ARGUMENT ANALYSIS

Justices wrestle with mootness and intergovernmental immunity in Hanford workers’ comp case

on Apr 20, 2022 at 9:46 am

It might not be easy to get to the merits of United States v. Washington. A funny thing happened on the way to oral argument: The state of Washington modified the 2018 workers’ compensation law at the center of the case, raising the prospect that there is no longer a live dispute for the justices to resolve.

The state’s old law, H.B. 1723, was aimed at federal contract workers who got sick after helping clean up the Hanford nuclear site in southern Washington. It created a presumption that certain conditions suffered by those workers were “occupational diseases.” The new law, S.B. 5890, expanded the presumption beyond federal workers; the presumption now applies to “all personnel working at a radiological hazardous waste facility.” Because the merits of the case concern whether Washington can constitutionally discriminate against federal contractors by utilizing a causation standard making it easier for those employees to obtain workers’ compensation awards (with the federal government as de facto self-insurer of the awards), a problem of mootness arose. Discrimination — if that is what it was — ceased to exist as soon as the new law took effect on March 11, 2022.

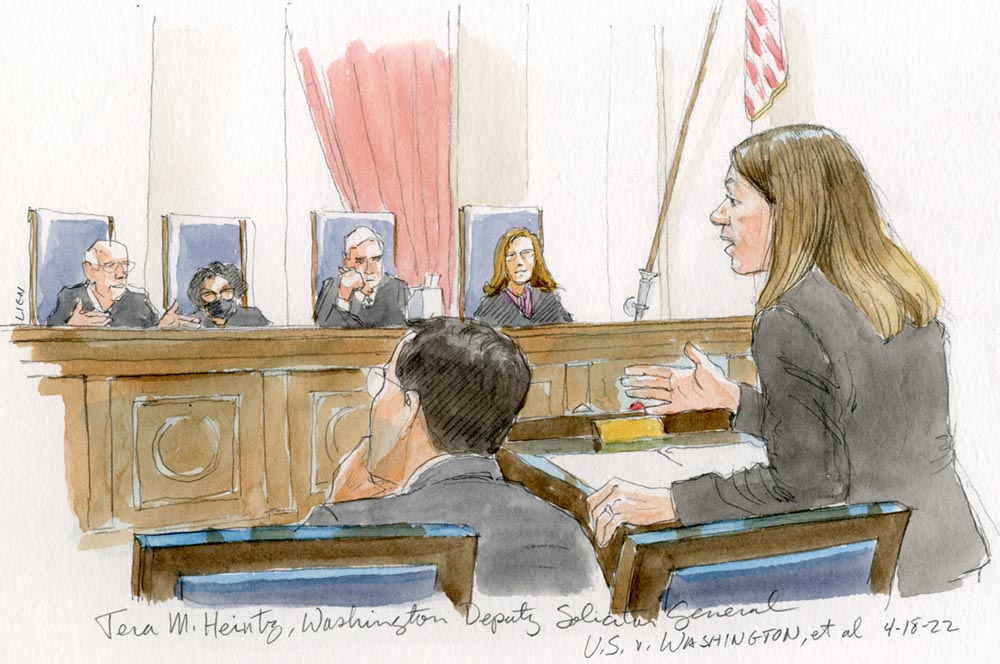

Still, as discussed at length during Monday’s argument, the two statutes might not be coextensive in the benefits they offer to covered workers. As Justice Clarence Thomas observed, some statutory beneficiaries under the old law might prefer its protections. Some workers engaged in arguably less hazardous work may have been covered under that law but not under the new law. If some workers’ compensation claims remain live under the old law, then the case might not be moot after all. But Tera Heintz, arguing for Washington, assured the justices that the new law eliminates that possibility because it applies retroactively. The result, Heintz said, is that the 66 pending claims and 140 closed claims are now governed exclusively by the new law. To the extent the United States seeks declaratory and injunctive relief from the old law, no such relief could be available.

Malcolm Stewart, arguing for the federal government, responded that, while it was uncertain a decision invalidating the old law would “ultimately produce any financial benefit to the United States,” the case is not moot “so long as there is a reasonable possibility that such a benefit will ensue.” How could there be such a reasonable possibility? For one thing, Stewart said, Washington’s argument that the new law will necessarily be given retroactive effect by the Washington courts is speculative. Furthermore, the burden to establish mootness after the Supreme Court agrees to hear a case is very high — and Washington’s prediction that the new law will be given retroactive effect based on a 1935 Washington state case might not fit the bill. In this context, Justice Elena Kagan was moved to wonder if the case should be certified to the Washington Supreme Court for an authoritative opinion on the retroactive application of S.B. 5890 under Washington law. In response, Stewart argued that the very suggestion of seeking certification highlighted the kind of uncertainty tending to demonstrate that Washington could not meet the high bar of establishing mootness.

Kagan then asked if the United States would have pursued the case had Washington amended its law before the federal government’s cert petition had been due. Stewart expressed doubt. The parties tiptoed around the question of whether the Washington legislature had strategically amended the old law to evade review by the court. Heintz observed that the legislature meets relatively infrequently and had acted entirely in good faith.

On the merits, the advocates substantially renewed the positions they had taken in the briefs. Justice Sonia Sotomayor pressed Stewart on the scope of Congress’ waiver of immunity for state workers’ compensation liability. “Opposing counsel points to a number of statutes that very clearly say you can’t discriminate against the federal facility or federal employees — they have very express language about being treated equally, which this statute doesn’t,” Sotomayor said. “Why doesn’t that show us, if it’s an ambiguity as to the scope, that the scope is as broad as the language supports?” This renewed Washington’s point that when Congress wants to limit the federal government’s waiver of immunity it has done so in narrower terms.

Citing Federal Aviation Administration v. Cooper, Stewart argued that when Congress waives immunity the scope of the waiver is always subject to a plain-statement rule. Whatever the scope of the immunity, he continued, nothing in the waiver authorizes facial discrimination against the United States. Furthermore, he said, no state had attempted to openly discriminate against the United States under the workers’ compensation waiver during the roughly 80 years of the waiver’s existence. Chief Justice John Roberts met this point by observing that “there aren’t very many places like Hanford, … where you have a situation where basically anybody there is certainly subject to great concern.” Stewart conceded, “I don’t know of specific analogues to Hanford.” This exchange echoed undertones from Washington’s core argument that its actions were a necessary reaction to the uniquely dangerous Hanford worksite and were not an attempt to target the United States.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett seemed most interested in the United States’ argument that the operation of the waiver contemplated the executive rather than legislative branch of state government. Under 40 U.S.C. § 3172, “the state authority charged with enforcing and requiring compliance with the state workers’ compensation laws and with the orders, decisions, and awards of the authority may apply the laws to all land and premises in the State which the Federal Government owns or holds by deed or act of cession.” This “doctrinal hook,” as Barrett put it, might be read as authorizing a state administrative workers’ compensation agency to apply preexisting legislatively-enacted law “in the same way and to the same extent as if the premises were under the exclusive jurisdiction of the State in which the land … [is] located.” Such a reading avoids a conclusion that a state is locked into the 1936 law because amendment would expand the scope of congressional waiver. But the strategy seems wrong: Administrative agencies are required to apply law in accord with state statutes and could not independently do otherwise. Section 3172 probably unartfully applies to a state’s overall workers’ compensation system.