Empirical SCOTUS: Indirectly inferring Kavanaugh’s position in abortion cases

on Jul 26, 2018 at 11:58 am

Many people seems to be wondering how Judge Brett Kavanaugh will vote in abortion cases if confirmed to the Supreme Court, and more specifically if he will vote to overturn Roe v. Wade. Kavanaugh has only written a decision in one case regarding abortion — Garza v. Hargan. In that case, he did not stake out a position on the constitutionality of abortion, as his dissent pertained to whether the government’s involvement would lead to an undue burden on obtaining an abortion. He also did not join Judge Karen Henderson’s opinion, which much more directly critiqued the constitutionality of the detained minor’s receiving an abortion.

Aside from this, the closest we get to Kavanaugh’s position on abortion is a 2017 speech he gave to the American Enterprise Institute in which he discussed Rehnquist’s dissenting opinion in Roe. Although he did not directly articulate his position on abortion, his logic could be construed as positioning him as anti-abortion. The relevant paragraph from the speech reads:

In this context, it’s fair to say that Justice Rehnquist was not successful in convincing a majority of the justices in the context of abortion either on Roe itself or in the later cases such as Casey, in the latter case perhaps because of stare decisis. But he was successful in stemming the general tide of free willing judicial creation of unenumerated rights that were not rooted in the nation’s history and tradition. The Glucksberg case stands to this day as an important precedent, limiting the Court’s role in the realm of social policy and helping to ensure that the Court operates more as a court of law and less as an institution of social policy.

This support of Washington v. Glucksberg, and specifically of its significance as a case that does not give significant credence to unenumerated rights, does not easily accord with a pro-abortion-rights stance. Nonetheless, Kavanaugh did not speak directly to abortion, instead offering a hierarchy of different types of rights and a general reflection that unenumerated rights like a right to privacy should not hold as significant a position in constitutional adjudication as rights that are clearly spelled out in the Constitution.

On balance and with little information pointing in either direction, one would not be wrong to say that based on this evidence, Kavanaugh is more likely than not in the anti-abortion camp. This, however, may not be the only way to gauge Kavanaugh’s position on this issue.

A very interesting 2008 article in the American Economic Review by Ebonya Washington, brought to my attention by @NYCNavid, examines the tendency for congressmen and women to vote more liberally on reproductive-rights issues based on the proportion of daughters they have. In the words of the study’s author, the study “find[s] that conditional on number of children, parenting an additional female child increases a representative’s propensity to vote liberally on women’s issues, particularly reproductive rights.”

The cases

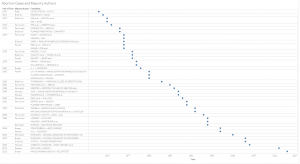

This hypothesis is easily testable at the Supreme Court level because all of the relevant data are available, mainly from the United States Supreme Court Database. A breakdown of the cases coded as focusing on abortion and the majority-opinion authors looks as follows:

Since before Roe, the Supreme Court has had a regular slate of abortion cases across the years, although they have recently become sparser. This is likely a result of the court’s decreased willingness to hear the cases, not a lack of petitions to the court.

To get a more precise sense of voting coalitions in these cases, the next figure shows the number of times justices voted in the majority versus in dissent in this set of cases.

Across the decades, the more liberal justices have been in dissent more often than their conservative counterparts. Justices Harry Blackmun, John Paul Stevens, Thurgood Marshall and William Brennan lead in dissenting vote count, while Rehnquist voted in the majority in the most of these cases. This analysis becomes a bit more nuanced when we look at the types of opinions these justices authored.

In a manner related to the previous figure, Rehnquist wrote the most majority opinions, followed by Blackmun. Blackmun also wrote the most dissents. Stevens, who dissented the second most frequently, also had the most special concurrences, indicating that even when he sided with the majority he often did so based on different reasoning.

Other factors

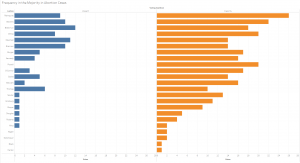

Clearly the conservative and liberal justices have taken opposing sides in the abortion cases. More than a quarter of these decisions came down to a one-vote difference between the majority and dissent. We can see this difference graphically when we look at the justices’ votes coded as liberal or conservative in these cases in the Supreme Court Database.

At the top, Rehnquist and Justice Byron White clearly tended to vote on the conservative side in these cases, while Stevens, Blackmun, Marshall and Brennan were likely to vote in the liberal direction. Justices Anthony Kennedy and Sandra Day O’Connor, both seen as swing justices, also both voted predominantly with the conservatives, although to a lesser degree than some of their more conservative counterparts.

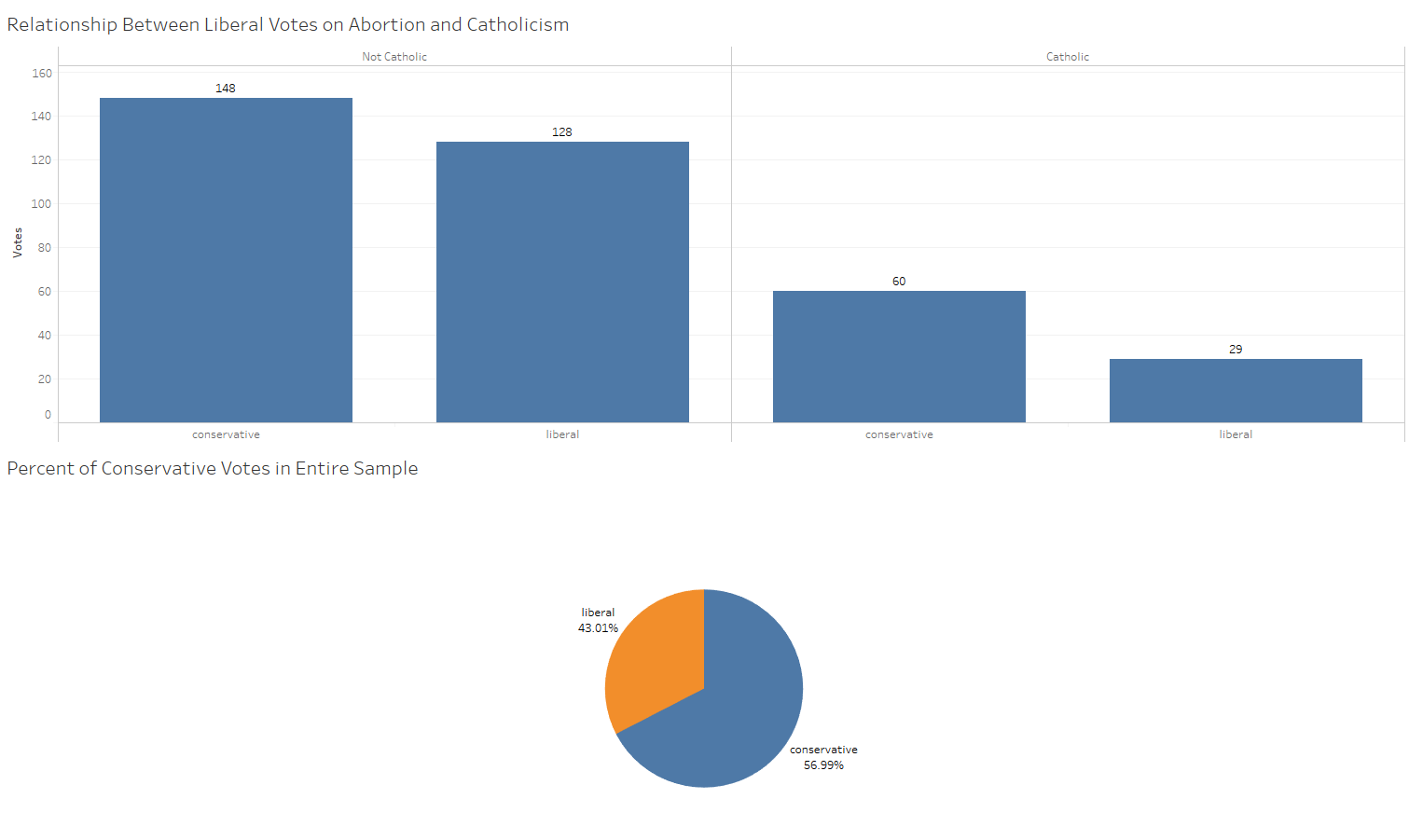

Another possibility is that the justices’ religious beliefs play a role in determining their decisions in abortion cases, as Catholicism in particular opposes most forms of abortion. Although justices have clearly indicated in their confirmation hearings that their religion did not and would not affect their decision-making, this might still be a subconscious influence even if not an overt motivator. Catholic judges in the preceding figures include: Kennedy, Justice Antonin Scalia, Brennan, Justice Clarence Thomas, Chief Justice John Roberts, Justice Samuel Alito and Justice Sonia Sotomayor. Kavanaugh is also Catholic.

Most of the Catholic justices (aside from Sotomayor and Brennan) are conservative, which makes the effects of the two factors difficult to disentangle. Comparing Catholic justices’ votes to those of non-Catholics, we see the interplay between religion and ideological perspective. The top graphs below show the ideological direction of votes from Catholic and non-Catholic justices. The pie chart below looks at the overall fraction of liberal and conservative votes across all justices in these cases.

There are several important pieces of information here. The justices as a whole were more likely to vote conservatively in these cases than liberally. This was true for Catholic and non-Catholic justices. Catholic justices who were and are more frequently conservative in their own preferences tilted more toward conservative votes in abortion cases than the liberals. The 53 percent conservative vote from non-Catholic justices is, however, much closer to the near-57 percent for all justices than is the 67 percent conservative vote for the Catholic justices.

Relationship to daughters

The study of congressmembers’ positions on abortion looked at the proportion of daughters as the main factor related to more liberal views on abortion. This post also looks at the justices’ absolute count of daughters as plausibly related to more liberal views on abortion. First a look at the breakdown of the justices’ children by gender.

All but six of the justices listed above have at least one daughter. Six had multiple daughters, and Scalia had the most with four. Fifteen of the justices had at least one son and one daughter.

This fraction of daughters was then calculated for these 15 justices. Next, I generated two regression equations looking at the relationship between counts of daughters or proportion of daughters and liberal votes in abortion cases while controlling for the justices’ ideologies, whether the justices were Catholic, whether the case was decided by one vote or not, whether a given justice was a woman, and whether they voted for the petitioner or not (a common control variable in such studies because the justices tend to vote for the petitioning party well over 60 percent of the time). [Note: One need not be able to interpret regression results to understand the gist of the results.]

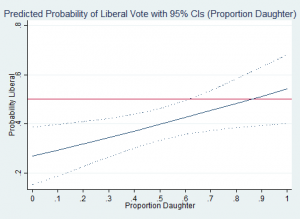

The results of these equations allowed for the generation of graphs that look at the probabilities that the justices would vote liberally in abortion cases based on their number of daughters as well as on their proportion of daughters. First, a graph based on the number of daughters ranging from zero to five. The reference line marks 50 percent likelihood of a liberal vote and the outside lines mark 95 percent confidence intervals.

The line here is upward-sloped, indicating that having more daughters is related to more liberal votes on abortion. As the pie graph above shows, the justices voted conservatively on balance more frequently than liberally. As the number of daughters increases to four and five, however, the justices became more likely to vote liberally in such cases. Kavanaugh, with two daughters, falls below the 50 percent probability marker in this graph, although only slightly.

A similar result is shown for proportion of daughters.

As the justices move from zero to 100 percent daughters in proportion to sons, they become increasingly likely to vote liberally in these cases. Although the probability moves in the upward (more liberal) direction, even justices with only daughters are just slightly more likely than not to vote liberally in abortion cases. This result is intriguing because it highlights the justices’ conservative baseline in these cases. Because Kavanaugh has only two daughters, his predicted probability of voting liberally in abortion cases based on this graph is over 50 percent.

For those interested in more on the regressions, robust standard errors were used in both equations and both Daughters variables were significant at p-levels less than .05.

Concluding thoughts

The results above are obviously not deterministic. They show a correlation between numbers of daughters or proportion of daughters and the likelihood that a justice votes liberally in abortion cases. Other factors, especially a justice’s ideological predisposition, also play roles in this calculus.

On the other hand, these results show that even after controlling for several possibly consequential factors in the justices’ decision making, the number of or proportion of daughters relates to the justices’ decisions in these cases. Because Kavanaugh has two daughters and no sons, we might infer a greater likelihood that he would vote liberally in these cases than other justices with fewer daughters or lower proportions of daughters.

This does not mean Kavanaugh will not vote to overrule Roe. It also doesn’t mean he will vote to overturn it if given the chance. It does suggest a somewhat blunting effect of daughters and that this might play a role in Kavanaugh’s decisions in the reproductive-rights area.

This is also a first cut at examining this relationship. A more thorough study might look beyond the small sample size of the Supreme Court to gain more statistical leverage out of a larger sample. The downside to such a study, though, at least in relation to the topic of this post, is that it would be divorced from the Supreme Court, which is a unique institution in our federal system and is at the center of the question at hand.

Even though this post does not provide a conclusive answer for how Kavanaugh will vote in these cases, it should at very least provide some additional food for thought on factors that might influence Kavanaugh and the other justices when making decisions in this area.

This post was originally published at Empirical SCOTUS.