SCOTUS FOCUS

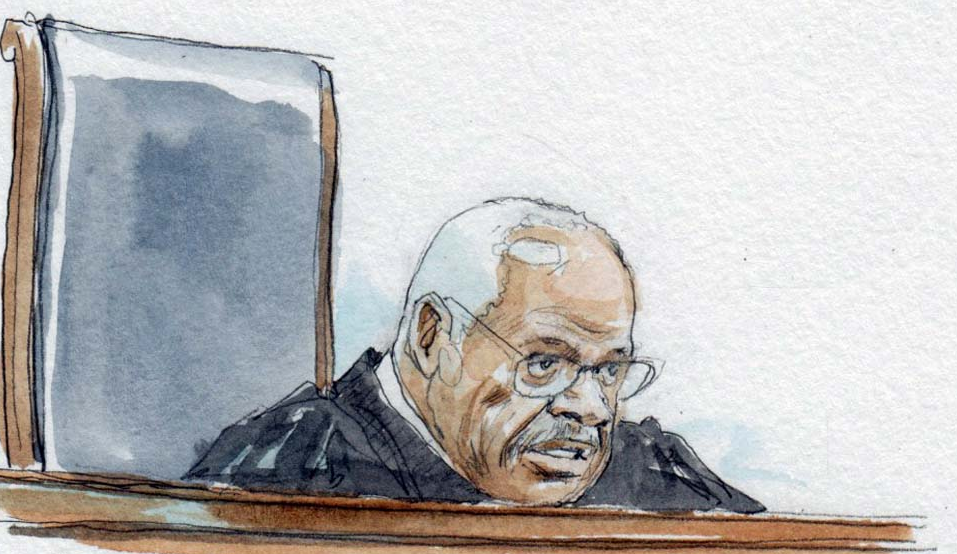

John Roberts is the chief. But it’s Clarence Thomas’s court.

on Oct 2, 2022 at 7:00 pm

When the Supreme Court returns to the bench on Monday for its first oral arguments of the new term, Justice Clarence Thomas almost certainly will ask the first question.

Thomas, who was appointed in 1991, is the court’s longest-serving justice and was for many years its most taciturn member. He famously went a decade without asking a single question. But when the court tweaked its argument format during the pandemic, Thomas began speaking up. He now interrogates the lawyers during nearly every case, often marking the terrain on which the case will be fought.

The other justices have even agreed to defer to Thomas at the start of each argument before jumping in themselves. The rationale is that Thomas, a stickler for politeness, dislikes interrupting the advocates or his colleagues. But it’s hard not to view the arrangement as symbolic of Thomas’s remarkable ascendance. Long considered an outlier on the court’s right flank, Thomas is now the intellectual leader of a conservative transformation that the six Republican-appointed justices are ushering into American law.

Few would have predicted it. Perhaps not even Thomas himself. In his second term, he boasted that he was “proudly and unapologetically irrelevant and anachronistic.” Back then, his commitment to originalism — the idea that the Constitution’s language should be interpreted solely according to how the words were understood when they were written — made him an ideological oddity, even among many conservatives. And his no-compromises approach alienated moderates like former Justice Sandra Day O’Connor.

Now, as he enters his 32nd term, his critics surely still see him as anachronistic, but he couldn’t be more relevant. Lower courts, elite appellate law firms, and Republican congressional offices are stocked with former Thomas clerks. Under President Donald Trump, no other justice had as many clerks appointed to the federal judiciary or to senior administration positions.

And of course there’s his wife, Ginni, who has tried to establish her own sphere of influence. She lobbied top Trump officials and state lawmakers to overturn the 2020 election — an effort that landed her before the Jan. 6 committee on Thursday. Thomas has stayed mum on his wife’s activities, and even the staunchest critics of the Thomases don’t expect the revelations about Ginni to erode Clarence’s influence.

That’s in part because many judges (including several other justices) now consider originalism to be the default mode of constitutional interpretation, and even non-originalists frequently employ its history-focused methods. It’s become commonplace at the Supreme Court to lean on obscure 19th-century documents (even ahistorical ones) and appeal to the nation’s deep-seated “traditions.”

To paraphrase Justice Elena Kagan, we’re all Thomists now.

If the 74-year-old justice is reaping a bounty, it’s because he’s been planting seeds for decades. In particular, three issues have long motivated Thomas above all others. The first is guns. The second is rights. The third is race.

On guns, Thomas pioneered a robust interpretation of the Second Amendment before it became conservative dogma. As a justice, he first floated the idea that the amendment guarantees a “personal right” (his emphasis) to own firearms in a solo concurrence in 1997. It took 11 years for five justices to adopt that position in District of Columbia v. Heller — at least as applied to guns kept in the home. Thomas wasn’t satisfied, though. In the years after Heller, he urged the court to take up more gun cases and further expand the amendment’s scope. When the court turned down those cases, Thomas wrote dissent after dissent, castigating his colleagues for treating the Second Amendment as a “constitutional orphan” and a “disfavored right.”

Earlier this year, he finally prevailed. In his majority opinion in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen — probably the most important opinion Thomas has ever written — he extended the right first recognized in Heller beyond the walls of the home, so the Second Amendment now protects individuals who wish to carry concealed handguns in public. Most significantly, he enshrined originalism as the legal test for analyzing gun-control measures. Rather than looking at contemporary evidence about gun violence, courts must now strike down any gun restriction unless an “analogous” regulation existed centuries ago.

If Thomas rescued gun rights from the constitutional orphanage, there is another, broader class of rights that he believes should be sent there instead: the bundle of “substantive-due-process” rights that are not explicitly listed in the Constitution but that nonetheless have been deemed fundamental to a free society. Conservatives and liberals largely agree with the premise of substantive due process, though they fiercely disagree on the specific rights that make it up. (Conservatives invoke certain economic rights; liberals invoke the rights to privacy and bodily autonomy.) Thomas, however, rejects the premise altogether. For three decades, he has argued that the whole doctrine is an oxymoron.

In Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the court eliminated the most contentious right under substantive due process: the right to obtain an abortion. Justice Samuel Alito’s opinion didn’t abandon the doctrine altogether. But his history-focused assessment of the right — an approach that is textbook Thomas — will sharply curtail the doctrine in other areas. And Thomas, in a concurrence, laid the groundwork for overturning the rights to contraception and same-sex marriage.

That leaves the matter of race. Here, too, Thomas’s views are unorthodox, even when compared with his fellow conservatives. Today’s court watchers may be surprised to learn that, as a young man, Thomas was immersed in Black nationalism. The political scientist Corey Robin has persuasively shown that Thomas’s worldview is rooted in that experience. He grew up in rural Georgia during Jim Crow, became a self-described “radical” devotee of Malcolm X, and came to view liberal social policies as white paternalism.

Nowhere is this more apparent than on the issue that likely will define the upcoming Supreme Court term: affirmative action in higher education. Other conservative critics of affirmative action argue that society must transcend race by adopting colorblind policies. And they say the practice is unfair to white students (or Asian American students, as the challengers contend in the two cases now before the court). Not Thomas. He views affirmative action as a “benighted” form of “racial experimentation” perpetrated by the white ruling class against Black people, including himself.

In his 2003 dissent in Grutter v. Bollinger, Thomas accused the court’s majority of ignoring “growing evidence that racial (and other sorts) of heterogeneity actually impairs learning among black students.” The court upheld affirmative action in that case, in a landmark opinion by O’Connor. Now, opponents of affirmative action are asking the newly conservative Court to overturn Grutter and effectively outlaw race-conscious admissions nationwide.

The cases will be argued on Halloween, but the court’s opinion probably won’t drop until the end of the term in June, possibly on its last day. Its most likely author: Clarence Thomas, the justice who now asks all the first questions and, more often than not, gets the last word.

This column was originally published on Sept. 29 in National Journal and is owned by and licensed from National Journal Group LLC.