Empirical SCOTUS: A seismic shift?

on Jun 7, 2018 at 3:36 pm

It seems out of a script by the writers of the film “Groundhog Day.” At the end of the term each year, court-watchers await the impending retirement of a justice. Stories break in the months before June trying to sort through the imperfect information concerning such retirement plans. In recent years, speculation of an impending retirement has surrounded several justices, including Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Clarence Thomas and, most notably, Anthony Kennedy. With rumors swirling around the possibility of Kennedy retiring at the end of the term, this post examined the likelihood of such a move. Pieces like these raise the specter of a retirement, but generally do not examine the potential implications of such a decision. This present post uses data through the 2016 term to look at the justices’ voting pairs and how they might shift if Kennedy does retire at the end of the term. (Justice Neil Gorsuch is removed from the analyses due to too few observations.)

The setting

The battle lines have been drawn. At least Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, Republican of Kentucky, would like to think they have. With the failed nomination of Chief Judge Merrick Garland to the Supreme Court and Gorsuch’s subsequent nomination and confirmation, the Supreme Court’s conservative majority remained intact after the passing of Justice Antonin Scalia. This majority, however, is not always steadfast. Kennedy, whose choices affect the outcomes of more closely contested Supreme Court decisions than any of the other justices on the court (for support for this characterization see pages 27-30 of my article “Reframing the Confirmation Debate”), is hardly predictable. Sometimes on the left and other times on the right, he has written some of the most important majority opinions on the recent court.

This week, Kennedy authored the majority opinion in Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission. The majority coalition consisted of an interesting mix of justices including two of the four more liberal members of the court — Justices Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan. One reaction to the ruling is that Chief Justice John Roberts, a skilled tactician, helped form this diverse majority coalition as a compromise to an alternative of a much broader decision that would have split the justices 5-4 along ideological lines. If that theory is correct, this at least tacit agreement might foreshadow a key decision-making characteristic of the next iteration of the Roberts court.

Kennedy’s role

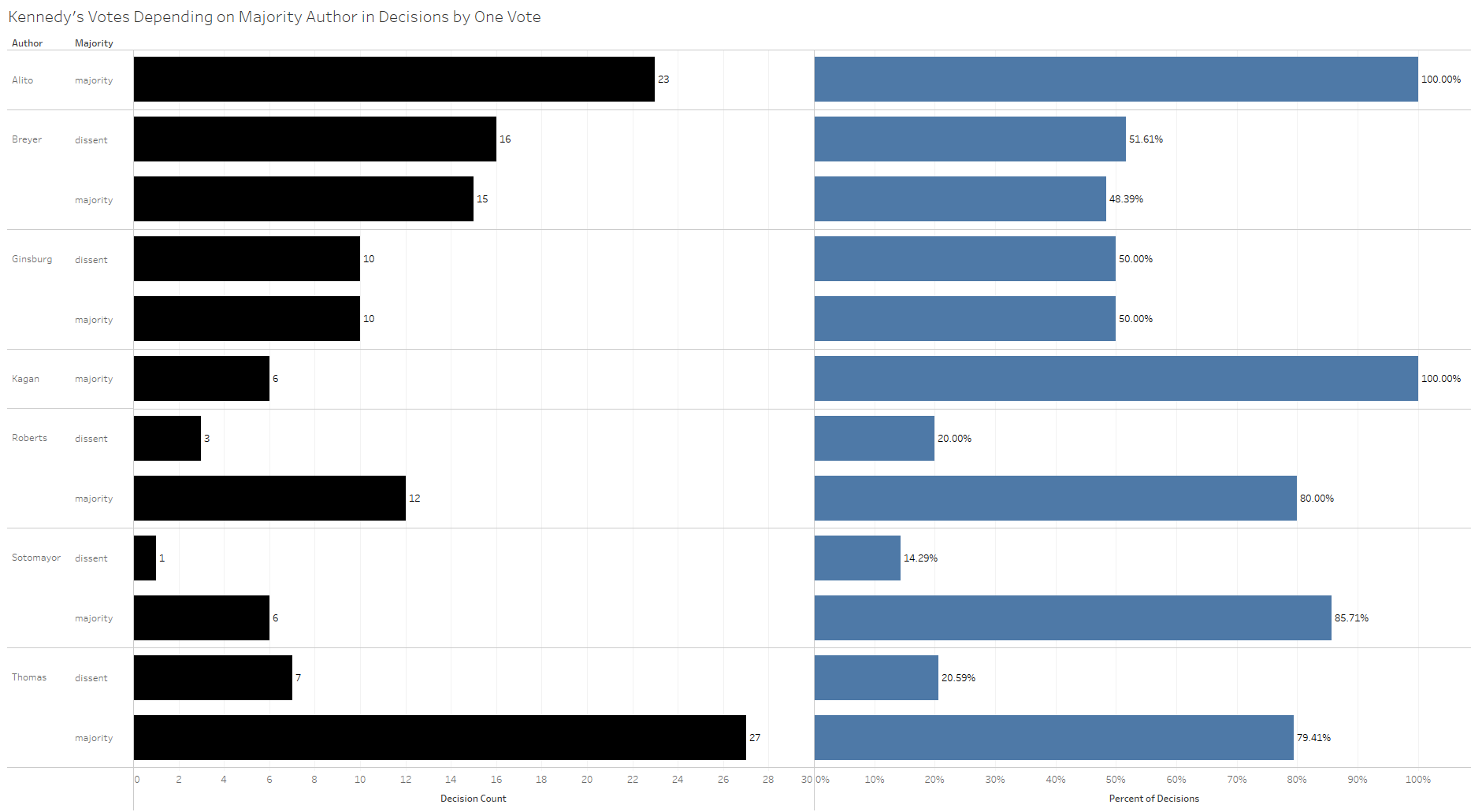

In some ways Kennedy appears to statistically side with the right over the left. Take for example cases decided by a single vote in which Kennedy did not author the majority opinion. In these cases, he has shown a greater tendency to support the conservative justices’ positions than those of the liberal justices.

While Kennedy was only in the majority when both Justice Samuel Alito and Kagan authored such decisions, he was much more likely to side with a Roberts or Thomas opinion than he was to side with a Ginsburg or Breyer opinion (Alito also wrote many more such decisions than Kagan).

The figure below shows that although Kennedy overwhelmingly sides with Kagan and Alito when they write majority opinions, he has about the same level of support for the remaining justices.

In a similar fashion, the other justices show high levels of support for Kennedy when he authors majority opinions. All of the justices’ percentages do not add up to 100 percent because of votes that are not entirely for the majority or dissent in certain cases.

While Roberts, Justice Sonia Sotomayor and Breyer show the highest level of support for Kennedy, the other justices support him around 65 percent of the time.

Both in terms of his votes and votes for his positions, Kennedy seems to straddle the ideological fence between the court’s left and right. The other justices’ allegiances are more coherent. Without Kennedy and with the addition of a new justice on the right, conservative forces would appear to have an impregnable grip on the court’s majority in ideologically laden cases. The justices would also adapt their decision-making to the court’s new composition. Their past positions and alignments give us some notion of whom they will align with if Kennedy retires at the end of the term.

Pairwise agreement

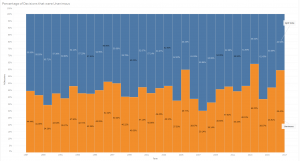

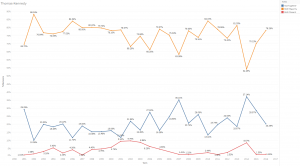

The analysis of voting pairs, 28 in all based on every combination of the eight justices after Gorsuch is removed, looks at three aspects of each voting pair — votes together in the majority, votes together in dissent, and votes not together. A baseline is helpful — the percentage of opinions each term with a unanimous vote.

The average number of unanimous decisions since Kennedy joined the court in 1987 has been around 50 percent. It was highest in 2013 at 64 percent and lowest in 2007 at 30.14 percent. There appears to be a mildly upward trajectory in recent terms, although there is also a consistent year-to-year fluctuation in the data that has increased between recent terms.

With this in mind, we begin with Roberts and Kagan and see something unique for the justices.

Roberts and Kagan are the only pair who have not dissented together in the same case. Their upward trajectory of agreement since 2013 seems to somewhat parallel the move in the justices’ unanimous voting behavior for those years, but the increase in recent years is also notable because Roberts may become the court’s new median justice (ideologically) if Kennedy retires.

Next are Roberts and Breyer.

Although they infrequently dissent together, Breyer and Roberts also have a high rate of agreement in the majority. This rate falls below that of Roberts and Kagan just a bit, although this is another pair who should maintain positions in the court’s majority for many of the court’s future decisions.

Roberts and Ginsburg are the next pair.

These two justices have dissented together in limited instances over the years. Their level of agreement, although increasing in recent years, falls below those of Roberts with either Kagan or Breyer. The increase appears rather to track the upward movement of the justices’ unanimous voting rate. We may see an increasing fragmentation of these two justices if the court’s polarization increases with the addition of a new justice.

We can see similar movement in the voting relationship of Roberts and Sotomayor.

As with Roberts and the other liberal justices, Roberts and Sotomayor show an increase in sharing the court’s majority over the past few years. Although some of the increasing consensus might have related to the court’s vacant seat for parts of the 2015 and 2016 terms, the 2017 term should provide relevant data on whether these justices stay at this level of consensus or if the level of consensus decreases again. Like the Roberts and Ginsburg pair, the Roberts and Sotomayor pair may well fall back into old patterns with the addition of another conservative justice.

The next set of justices are from the conservative end of the court. This begins with Roberts and Thomas.

Roberts and Thomas hit a rocky patch in the 2014 term but seemed to recover over the past couple of terms. When their consensus in the majority decreased in 2014, though, they agreed more frequently in dissent. If a new conservative justice were to join the court, we might see more fractures between these two justices, as Thomas will likely remain toward the court’s right edge while Roberts moves closer to the court’s middle.

The Roberts and Alito pair has been a stronger force than that of Roberts and Thomas in recent years.

Even though this pair had their lowest agreement rate in 2014 as well, they have both been in the majority an average of over 80 percent of the time since 2009. Their rate of common dissents is also more substantial than that of Roberts and Thomas.

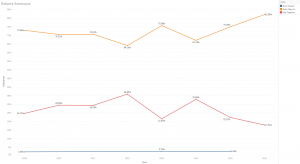

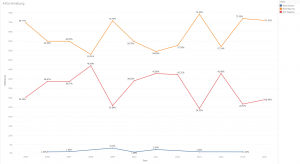

As Roberts has been a regular fixture in the court’s majority in recent terms, he has become a frequent voting partner of Kennedy’s.

Kennedy is an infrequent dissenter and so the line of common dissents is lower than those for Roberts and more conservative justices. Roberts and Kennedy are the only pair so far with a rate of 90 percent or more in the majority for a term (in 2016). This also may portend Roberts becoming a more regular member of the court’s majority if Kennedy leaves the court at the end of the term.

Moving on to other justice pairs with at least one justice from the court’s conservative wing, the next pair is Thomas and Kagan.

Thomas and Kagan had one term with over 70 percent agreement in the majority in 2013. They hardly ever dissent together and although their rate of agreement in the majority has increased since 2014, this moves alongside the increase in overall unanimity. Increasing polarization in the court will likely drive these two justices farther apart.

Thomas and Breyer typically have a lower level of agreement than Thomas and Kagan.

These two justices seesaw around a 50 percent shared frequency in the majority by term. This has increased to over 60 percent in a few terms and once dipped below 40 percent. Their shared dissents are quite irregular. This pair may push farther apart than Thomas and Kagan in future years.

Thomas and Ginsburg’s level of agreement is also somewhat inconsistent, although it tends to hover above that of Thomas and Breyer. These two also occasionally dissent together and do this a bit more often than Thomas and Breyer.

Although this pair has shown a greater likelihood of reaching consensus than the Thomas and Breyer pairing, the fluctuations in their agreement over the years shows a lack of stability that may play a greater role in diminishing their agreement if a more conservative justice takes Kennedy’s place.

The Thomas and Sotomayor pairing seems a bit more stable than that of Thomas and Ginsburg.

While the majority consensus marker for Thomas and Sotomayor was similar to that of Thomas and Ginsburg, it hit a lower point in the 2014 term. The movement between these two should be similar to that of Thomas and Ginsburg and their rate of overlapping votes may decrease in future terms.

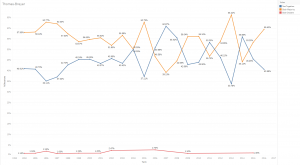

The consensus level is, not surprisingly, much higher between Thomas and other conservative justices like Alito.

Thomas and Alito tend to share the same votes in many cases both in the court’s majority and dissent. Their rate of disagreement jumps around quite a bit, going from over 22 percent to less than 6 percent in recent terms. Although we can expect them to vote together frequently in the majority and in dissent moving forward, their rate of disagreement will be telling of whether they will be a cohesive pair in future terms.

Thomas is in the majority with Kennedy at around the same rate as he is with Alito.

One marked difference between the Thomas and Alito and Thomas and Kennedy pairs is that Thomas and Kennedy share a higher rate of disagreement that has increased in recent terms. This may signal Thomas’ move farther to the right, which would likely continue to be a distinguishing characteristic of his with another conservative justice added to the court.

Although Kagan and Alito have hardly ever dissented together, their agreement rate in the court’s majority has been over 75 percent several times in recent terms.

As with Thomas and Roberts, Kagan has had an increasing rate in the majority with Alito since 2014. This pair’s highest agreement rates have been across the past two terms. While their agreement may not keep up at this rate moving forward, it may stay at a steady level and higher than those of Alito and other liberal justices on the court.

Alito and Ginsburg’s agreement rates have remained a bit below those of Alito and Kagan.

These two have a similar increase in consensus rate since 2014, although the peak of this rise was in 2015 for Alito and Ginsburg rather than in 2016 as it was for Alito and Kagan. The inability of these two justices to maintain this trend in 2016 points to the possibility that they will disagree with an increased frequency with an additional conservative justice on the court.

Alito’s agreement rates with Breyer are predominantly just a shade lower than his rates with Kagan.

Although Alito and Breyer had a dip in their rate from 2015 to 2016, this dip was less substantial than that for Alito and Ginsburg. The Alito and Breyer consensus rate also appears much more stable than that between Alito and Ginsburg. While the Alito and Breyer dissensus rate may increase again in future terms, it will probably not rise to the levels of those between Alito and Ginsburg.

While Alito’s agreement rates with the other liberal justices dipped between the 2015 and 2016 terms, this rate increased between Alito and Sotomayor over these years.

This upwards movement may signal the potential for this pair to agree more often in future terms even if Alito’s agreement rates with Breyer and Ginsburg both dip. This may be further clarified by the pair’s agreement rate for the 2017 term, now that the court is back to its nine-justice composition.

Alito’s agreement rate with Kennedy was typically above that of Kennedy and Thomas.

This agreement was fairly stable as Alito and Kennedy were both in the majority around 80 percent of the time. Alito’s disagreement rate with Kennedy reached its lowest point in 2014, the same term as Kennedy’s low point with Thomas. The somewhat higher agreement rate of Kennedy and Alito suggests that Alito is closer than Thomas to the court’s midpoint.

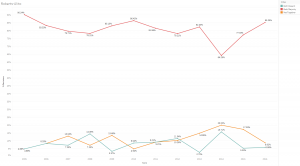

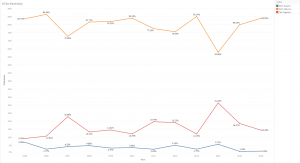

For the most part, Kennedy was in the majority more often with the liberal justices in recent terms than he was with the more conservative justices. This is especially evident in his shared frequencies in the majority with Kagan.

Kennedy and Kagan’s 93.33 percent agreement in the majority rate for 2015 is only the second 90-percent-plus agreement rate in a term that we have seen so far. Kennedy’s increased agreement rate with Kagan possibly relates both to Kennedy’s movement to the left and Kagan’s movement towards the court’s center. This also points to the possibility that Kagan will be one of the more centrist liberal justices on a court with another conservative member.

Ginsburg’s agreement rate with Kennedy tends to be lower than Kagan’s.

This rate has stayed its course with mostly upward movement since 2010, with minor dips in 2014 and 2016. This recent increase in agreement between Ginsburg and Kennedy is likely both a product of the court’s increased unanimity in recent terms and of Kennedy’s slight shift to the left.

Like that for Kennedy and Kagan, Kennedy and Breyer’s agreement rate in the majority also surpassed the 90 percent mark once in recent terms.

Breyer’s rate of agreement with Kennedy is a bit more stable than that between Kennedy and Ginsburg and tends to stay just a bit lower than that of Kennedy and Kagan. This stability shows the possibility that Breyer’s position has moderated a bit in recent terms. Similar to Kagan’s, Breyer’s agreement rate with Kennedy in 2017 will likely be indicative of Breyer’s frequency in the court’s majority in future terms.

As Sotomayor tends to fall more to the liberal end of the spectrum than either Breyer or Kagan, her levels of agreement with Kennedy are, for the most part, lower than those between Kennedy and these other justices.

Although Sotomayor and Kennedy average a similar agreement level to that of Kennedy and Ginsburg, their agreement rate appears much more stable. They have not dissented together for the past two terms though, even as their agreement levels in the majority have risen. This is likely related to Kennedy’s infrequency dissenting. The 2017 term will also give us much more insight into Sotomayor’s future movement and response to a potentially more conservative court than was provided by the past couple of terms.

Kagan and Breyer have increased in agreement in an almost consistent upward trajectory since Kagan joined the court in 2010.

Breyer and Kagan’s common dissent frequency is below those of most of the conservative justice pairs, but the level of agreement in the majority increased to over 90 percent in 2015 before dipping slightly in 2016. Although these two may become more isolated on the left side of the court with the addition of another conservative justice, they will likely be less so than Sotomayor or Ginsburg.

Kagan and Ginsburg’s level of agreement in the majority is below that of Kagan and Breyer’s in recent terms.

Kagan’s level of agreement with Ginsburg in the majority in earlier terms was occasionally above that of Kagan and Breyer, although it has moved slightly below that level over the past couple terms. While another conservative justice may push Ginsburg farther to the left than Kagan, they might also find themselves more frequently in the same coalitions in opposition to the more conservative justices.

While Kagan and Sotomayor’s level of agreement has often been similar to that of Kagan and Ginsburg, Kagan and Sotomayor’s rate of disagreement has been higher than that of Kagan and Ginsburg in recent terms.

One lingering question will be whether Kagan and Sotomayor’s disagreement level in 2015 was an aberration or whether it is part of a greater pattern of disparate views. This will very possibly be clarified by the end of the 2017 term as we should have then a better sense of whether Sotomayor and Kagan will maintain their status-quo voting relationship or if their agreement level will dip a bit in future terms.

Ginsburg’s agreement rate with Breyer has been much less stable than that of Ginsburg and Kagan.

While Breyer and Ginsburg’s level was typically lower than that of Ginsburg and Kagan in earlier terms, it has risen in recent terms. The lack of stability in this relationship, though, brings into question whether they will frequently align together in future terms. One sign that they may is through their agreement rate in dissent, which on average surpasses that of Breyer or Ginsburg with any of the other liberal justices.

Although a bit more stable than that of Breyer and Ginsburg, Breyer and Sotomayor’s level of agreement in the majority has often been below that of Breyer and Ginsburg.

Breyer and Sotomayor’s rate of shared dissents has been similar to that of Kagan and Breyer and below that of Ginsburg and Breyer. Although we will likely see Breyer and Sotomayor vote in the same direction moving forward, they may do so less frequently than do the pairs of Breyer and Kagan or Breyer and Ginsburg.

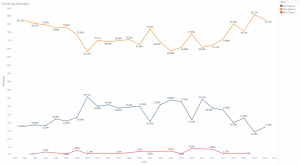

Ginsburg and Sotomayor have had a fairly high level of common dissents that has typically surpassed that of Breyer and Sotomayor.

Ginsburg and Sotomayor’s level of agreement in the majority almost parallels that of Breyer and Sotomayor at a steady rate of around 80 percent. The high level of shared dissents and shared occasions in the majority hints at the likelihood that they will share a robust voting relationship on the court moving forward.

Without complete data for the 2017 term, much of our understanding of how the justices will vote with another conservative justice on the court is incomplete. The 2015 and 2016 terms both largely lacked a ninth justice. The justices seemed to find ways to increase their consensus during this time.

With several ideologically fractured 5-4 votes so far this term, we may be observing a return to the justices’ pre-2015 patterns. Another conservative justice on the court has the potential to polarize the justices even further. With a strong coalition on the right, there will be a few justices who could move in various directions.

Moving forward, Breyer and Kagan may move from the left side of the court more toward its center, along with Roberts from the right. This will likely only be the case if they along with Roberts can help bring consensus to the rest of the justices who fall closer toward the court’s ideological poles. The votes and opinions in Masterpiece Cakeshop present an excellent example of how such a system could function. If these justices fail to raise the level of consensus on the court, then we should expect highly fractured relationships, with the four more liberal justices forming a stronger coalition on the left in opposition to the stronger conservative majority formed with a new justice whose positions will likely be to the right of Kennedy’s.

This post was originally published at Empirical SCOTUS.