Forthcoming paper on influence of law clerks recalls Rehnquist article from 1957

on Nov 2, 2018 at 10:40 am

The specter of the law clerk as a legal Rasputin, exerting an important influence on the cases actually decided by the Court, may be discarded at once. … It is unreasonable to suppose that a lawyer in middle age or older, of sufficient eminence in some walk of life to be appointed as one of nine judges of the world’s most powerful court, would consciously abandon his own views as to what is right and what is wrong in the law because a stripling clerk just graduated from law school tells him to.

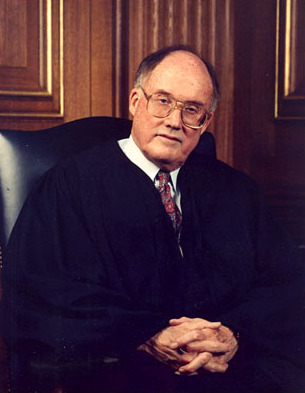

William Rehnquist – writing in a 1957 issue of U.S. News & World Report, four years after clerking for Justice Robert Jackson and 14 years before becoming a justice himself – called this the “common-sense view of the relationship between Justice and clerk” and noted the “complete absence of any known evidence of such influence.”

A paper recently accepted for publication in the Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization – “Legal Rasputins? Law Clerk Influence on Voting at the U.S. Supreme Court,” which takes Rehnquist’s quote as an epigraph – claims to offer the evidence that Rehnquist found lacking. (The paper looks at cases decided between 1960 and 2009, a period after Rehnquist’s clerkship from February 1952 to June 1953.)

Authors Adam Bonica, Adam Chilton, Jacob Goldin, Kyle Rozema and Maya Sen “find that clerks exert a modest but statistically significant effect on how justices vote”: “To interpret the magnitude of this effect, our estimate suggests that, on average, a justice would cast approximately 4% more conservative votes in a term when employing his or her most conservative clerks, as compared to a term in which the justice employs his or her most liberal clerks.”

A four percent swing might not seem like much, but it could amount to three or four votes in an 80-case term; “that’s not an insignificant effect in terms of the sheer magnitude of the findings,” Sen observes. Although recent terms have actually had fewer than 80 cases, many terms in the studied time period had more.

The authors suggest that “[t]here are at least two pathways for how such influence could occur: delegation and persuasion,” which need not be mutually exclusive. Because the authors find “substantially larger effects in cases that are higher profile (17%), cases that are legally significant (22%), and cases in which the justices are more evenly divided (12%),” as opposed to lower-profile cases that a justice might be more likely to delegate to a clerk, the authors conclude that clerks primarily influence a justice’s voting through persuasion. Sen suggests that in major cases law clerks might be more interested in speaking up and expressing personal opinions.

The authors note that anecdotally, “[i]nterviews with former clerks certainly suggest that clerks exert a significant degree of influence over their justices in specific cases,” but caution that “this view may be colored by clerks’ exaggerated sense of their own importance in the process or may represent aberrations from the norm.” At least one former clerk – Professor Daniel Epps of Washington University Law, who clerked for Justice Anthony Kennedy from 2009-2010 – nevertheless considers the study’s finding “a bit surprising.” Epps shares Sen’s “intuition that the big cases are ones in which there are more discussions among the justice and the clerks—and thus more possibility for persuasion.” But he also senses that “those are the cases where the justices have the strongest intuitions already, and thus might be least susceptible to persuasion.”

As with any empirical study, this one relies on contestable factors. For example, the authors measure clerk ideology based on political donations. As another political scientist who studies the court, Adam Feldman of Empirical SCOTUS, observes, the hypothesis that donations are an accurate proxy for ideology “seems sensible,” but other intervening factors may influence choices about where to direct contributions.

Another methodological hurdle is causal: Do clerks influence justices or do justices simply hire like-minded clerks? Sen calls this the “birds of a feather flock together” problem. For this reason, it’s analytically helpful that justices typically hire clerks one or two terms in advance. If more conservative clerks were hired by a justice during the same term as their clerkships, a more conservative voting pattern by that justice that year might simply reflect the conservative inclinations of the justice – who decided both who to hire and how to vote – at that time. But because clerks are hired well before their clerkship terms, and assuming (among other things) that justices do not hire with foresight about future changes in their own voting patterns, Sen explains, the authors “can compare justices’ changes in voting from year to year and be reasonably assured that … we are capturing the effect of those clerks in a particular term.”

Returning to Rehnquist

This is not the first academic study to consider the potential influence of law clerks. For example, in a 2011 article in the Cornell Law Review, “Judicial Ghostwriting: Authorship on the Supreme Court,” Jeffrey Rosenthal and Albert Yoon conduct a text analysis of the justices’ opinions and find that variability in their writing styles offers “strong evidence that Justices are increasingly relying on their clerks when writing opinions.”

In his article, Rehnquist acknowledged that “[o]n a couple of occasions each term,” Jackson asked clerks to draft opinions for him, “along lines which he suggested.” Indeed, Rehnquist insisted that the “result reached in these opinions was no less the product of Justice Jackson than those he drafted himself; in literary style, these opinions generally suffered by comparison with those which he had drafted.”

Concurring in Brown v. Allen, a case decided during Rehnquist’s clerkship, Jackson wrote one of his most famous literary lines: “We are not final because we are infallible, but we are infallible only because we are final.” Even as the recent study suggests that “we” in some cases may include influence from clerks, Brown does not appear to be one of those cases, at least for Rehnquist and Jackson. Rehnquist wrote a memo arguing that federal courts should grant habeas petitions involving issues considered by state courts only if the defendant had been denied the right to counsel. That recommendation did not have much “impact” on Jackson, as David Garrow wrote in a 1996 profile of Rehnquist for The New York Times, and the case has become “justly famous among criminal law practitioners as the modern fount of an expansive approach to Federal courts’ habeas jurisdiction.”

Another case in which Rehnquist seems to have been unsuccessful in swaying Jackson’s vote is none other than Brown v. Board of Education. Rehnquist wrote Jackson a memo arguing in favor of the precedent underpinning segregation, the “separate but equal” doctrine established in Plessy v. Ferguson. Jackson, instead, joined a unanimous court in overturning Plessy. Rehnquist’s memo proved controversial during his 1971 nomination to the court and 1986 elevation to chief justice. In both instances, Rehnquist claimed that the memo articulated Jackson’s views, not his.

Both of these decisions may have been part of Rehnquist’s reasons for publishing his 1957 article. As he wrote, “I commit my limited knowledge of the nonconfidential aspects of the system to public print because recent controversy about the Court’s decisions may make it of general interest.”

In that article, Rehnquist did acknowledge that law clerks, himself included, possibly affected the Supreme Court’s “certiorari work” – the process of deciding which of the many requests for review to grant each term — through “unconscious slanting of material”: “I must admit that I was not guiltless on this score.” (Clerk influence on the certiorari docket was outside the scope of the recent study.)

And along with admitting his own guilt, the conservative Rehnquist faulted his generally more liberal peers:

From my observations of two sets of Court clerks during the 1951 and 1952 terms, the political and legal prejudices of the clerks were by no means representative of the country as a whole nor of the Court which they served. … And where such bias did have any effect, because of the political outlook of the group of clerks that I knew, its direction would be to the political “left.”

Rehnquist explained that those “political and legal prejudices of the clerks” included “extreme solicitude for the claims of Communists and other criminal defendants, expansion of federal power at the expense of State power, and great sympathy toward any government regulation of business—in short, the political philosophy now espoused by the Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren.”

Rehnquist’s concern about undue clerk influence does not seem to have abated in the course of his career. “Decades after his U.S. News essay, Chief Justice Rehnquist continued to fear the influence of clerks,” as Adam Liptak wrote for The New York Times in 2008. Liptak pointed to a 1996 memo Rehnquist wrote to his fellow justices in which he expressed concern about a certain practice within the cert pool, a labor-saving device in which a petition is first reviewed by one law clerk for all the participating justices.

Even as clerks are increasingly in the news – from the Heritage Foundation’s now-cancelled “Federal Clerkship Training Academy” to Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s first-ever all-female team of Supreme Court clerks – the role of clerks remains a “perennial topic of interest about which little is known,” as Bonica, Chilton, Goldin, Rozema and Sen write in their introduction. Articles like theirs and Rehnquist’s help to shed more light on this underappreciated aspect of the American judiciary.