehicles there.

Gorsuch, concurring in the judgment

Gorsuch, joined by Thomas, also concurred in the judgment. Gorsuch questioned the entire framework of International Shoe Co. v. Washington – the “canonical” due process decision on personal jurisdiction – which established a dichotomy between purposeful availment and relatedness. “The real struggle here,” Gorsuch wrote at the end of his 11-page concurrence, “isn’t with settling on the right outcome in these cases, but with making sense of our personal jurisdiction jurisprudence and International Shoe’s increasingly doubtful dichotomy.” He urged future litigants “to address the challenges posed by our changing economy in light of the Constitution’s text and the lessons of history.”