Empirical SCOTUS: To extend or not to extend

on Apr 25, 2018 at 4:28 pm

Occasionally someone will pose a question about Supreme Court practice to me that deals with an issue I haven’t examined. Recently I had one such interaction with John Elwood of Vinson & Elkins. John asked if I had looked at applications for extensions of time to file petitions for writs of certiorari. Because I hadn’t looked at this issue in any detail before, I decided to bring a quantitative understanding of the practice to this post.

Putting the material together to file a petition for a writ of certiorari to the Supreme Court is no small endeavor. Compounding the time involved, parties often bring on experienced counsel to take over cases pending possible Supreme Court review. With filing requirements creating specific parameters for when cert petitions must be filed, counsel may find themselves under the gun to file in a timely manner. To circumvent these requirements, counsel may request certain time extensions to file. This post takes a look at several aspects of these requests, namely: who files them, how the justices respond and what these applications for time extensions contain.

The Rules of the Court create the time-specific filing requisites. Rule 13 contains the initial requirement that petitions must be filed “within 90 days after entry of the judgment.” Rule 13.5 then adds, “For good cause, a Justice may extend the time to file a petition for a writ of certiorari for a period not exceeding 60 days.” The Supreme Court requires attorneys submitting applications for extensions to establish the “basis for jurisdiction in this Court, identify the judgment sought to be reviewed, include a copy of the opinion and any order respecting rehearing, and set out specific reasons why an extension of time is justified.” Rule 30, entitled “Computation and Extension of Time,” contains additional information. Specifically, it states that:

An application to extend the time to file a petition for a writ of certiorari … shall be made to an individual Justice and presented and served on all other parties as provided by Rule 22[, which requires the application to be “addressed to the Justice allotted to the Circuit from which the case arises”]. Once denied, such an application may not be renewed.

These filings are not at all unusual. Looking at one randomly selected swath of time between December 4-12, 2017, 42 applications for extensions were filed prior to cert petitions. Although the maximum amount of time one can request is 60 days, not all petitioners request the entire amount of time. Here is an example of an application filed by experienced appellate attorney Shay Dvoretzky of Jones Day. The application for a month’s extension was granted but amended to one day less than the time requested.

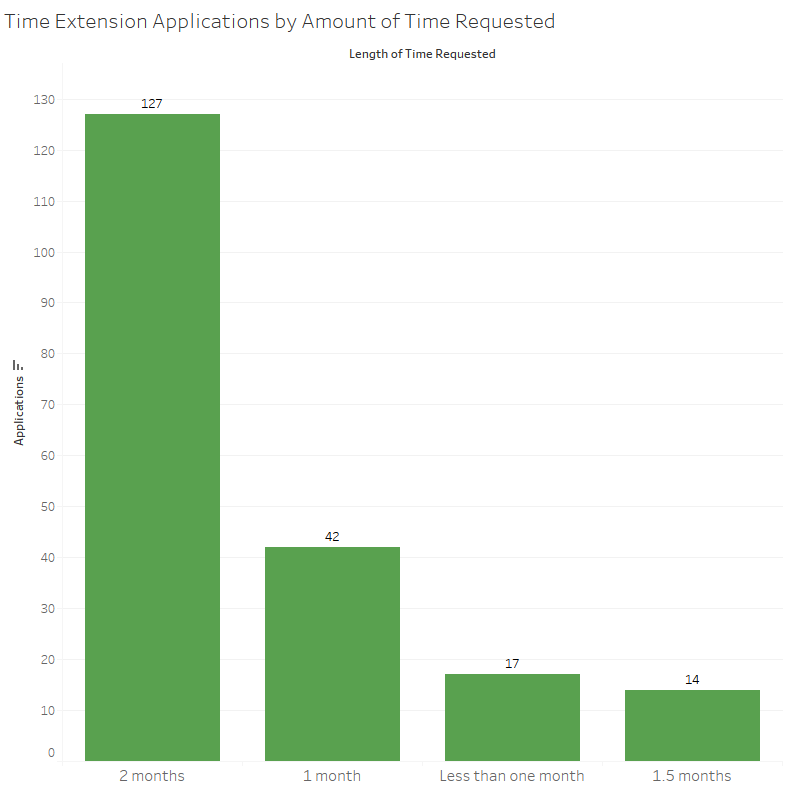

For the data in the post, I started with a random sample of 200 applications from the 2015 through the 2017 Supreme Court terms. First, I looked at the amount of time requested in the applications. The applications are sorted into the closest category if the requested time is in between two of them.

Note that the majority of the requests are for the maximum allotted time. A substantial minority of applications asked for less than the maximum amount of time, though. Why? In theory an attorney could craft a “good cause” argument for a more limited extension.

Although the justices are responsible for applications based on their allotted circuits, this does not necessarily lead to an even division of labor.

Justice Anthony Kennedy is assigned to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit and is thus responsible for the largest and most populated geographic region. He received the most applications, followed by Chief Justice John Roberts, who is responsible for the U.S. Courts of Appeals for the 4th, District of Columbia and Federal Circuits, and Justice Clarence Thomas, who is responsible for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit.

Now that we have a sense of the terrain for these applications, we can take a look at the justices’ responses. The justices responded to several applications by shifting the deadline to a few days before or after the requested date. This type of response most likely relates to the Supreme Court’s logistical concerns and not to the merits of the applications.

Of the 200 applications, 35 (17.5 percent) were denied or resulted in extensions that were at least a week below the requested time. Several justices disproportionately denied applications. In fact, only three justices denied applications in this set in their entirety. Of those three justices, Kennedy denied 12, Justice Antonin Scalia six, and Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg one.

More justices got into the action of granting applications, but for less time than requested. The breakdown of these is as follows.

Kennedy also led in this category, along with Justice Samuel Alito. Justice Neil Gorsuch was not far behind. Most of these amended extensions were given for one month instead of the two months requested. As both data points suggest, Kennedy is the most likely justice to deny or amend such extension applications, so those filing in the 9th Circuit should take care to provide good reasons for any requested extensions.

I dug deeper into a separate sample of 50 applications to understand their content. First, I looked at who files these applications and was met with some surprises. The following figure tracks the firm or group associated with each of the 50 applications in which this was made clear in the application.

Pro-se applications (filed on an applicant’s own behalf) were by far the largest group. Following these and other small law offices, firms with experienced attorneys also placed highly in this figure. Several of the attorneys of record on the applications are well known in Supreme Court circles. These include Mayer Brown’s Andrew Pincus, Stanford Supreme Court Litigation Clinic’s Jeffrey Fisher and Kirkland & Ellis’ Paul Clement. Other notable names on this list of 50 random applications include University of Texas’ Steve Vladeck, Jones Day’s Gregory Castanias, Latham & Watkins’ Gregory Garre and MacArthur Justice Center’s Amir Ali.

Of these 50 applications, four were met with grants that provided less than the time requested. (One applicant received an additional week, likely related to scheduling surrounding the holiday season.) Only one of these amended grants was from a pro-se filer, while the other three were from attorneys backed by big-name firms or groups. This at a minimum implies that an attorney’s place of practice is not the only variable the justices examine when deciding on these applications.

But what do these applications contain? I ran topic modeling software across the sections of these 50 applications relating to the rationale for extensions. This led to five sets of key words that help explain the types of requests made in the applications. The key words are as follows:

- Petition; certiorari; argument; writ; oral; reply; date

- Time; issues; current; complex; preparing; retained; attorneys

- Court; additional; record; circuit petitioner; states; supreme; review; appellate; filed

- Counsel; case; due; extension; prepare; undersigned; day; recently; holidays

- Including; file; appeals; law; applicant; state; pending; full

These key words help clarify that common justifications for the extension requests include other obligations before the petition’s original deadline date, holidays or break periods, case complexity and differently retained counsel at the Supreme Court level. Such explanations by no means secure granted applications in every instance, but they do give a sense of the reasons behind such requests.

Although this is only a small part of Supreme Court practice, successful applications may allow for improved petitions, while denied applications may result in cert petitions that are incomplete or less polished, reducing the likelihood that those petitions will be granted.

This post was originally published at Empirical SCOTUS.