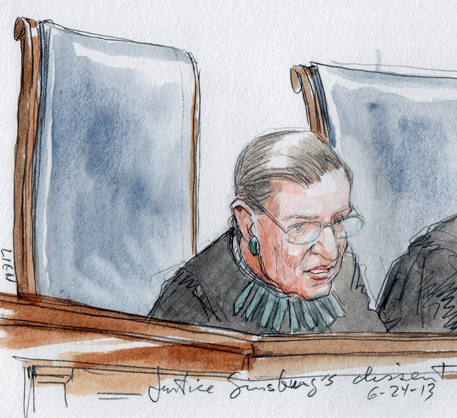

Symposium: Ginsburg, the death penalty and strategic gradualism

on Oct 5, 2020 at 9:43 am

This article is part of a symposium on the jurisprudence of the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Jeffrey L. Kirchmeier is a professor of law at CUNY Law School and author of Imprisoned by the Past: Warren McCleskey, Race, and the American Death Penalty.

When Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was appointed to the Supreme Court in 1993, she had never ruled in a death penalty case. She brought to the court her experience both as an attorney protecting oppressed groups and as a court of appeals judge who embraced judicial moderation. During the subsequent years, her support for individual rights and her judicial moderation informed her approach to capital punishment amid growing societal concerns about the unfairness of the death penalty system.

In both public statements and her votes, Ginsburg recognized problems with the implementation of the death penalty. For example, during a lecture in Maryland in 2001, she discussed poor legal representation of capital defendants and stated that she was “glad to see” Maryland pass an execution moratorium bill. In 2011, she told law students that she hoped the court one day would hold that “the death penalty could not be administered with an even hand.” Despite those concerns, Ginsburg, taking a methodical approach, never wrote an opinion declaring the death penalty unconstitutional in all cases.

Some justices have taken the broader position. Justices Thurgood Marshall and William Brennan rejected the return of the death penalty in the 1970s by reasoning that capital punishment violates the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution. Marshall and Brennan dissented in every case upholding a capital sentence through the rest of their careers.

Other justices later took that position near or at the end of their judicial careers. In February 1994, during Ginsburg’s first term on the court, Justice Harry Blackmun wrote a dissenting opinion concluding that the death penalty is unconstitutional. Around that same time, former Justice Lewis Powell revealed he regretted his votes upholding the death penalty. Similarly, and also during Ginsburg’s time on the court, Justice John Paul Stevens wrote in 2008 that the death penalty is “patently excessive and cruel and unusual punishment violative of the Eighth Amendment.”

Unlike those justices, Ginsburg was not on the Supreme Court for the landmark death penalty decisions upholding the modern death penalty in the 1970s and 1980s, such as Gregg v. Georgia and McCleskey v. Kemp. As a law professor, she co-authored an amicus brief for the American Civil Liberties Union in the important 1977 case on capital punishment and sexual assault, Coker v. Georgia. But her judicial experience with the death penalty largely spanned a time of declining executions, and that backdrop may have helped guide her to a more gradual approach of working with her colleagues at chipping away at capital punishment rather than sweeping broadly.

Her approach to capital punishment cases grew from a thoughtful strategic decision. She believed she could be more influential by participating directly in the court’s decisions analyzing capital punishment rather than by taking a broad position that the death penalty always violated the Constitution. Although some criticized her approach, her careful analysis drew respect from her colleagues, with justices on the other side of a case sometimes acknowledging the logic of her reasoning.

So, even though Ginsburg declared to an audience in 2017, “If I were queen, there would be no death penalty,” she approached the death penalty not as a monarch, but as a jurist, carefully carving away with a scalpel to expose the problems she saw with America’s system of executing people. She relied on precedent to try to ensure capital sentencing followed the constitutional demands that procedures be fair and reliable, while enforcing the court’s proclamations that death sentences differ from other punishments. Her approach to capital punishment was similar to her approach to other constitutional criminal procedure cases, which as illustrating a “preference for narrow rulings that adhere closely to precedent and that avoid grand pronouncements.”

During Ginsburg’s career, she did sometimes vote to uphold death sentences. But generally her written opinions and votes tended to be on the side of the condemned. Her majority decisions included Shafer v. South Carolina, involving jury instructions on the alternative of life without parole sentences, and Ring v. Arizona, in which the court held that the Sixth Amendment right to a jury required juries, not judges, to determine “aggravating factors” that would justify a death sentence.

In capital cases in which she did not write an opinion, Ginsburg’s vote was often crucial. During this century, she voted in the majority of every 5-4 Supreme Court decision in favor of capital defendants. She cast important votes striking capital punishment for people with intellectual disabilities, for juveniles and for defendants in cases in which nobody was killed.

Ginsburg also played a key role in lower-profile cases, often voting to grant stays of executions or deny applications to vacate stays. In recent years since the Death Penalty Information Center began keeping track of the statistic, no capital defendant received a stay of execution without her vote.

Despite her careful jurisprudence, Ginsburg saw broader problems with the death penalty, including limits on habeas corpus, failures to protect innocent defendants and unequal treatment based on race and other factors. She brought to her capital punishment jurisprudence her compassion for people tossed aside by society. For instance, she wrote poignantly of the risk of pain and suffering during executions in her dissenting opinion in Baze v. Rees.

Toward the end of her life, Ginsburg’s long experience led her further. Although she never wrote a sweeping opinion concluding that the death penalty in all cases is unconstitutional, her colleague Justice Stephen Breyer in 2015 wrote a dissenting opinion in Glossip v. Gross, asking that the court request briefing on “whether the death penalty violates the Constitution.” The long dissent documented numerous reasons it is “highly likely that the death penalty violates the Eighth Amendment.” No other justice joined the dissent and the call to reassess the constitutionality of the death penalty … except for Ginsburg. And in July of this year, she again joined Breyer in questioning the constitutionality of the death penalty.

While we may only speculate what would have happened had the court taken up the issue, through Ginsburg’s careful and reasoned approach in her death penalty jurisprudence, she provided a bold voice for moderating and challenging the American system of capital punishment. Her votes and analysis created an important record that remains, even as the sudden absence of her voice protecting the powerless has left a gaping hole on the court. All who care about fairness, justice and equality will miss her.