Ask the author: The evasive virtues and Supreme Court confirmation hearings

on Sep 15, 2020 at 10:32 am

The following is a series of questions posed by Ronald Collins to Ilya Shapiro concerning his forthcoming book, Supreme Disorder: Judicial Nominations and the Politics of America’s Highest Court (Regnery Gateway, 2020).

Ilya Shapiro is the director of the Robert A. Levy Center for Constitutional Studies at the Cato Institute and publisher of the Cato Supreme Court Review. He is the co‐author of Religious Liberties for Corporations? Hobby Lobby, the Affordable Care Act, and the Constitution (2014). Shapiro has testified many times before Congress and state legislatures and has filed more than 300 amicus briefs in the Supreme Court. He clerked for Judge E. Grady Jolly on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit.

Welcome, Ilya, and thank you for taking the time to participate in this question-and-answer exchange for our readers. And congratulations on the publication of your latest book.

* * *

Question: What prompted you to write this book, and why now?

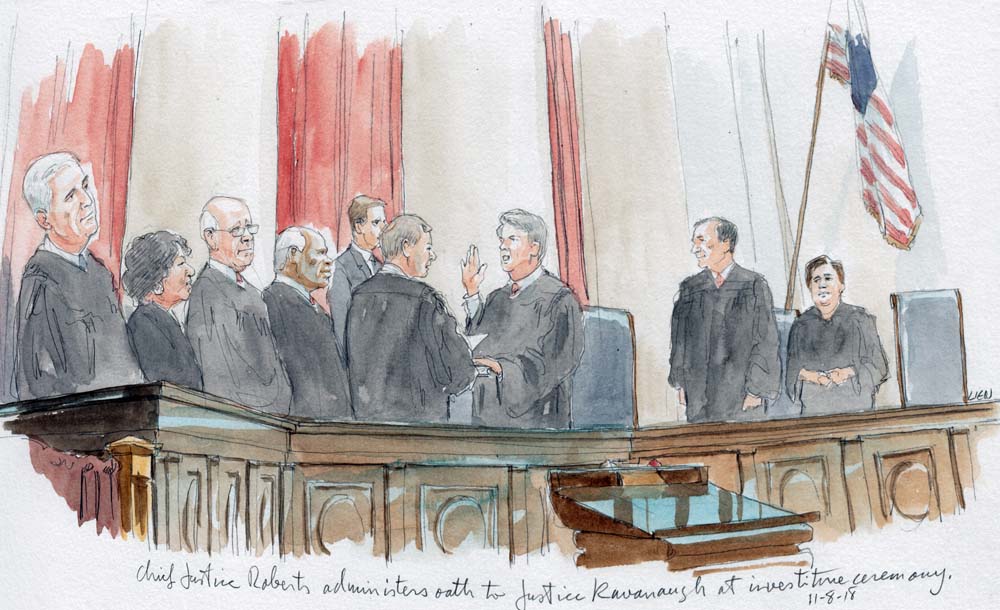

Shapiro: I’ve been a “professional” court-watcher for over a decade, and even before that was riveted by Supreme Court confirmation hearings whenever they came up. I recall once walking into a law firm partner’s office for a job interview and he had Samuel Alito’s hearings on TV; we watched for half an hour before getting on with the interview (I got the offer). I even own a complete bound set of volumes from the Robert Bork hearings — picked them up from a library that was discarding these treasures. But anyway, the battle over Brett Kavanaugh showed that the court is now part of the same toxic cloud that envelops all of the nation’s public discourse. I wanted to dive into why that is and whether it can be fixed. And after the central role the vacancy in Justice Antonin Scalia’s seat played in the 2016 election, I knew I had to get this out before the 2020 election.

Question: How would you summarize the thesis of your book?

Shapiro: Politics has always been part of judicial nominations, but we feel something is now different. The confirmation process hasn’t somehow changed beyond the Framers’ recognition, and political rhetoric was as nasty in 1820 as it is in 2020. Even blocking or not taking up nominees, as happened to Merrick Garland, is hardly novel. But all these things are symptoms of a larger phenomenon: As government has grown, so have the laws that courts interpret, and their reach over more of our lives. Senatorial brinksmanship is symptomatic of a problem that began long before Kavanaugh, Garland, Clarence Thomas or Bork: the courts’ aiding and abetting the expansion of federal power, and then shifting that power away from the people’s representatives and toward the executive branch.

As courts play a greater role, of course nominations are going to be more fraught — especially when divergent interpretive theories map onto partisan preferences at a time when our parties are more ideologically sorted than since at least the Civil War. But in the end, all the “reform” discussion boils down to re-arranging deck chairs on the Titanic, which isn’t the appointment process, but the ship of state. The basic problem we face is the politicization not of the process but of the product. The only way confirmations will be detoxified is for the court to rebalance our constitutional order by returning improperly amassed power to the states, while forcing Congress to legislate on truly national issues.

Question: What was one of the most important discoveries you made while researching this book?

Shapiro: American history is long enough that there’s little new under the sun. We think we’re at a period of heightened opposition to potential justices, but of 163 nominations formally sent to the Senate, only 126 have been confirmed, a success rate of just 77%. Much of this can be explained by party control of the Senate and White House. Historically, the Senate has confirmed fewer than 60% of Supreme Court nominees under divided government, as compared to about 90% under unified government. And nearly half the presidents have had at least one unsuccessful nomination, starting with George Washington and running all the way through George W. Bush and Barack Obama. Even qualitatively, I would put the Louis Brandeis nomination in 1916 ahead of modern battles in terms of controversy — and it took the longest time — even if he was ultimately confirmed by a more comfortable margin.

Question: There is a notable element of legal realism in your book, especially in the chapter titled “What Have We Learned?” All seven lessons you set forth there suggest there is no way out of the politicization of the judicial confirmation process. Is that your view? Might the real problem be not so much the confirmation process but the modern use of federal judicial review?

Shapiro: That’s exactly right. We have severe — and sincere — disagreements over the substance of constitutional law and methods for interpreting statutes, ones that can’t simply be waved away by invoking “norms” or “courtesy.” What courts decide really matters, so who decides also matters. I don’t think the problem is with “judicial review” as such — the Supreme Court really doesn’t invalidate many laws, and the Roberts court overturns precedents at a significantly lower rate than its predecessors — but it’s absolutely appropriate for senators (and voters) to debate the theories that potential nominees would apply. Given a finite number of seats, political clashes are unavoidable.

Question: The inside flap of your book states that the judicial-appointments process has been adversely affected by “decades of constitutional corruption.” Tell us about the nature of that corruption and when it began.

Shapiro: I would trace the corruption to what legal scholars call the “constitutional revolution of 1937,” but that goes beyond that year’s key cases of West Coast Hotel v. Parrish, Helvering v. Davis, Steward Machine Co. v. Davis, and NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin, as well as the previous year’s Butler v. United States, the next year’s United States v. Carolene Products, and the infamous Wickard v. Filburn (1942).

In 1935, President Franklin Roosevelt wrote to the chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee: “I hope your committee will not permit doubts as to constitutionality, however reasonable, to block the suggested legislation.” Eventually, the court rendered constitutional limits on federal power unenforceable and made certain rights more equal than others. After the “switch in time that saved nine,” when the court began approving grandiose legislation it had previously rejected, no federal laws would be set aside as going beyond congressional power until 1995. But even the 1930s and ’40s don’t tell the whole origin story: If the Slaughterhouse Cases (1873) hadn’t eviscerated the 14th Amendment’s privileges or immunities clause, for example, we wouldn’t have the warped conception of unenumerated rights — “penumbras and emanations” and the like — that’s also central to confirmation battles.

Question: You argue that the court “has let both the legislative and executive branches swell beyond their constitutionally authorized powers.” Can you give us an example of this under the Roberts court?

Shapiro: The most obvious example is National Federation of Independent Businesses v. Sebelius (2012), in which Chief Justice John Roberts transmogrified Obamacare’s individual mandate penalty into a tax. It’s certainly gratifying to those of us in that fight that a majority of justices rejected the government’s assertion of power to compel commerce in order to regulate it. But justifying a mandate with an accompanying penalty for noncompliance under the taxing power doesn’t rehabilitate the statute’s abuses. It merely created a “unicorn tax,” a creature of no known constitutional provenance that will never be seen again. And by letting the law survive in such a dubious way, Roberts undermined the trust people have that courts are impartial arbiters, not political actors.

Question: You talk a lot about the administrative state (or, as you sometimes refer to it, a “faceless bureaucracy” or “alphabet agencies”). How does this relate to the confirmation process as you understand it?

Shapiro: The collection of ever-expanding powers in the administrative state has transferred decision-making authority to the courts. Indeed, the imbalance between the executive branch and Congress — especially the latter’s abdication of its leading constitutional role by delegating what would otherwise be legislative responsibilities — has forced the Supreme Court to decide complex policy disputes. What’s supposed to be the most democratically accountable branch has been avoiding hard choices since long before the current polarization.

Gridlock is a feature of a legislative process that’s meant to be hard, but it is compounded of late by citizens of all political views being fed up with a situation where nothing changes regardless of which party is elected. Washington has become a perpetual-motion machine and the courts are the only actors able to throw in an occasional monkey wrench. That’s why people are concerned about the views of judicial nominees — and why there are more protests outside the Supreme Court than Congress.

Question: During his 1987 confirmation hearings in the Senate, Bork violated every norm of modernity in word, demeanor, appearance and tactic. He did not feign meekness or prevaricate. He did not fully disavow his former views. He did not kowtow to the whims of his senatorial adversaries or play to the press. He remained conceited and confident throughout. And all of this in the face of a voluminous record of speeches, scholarly writings and judicial opinions certain to invite opposition. In short, Bork did not pretend to be the man he was not. The result: 58 senators voted against his confirmation and 42 for. As Judge Richard Posner viewed it: “He had posed as supremely apolitical, as just letting the chips fall where they may.”

Would you characterize Bork’s strategy as principled or foolhardy?

Shapiro: Both. A nominee has to understand that his or her only goal is to get confirmed, while Bork seemed to think he was there to pass an oral exam. The Justice Department would’ve coached him better, but this nominee didn’t want coaching, blowing off so-called “murder board” sessions. As Senator Paul Simon (D-Ill.) put it: “Bork tended to want to score debate points, rather than appeal to the Committee for votes.” But the White House also erred in its strategy, which was to portray Bork as neither a conservative nor a liberal — much like the “swing justice” he was nominated to replace, Lewis Powell. The demagogic attacks from Sen. Ted Kennedy (D-Mass.) and various left-wing groups caught the administration on its back foot.

Question: Building on the last question, and given where we are, it seems that the formula for any nominee to the Supreme Court who hopes to be confirmed is simple. Be evasive yet engaging. Let long-winded senators steal your time. Appear sophisticated, yet avoid controversy or complexity. Deliver soundbites instead of professorial gradations. And be sure to appear groomed, well-suited and TV-friendly.

Will we ever see an end to this in our lifetimes? If so, how? If not, why shouldn’t senators be even bolder in countering such “Kabuki dances,” as you label them?

Shapiro: Indeed, successful nominees talk a lot without saying much. Ruth Bader Ginsburg refined that tactic into a “pincer movement,” refusing to comment on specific fact patterns because they might come before the court, and then refusing to discuss general principles because “a judge could deal in specifics only.”

Around the same time, Elena Kagan wrote a law review article criticizing judicial nominees for being too cagey. But when she sat in the hot seat herself, she realized why they did so: There’s no incentive to be more forthright and thus open yourself to attack, and every incentive just to demonstrate deep knowledge and an easygoing manner.

So no, I don’t see a change possible, particularly when senators themselves have an incentive to collect clips of gotcha questioning for reelection or presidential campaigns, as we saw with Sens. Cory Booker (D-N.J.) and Kamala Harris (D-Calif.) at the Kavanaugh hearings. I mean, Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Mo.) can declare that he won’t vote for anyone who doesn’t explicitly come out against Roe v. Wade, but that seems like shooting yourself in the foot barring a huge Republican majority that can afford to lose moderate votes.

Question: Assume that the Democrats win the 2020 election, but in late November, one of the liberal members of the court steps down, and President Donald Trump promptly nominates a staunch conservative to replace them. Against the backdrop of the 2016 nomination of Garland, which you discuss in detail, what would you urge Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell to do?

Shapiro: As I discuss in my book, this is all about raw politics. The last time the Senate confirmed a nominee from a president of the opposing party to a high-court vacancy arising during a presidential election year was 1888 — that’s the Garland situation — but now the Senate and president are politically aligned.

Moreover, vacancies have arisen 29 times in presidential election years, during the administrations of 22 of the 44 presidents preceding the current one, and those presidents made nominations all 29 times. Nine times presidents made nominations after the election, in the Senate’s lame-duck session, and all but one of those was confirmed, including several after the nominating president lost the election. (Chief Justice John Marshall was one.)

So again, this is purely about politics, not law or precedent, and what McConnell will have to consider are such things as whether confirming someone would hurt the court’s legitimacy and ultimately whether the Democrats would pack the court in response. Of course, some on the left claim that all of the Republican-appointed justices are illegitimate for one reason or another, and McConnell can’t control the Democrats, who may add justices regardless. Judicial nominations are a winning issue for Republicans, so I say go for it.

Question: You seem cautiously amenable to the idea of term limits for the justices. What is your thinking in this regard?

Shapiro: “Amenable” is the right word. They’re probably not worth the effort to get a constitutional amendment, which I’m convinced would be required despite clever academic theories to the contrary. If the most common proposal, 18-year terms with a vacancy every two years, had been around the last few decades, the court’s makeup would hardly be different; there would now be three Bush II appointees, four Obama appointees, and two Trump appointees – in other words, still five Republican-appointed justices to four Democratic-appointed ones.

In the last 50 years, there have been 30 years of Republican presidents and 20 years of Democratic ones; if anything, liberal voices have been overrepresented. But even if term limits wouldn’t change the court’s decision-making, they might be worth trying anyway because at least there would be less randomness. As Orin Kerr put it: “If the Supreme Court is going to have an ideological direction — which, for better or worse, history suggests it will — it is better to have that direction hinge on a more democratically accountable basis than the health of one or two octogenarians.”

Question: So far as the judicial confirmation process in concerned, toward the end of your book you write: “I’ve come to the conclusion that we should get rid of hearings altogether, that they served their purpose for a century but now inflict greater cost on the Court, Senate, and the rule of law than any informational or educational benefit gained.” Do you think there is any real likelihood of this?

Shapiro: Well, there’s no law saying that the “advice and consent” process has to include hearings. The Senate didn’t even hold public hearings on Supreme Court nominations until 1916, and it wasn’t until 1938 that a nominee testified at his own hearing. But their utility has largely run its course at a time when nominees come with voluminous paper trails that are instantly accessible to all.

Maybe there would still be a need for closed sessions to consider the FBI’s background investigation, privileged documents and other ethical concerns, but the open hearings now produce more heat than light. It’s against the interest of the party not in control of the White House to dispense with the hearings — how else can their senators extract their pound of flesh? — but perhaps this is something that both parties can eventually agree on.