Empirical SCOTUS: The singular relationship between the D.C. Circuit and the Supreme Court

on Oct 3, 2019 at 10:44 am

With the Supreme Court term about to begin, many eyes will be on a small handful of cases involving certain salient issues. In this respect this term has a lot to offer. The court will review the federal government’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals policy. It will look at the constitutionality of health care mandates from the Affordable Care Act. It will even examine a New York law dealing with transporting a licensed firearm under the Second Amendment. The court has granted a total of 51 cases to review in the upcoming 2019 term. Of these cases only one, Opati v. Sudan, came from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, the court of appeals in which more Supreme Court justices got their start than any other. (Trump v. NAACP was also heard in federal court in Washington, but by the district court rather than the court of appeals.) This circuit has been acknowledged as special and unique (this article is behind a paywall) by none other than Chief Justice John Roberts. But what makes the D.C. Circuit unique, who are its judges, and what is their relationship to the Supreme Court? These questions and others will be analyzed below looking at data (partially derived from the Supreme Court Database) from cases decided between the 1986 Supreme Court term, in which Justice William Rehnquist was elevated to chief justice, and the 2018 term.

The Cases

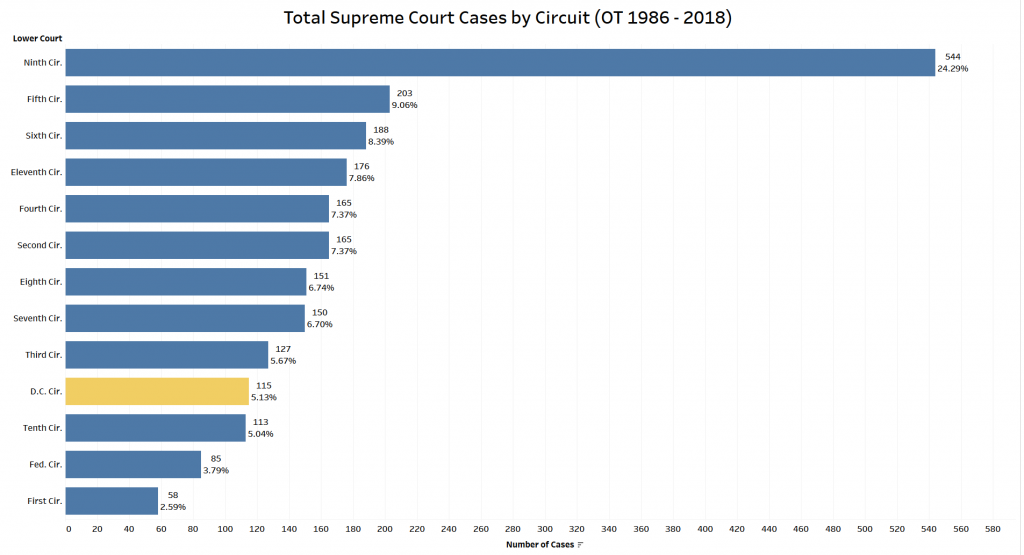

The D.C. Circuit isn’t the largest federal circuit by a long shot. According to the statistics from the Office of the U.S. Courts, the D.C. Circuit actually heard the fewest cases of any of the federal courts of appeals this past year (Statistics for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit are listed separately from those of the other circuits.). It also had the fewest cases per judge of any circuit, with each judge averaging 44 written decisions, compared to 232 written decisions per judge for judges on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit. The Supreme Court nonetheless granted more cert petitions in cases from the D.C. Circuit since 1986 than from three of the other circuits.

The Supreme Court heard nearly twice as many cases from the D.C. Circuit than from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 1st Circuit during this period, but only about a fifth as many cases as it heard from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit (As a point of reference, the 9th Circuit decided nearly 10 times as many cases as the D.C. Circuit this past year.).

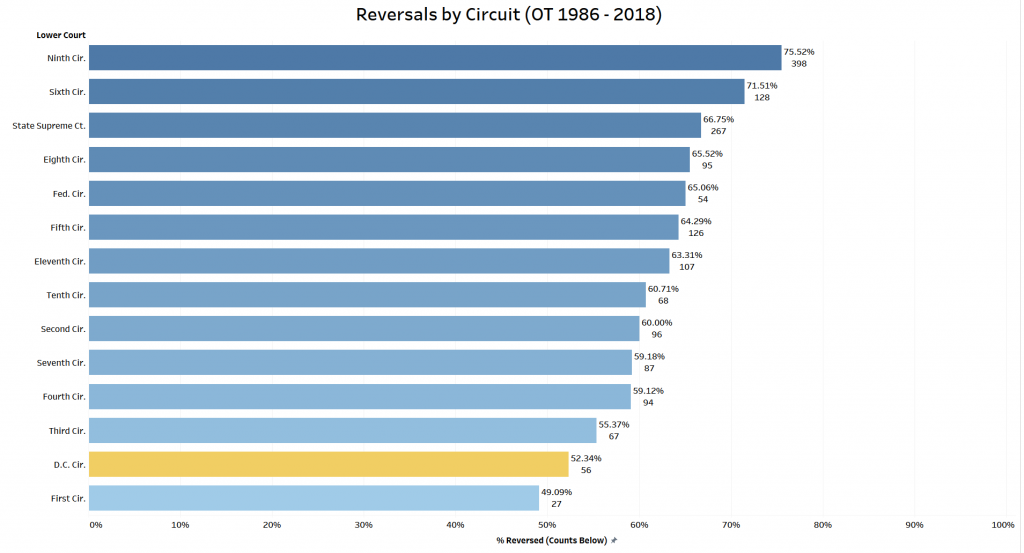

One unique area for the D.C. Circuit is Supreme Court reversals. D.C. Circuit decisions have been reversed the second-least frequently of decisions from any circuit over this period.

At 52 percent, the D.C. Circuit was reversed less frequently than all other circuits except the 1st Circuit, which was reversed 49 percent of the time. The Supreme Court reversed 64.4 percent of its total granted decisions for this period, which is 12 percent higher than for the D.C. Circuit. Five circuits averaged higher reversal rates for this period than this average, with the 9th Circuit’s 75.5 percent running the highest.

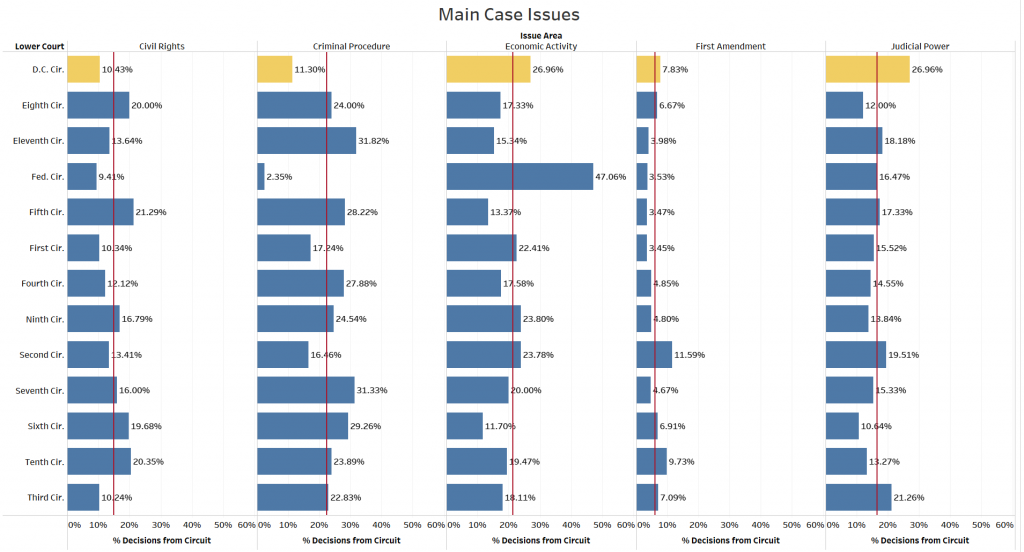

The D.C. Circuit hears a unique set of cases that make their way to the Supreme Court. According to the Supreme Court Database’s coding for issue area, cases from the D.C. Circuit that eventually make their way to the Supreme Court are much more frequent in certain common areas.

The percentages show the rate of cases within each circuit and the red lines mark the average frequency of each case area across circuits. The D.C. Circuit had well below the average rate of civil-rights and criminal-procedure cases for this period compared with rates from other circuits. It had just about the average frequency of First Amendment cases. The D.C. Circuit had a higher frequency of judicial-power cases, however, with cases in this area comprising 5 percent more of its Supreme Court caseload than those from any of the other circuits.

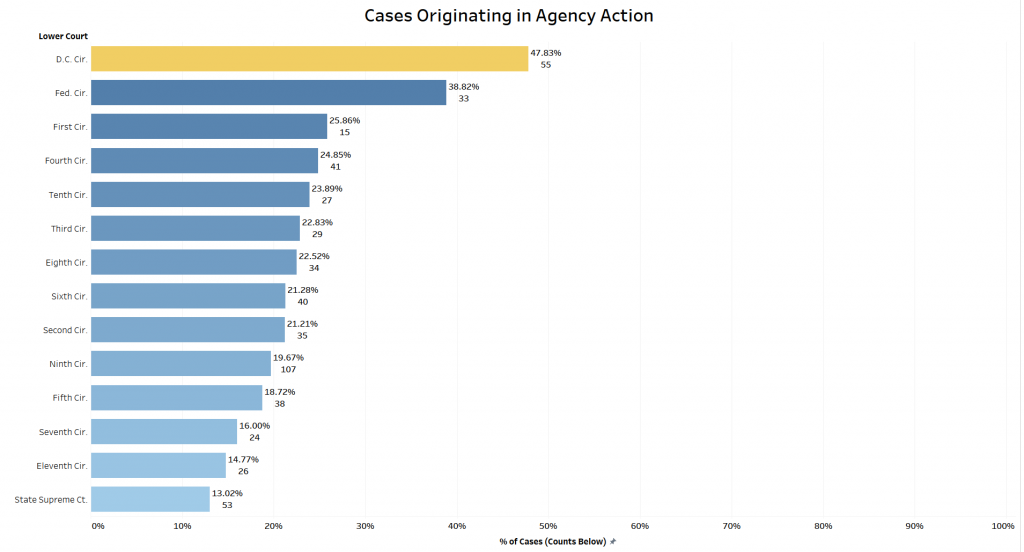

One major distinction between the D.C. Circuit and other courts of appeals is the frequency with which it hears cases originating from actions of federal agencies. As the federal appeals court based in Washington, the D.C. Circuit hears the bulk of such cases. The D.C. Circuit’s experience with such cases is apparent when comparing Supreme Court cases that originated in agency actions by circuit. The figure below shows the fraction of these cases per circuit since 1986.

Aside from the 9th Circuit, the D.C. Circuit ruled on more cases starting with agency actions than any other federal court of appeals, and at 48 percent, cases from the D.C. Circuit comprise almost 10 percent more of the Supreme Court’s administrative-law docket than cases from any other circuit (and over 25 percent more than cases from the 9th Circuit).

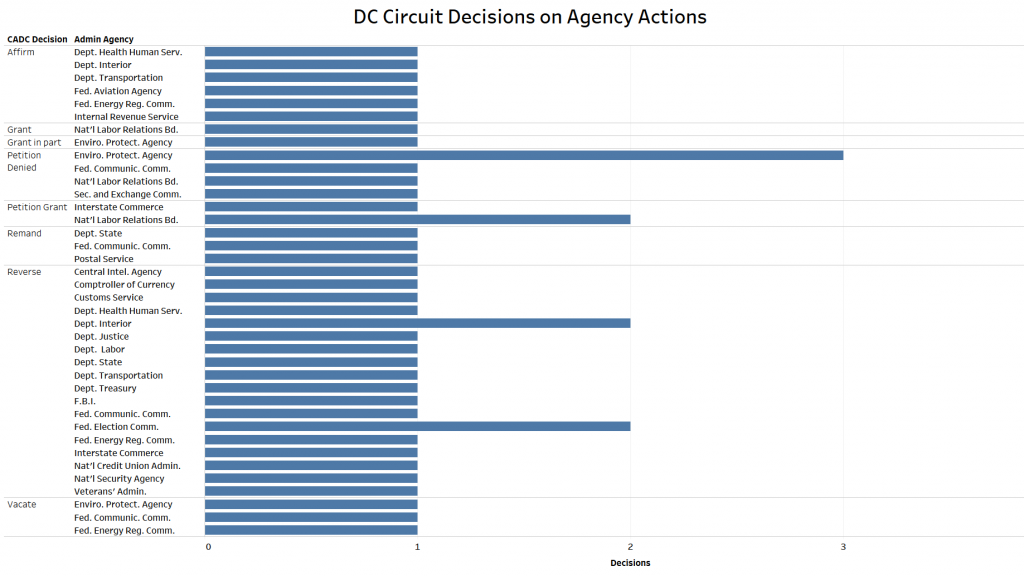

In contrast to the Supreme Court’s relatively low reversal rate of decisions from the D.C. Circuit, the D.C. Circuit reverses a relatively high number of agency decisions. The D.C. Circuit’s decisions from agency actions that later led to Supreme Court cases are displayed below.

Of the cases the Supreme Court heard during this period, only six were appeals from rulings in which the D.C. Circuit affirmed an agency’s decision. Within this set of cases, the D.C. Circuit overturned 20 agency decisions and vacated three more. Although more EPA decisions led to this set of cases than decisions from other agencies, these cases came from actions by a diverse set of agencies.

The Judges

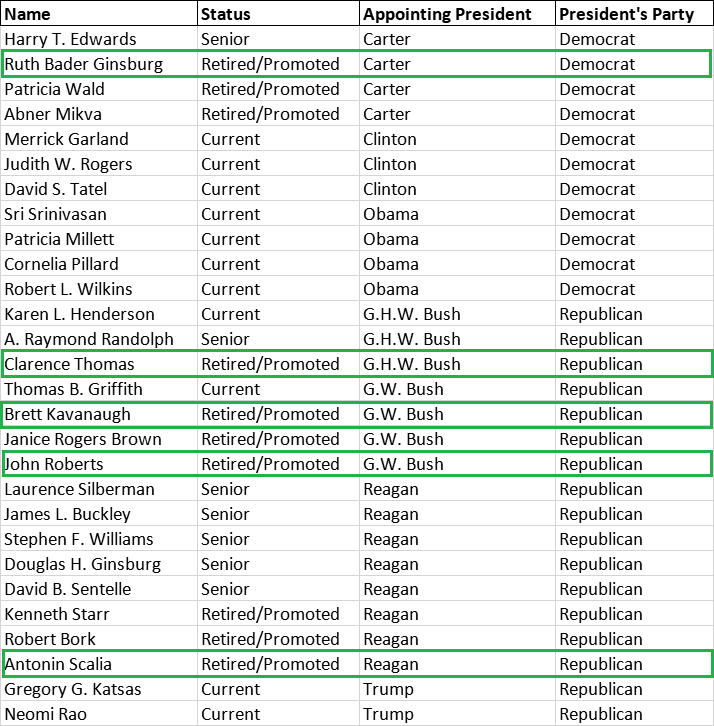

More current and recent Supreme Court justices previously served on the D.C. Circuit than on any other court. Four of the nine current justices on the Supreme Court were previously D.C. Circuit judges. The following table shows the judges who sat on the D.C. Circuit during any year from 1986 until today whose decisions led to Supreme Court cases,who currently sit on the D.C. Circuit, or who currently sit on the Supreme Court and were elevated from the D.C. Circuit, along with their current status and their appointing president. Current and past Supreme Court justices are enclosed in green.

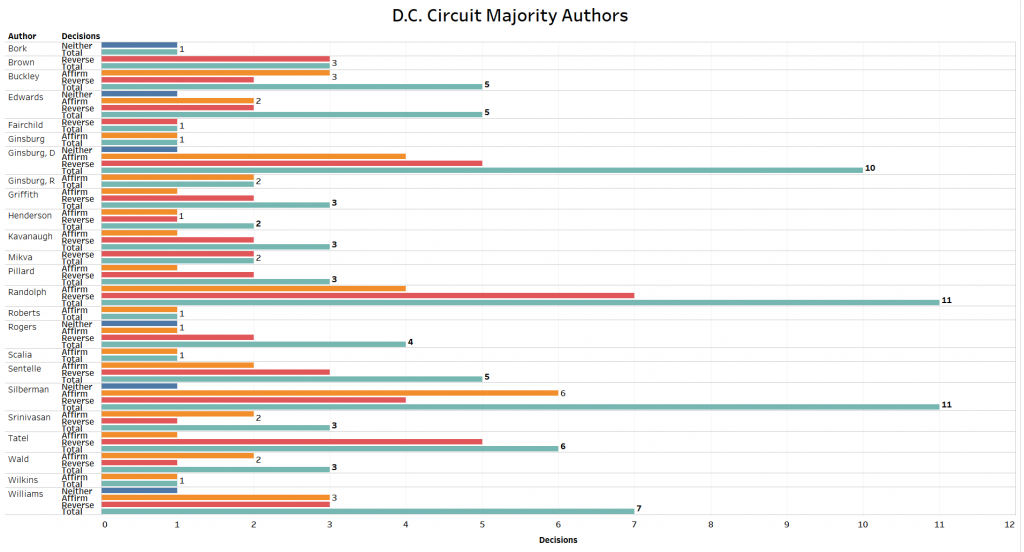

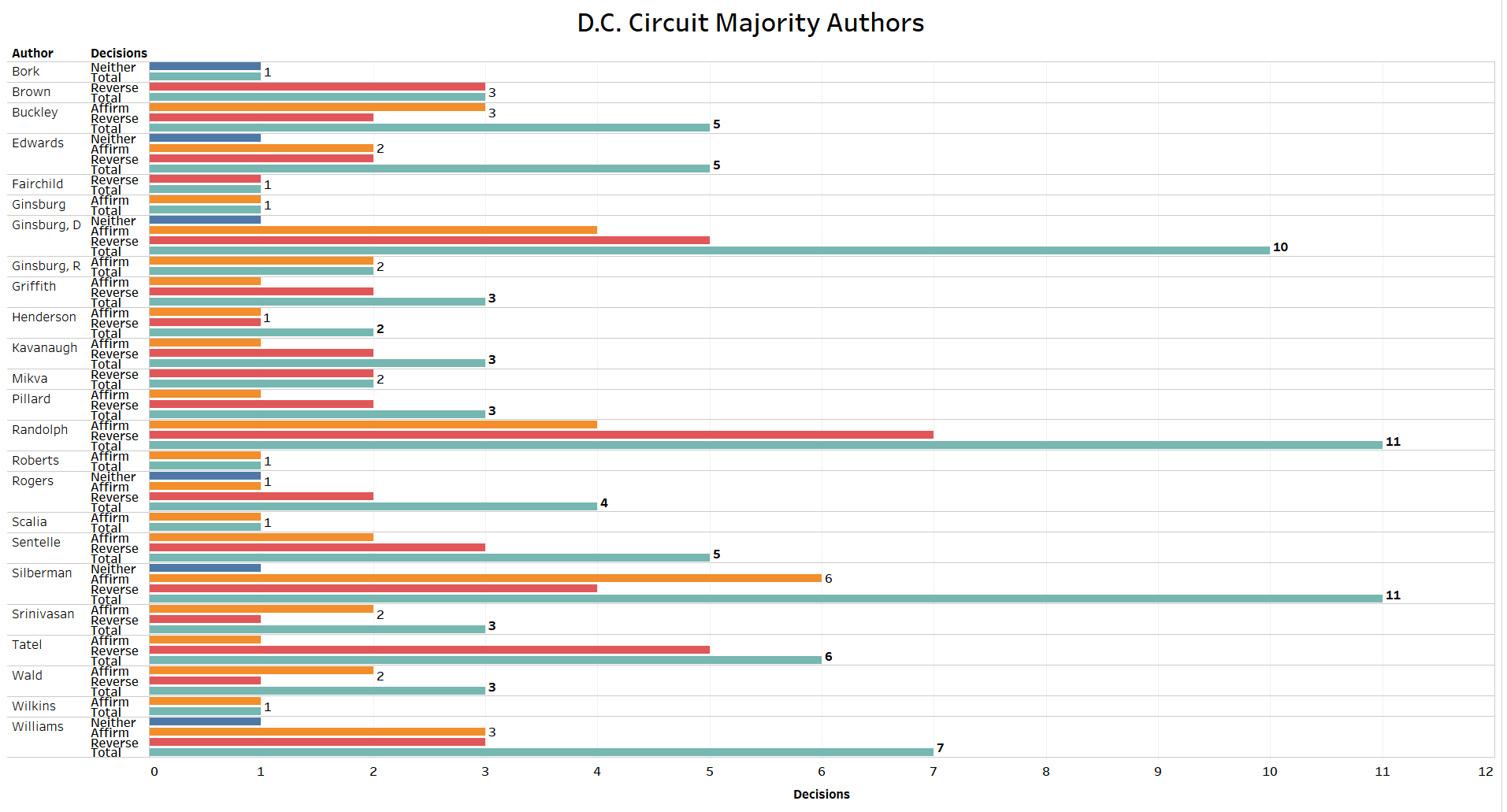

When we look at D.C. Circuit judges whose majority opinions were later reviewed by the Supreme Court, Judges Laurence Silberman and A. Raymond Randolph are tied with the most, at 11 apiece.

Outcomes coded as “neither” were judgments affirming and reversing in part or other decision types that did not clearly identify an outcome favoring one side. Randolph was also the judge reversed most often by the Supreme Court, with seven of his decisions leading to reversals. Silberman had the most affirmed opinions with six. Looking at the current Supreme Court justices, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg had both of her D.C. Circuit decisions leading to Supreme Court cases affirmed, Justice Brett Kavanaugh had two of his decisions reversed and one affirmed, and Roberts had his only decision leading to a Supreme Court case affirmed.

Not only are majority opinions telling when looking at lower court judges’ relationships to the Supreme Court, but so are dissents. Dissents in cases that are later taken up by the Supreme Court may indicate that justices took heed of the dissenters’ positions at the cert stage. The next figure shows the number of dissents from D.C. Circuit judges in cases that the Supreme Court later decided.

Judges David Sentelle and Patricia Wald lead this group, with seven dissents each in cases that the Supreme Court later adjudicated. Of current Supreme Court justices, Kavanaugh had the most dissents on the D.C. Circuit in cases later heard by the Supreme Court, with three.

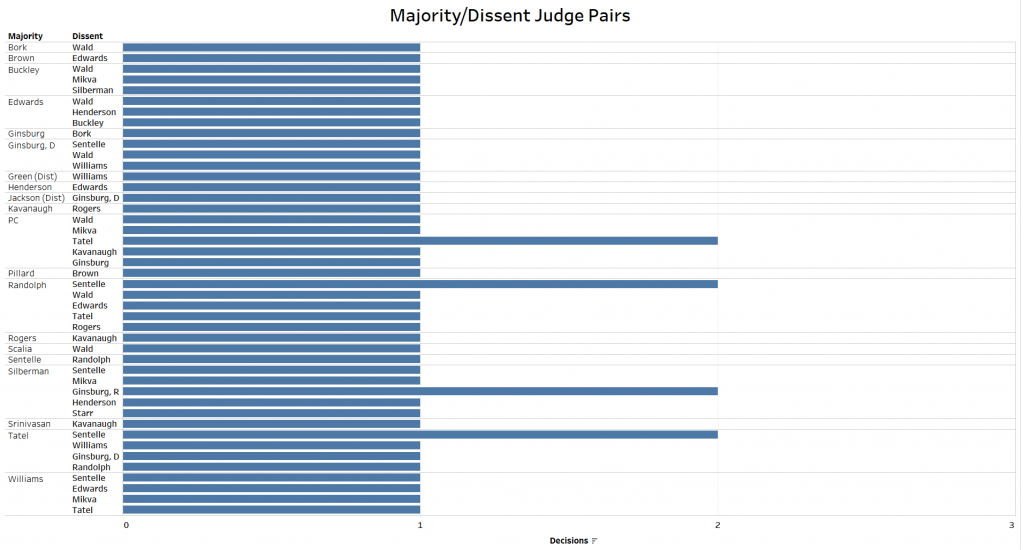

Another way to break down these relationships is by majority/dissent judge-pairs in cases the Supreme Court later heard. Of the judge-pairs, only three had more than one case that the Supreme Court later decided. “PC” cases are per curiam decisions in which no D.C. Circuit judge was listed as a majority author.

These three pairs of judges are Randolph as majority author with Sentelle in dissent, Silberman as majority author with Ruth Bader Ginsburg in dissent, and Sentelle as majority author with David Tatel in dissent. Of these three pairs, only one, Randolph and Sentelle, consisted of judges appointed by presidents of the same party (Republican).

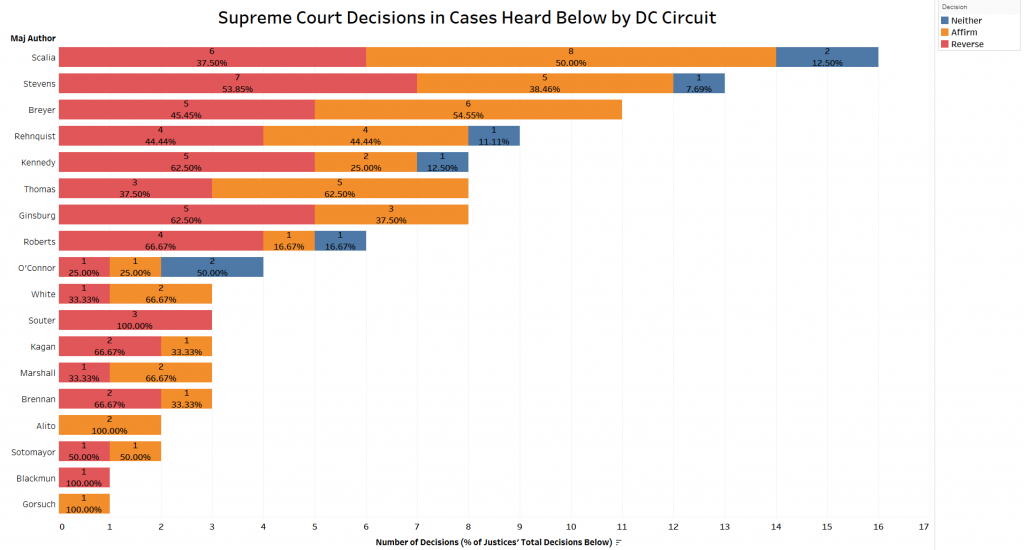

Supreme Court justices are the ultimate arbiters in this set of cases. The last figure shows how often specific justices wrote majority opinions in this set of cases and how they ruled on the D.C. Circuit’s decisions.

Justice Antonin Scalia wrote majority decisions in more of these cases than any other Supreme Court justice, with 16. He affirmed 50 percent of them and only reversed 37.5 percent. Of the justices who wrote majority opinions in at least eight cases coming from the D.C. Circuit, only Stephen Breyer and Clarence Thomas had higher affirmance rates than Scalia. Judges with high reversal rates of D.C. Circuit decisions and more than three total decisions in this set include Ginsburg at 62.5 percent and Roberts at 66.67 percent.

The D.C. Circuit hears many cases garnering a great deal of attention. Between these attention-grabbing cases and other cases that involve issues recurring in the Supreme Court, the D.C. Circuit should remain a breeding ground for Supreme Court justices for the foreseeable future.

This post was originally published on Empirical SCOTUS.