Clerking for Justice Ginsburg was a gift beyond measure

on Sep 22, 2020 at 2:21 pm

This tribute is part of a series on the life and work of the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Justice Goodwin Liu is an associate justice of the California Supreme Court. He clerked for Ginsburg during the 2000-01 term.

I’m often asked what it was like to clerk for Justice Ginsburg.

I first met Justice Ginsburg at my clerkship interview. I was excited, and nervous, so I asked a couple of former clerks for advice. They said they loved working with her, and they noted that she spoke softly and often paused between sentences, so I should be careful not to interrupt her. Over the years, I got used to her pace of conversation, but at the interview, I let so much time pass before responding to things she said that she must have thought I was waiting for translation.

The fact is that Justice Ginsburg was always very careful in choosing her words, written or spoken. If we were as careful as she was, we might slow down and pause more often too.

Ten minutes into the interview, she offered me the clerkship. I was so thrilled that the rest of the conversation was a blur. I do remember that she had read my writing sample, an obscure law review article titled “Social Security and the Treatment of Marriage.” She knew this topic inside and out because one of her favorite cases as a litigator was Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld, in which the Supreme Court struck down a Social Security provision that allowed widows but not widowers to collect survivor benefits. We found common ground in critiquing gendered breadwinning and caregiving roles, and now as a parent balancing work and home life, I often draw inspiration from the example that she and her husband Marty set for all of us.

During my year at the court, the clerks had a regular basketball game on Tuesdays and Thursdays on the top floor of the building, “the highest court in the land.” During one game, I collided with a very genial and very tall Scalia clerk, and I badly sprained my ankle. As I lay in bed the next morning, the first person to call to check on me was Justice Ginsburg — and as we know, she was not a morning person. She was incredibly thoughtful that way.

Another memory is the time Justice Ginsburg took me to the opera. Marty was unavailable, and I drew the lucky straw in our chambers. That evening I met her at her apartment, and we walked together to the Kennedy Center and back again afterward. This was well before she became a global celebrity. As we walked, she talked about her neighborhood routines and pointed out some of her favorite shops and her dry cleaner. If she had a security detail that night, I didn’t see it. In so many ways, she was an extraordinary person, but I was glad to see how she was ordinary too.

Justice Ginsburg was a meticulous writer and editor. One day I went into her office to look at a case file. The file contained a bench memo written by a clerk, and I noticed that the memo had edits, including missing commas and various typos, marked by Justice Ginsburg in faint pencil. Such editing was apparently her regular practice when she read our memos, but it was a surprise to me because she never returned those memos to us. It was just her way of demanding perfection in whatever writing was before her eyes. My co-clerks and I were mortified at the thought that we had given her memos with such errors. And it taught me to be vigilant because every error, no matter how small, is a speed bump on the road of one’s argument or analysis.

I clerked in the 2000 term, the year of Bush v. Gore. Throughout that controversy, Justice Ginsburg was a paragon of even temperament and collegiality. She analyzed the issues carefully and never lost her cool. Having now, as a judge myself, experienced disagreement over matters far less consequential than the presidency of the United States, I have even more regard for how she navigated that challenging period.

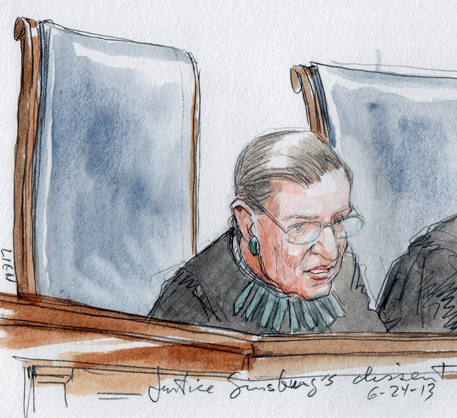

Bush v. Gore was perhaps the beginning of Justice Ginsburg’s public identity as a “great dissenter.” In hindsight, this role was hardly foreordained. But she was resolute on matters of principle, and she grew into the role. Her notable dissents — Ledbetter, Shelby County, Epic Systems, Hobby Lobby, Carhart, Wal-Mart and others — are studies in judicial craft. She was masterful at framing issues and using language. She knew what to say and what to leave unsaid. Her writing was never toxic, but powerful enough to sting.

Although dissents are sometimes seen as acts of futility, her dissents came to be viewed as acts of resistance, especially when she dissented against an all-male majority. She inspired countless women and girls to believe their voice matters and to have the courage to use it.

I clerked for Justice Ginsburg one year after she was diagnosed with colon cancer. During the clerkship, she underwent several rounds of treatment. None of it could have been pleasant, but she never missed oral argument and finished all her work on time. If she was ever anxious or in pain, she never let it show.

She survived that cancer and, despite subsequent cancer diagnoses, kept surviving and thriving. Over the years, there were multiple cycles of a health scare followed by intense media speculation, and then her successful recovery and return to work. Frankly I became a bit desensitized to worries about her health. She told me that one time, when she was a little slow in getting up from her seat at the end of oral argument, the press inquired whether she was ill. Not at all, she said — the reason was that she had kicked off her shoes during argument and was having difficulty putting one of them back on!

She appeared to be in good health all the way to this year. The last time I saw her was in February at an intimate dinner hosted by Judge David Tatel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit (for whom I also clerked) and his wife, Edie. D.C. Circuit Chief Judge Sri Srinivasan was also in attendance. It was a warm occasion. Justice Ginsburg had a special fondness for the Tatels and delighted in the fact that Judge Tatel succeeded her on the D.C. Circuit. She also had evident affection for Chief Judge Srinivasan, whom she was planning to take to the opera until the pandemic hit. She was in good spirits and looking ahead. When she arrived that evening, she said her doctor had limited her to one glass of wine. By the end of dinner, she was on her third.

It turns out that one can beat pancreatic cancer for only so long. Yet she never stopped working and never stopped fighting until the very end. She understood that it is one thing to have a disease, but quite another for the disease to have you.

Justice Ginsburg dedicated her life to making America better, and she gave it her all. The massive outpouring of grief throughout the nation is truly extraordinary. The law books contain only part of her powerful legacy. The rest resides in the hearts and minds of the millions who love and admire this exceptional woman.

Zikhronah livrakha. May her memory be a blessing.