ARGUMENT ANALYSIS

Justices search for the line on “use” of a locomotive

on Mar 30, 2022 at 2:23 pm

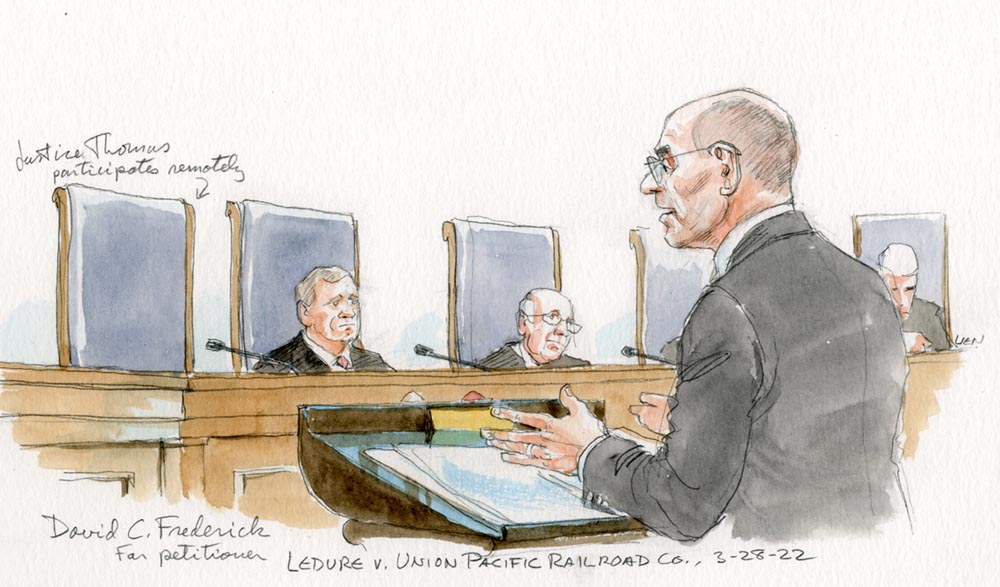

The Supreme Court heard argument on Monday in LeDure v. Union Pacific Railroad Company. The case involves the Locomotive Inspection Act, a federal statute that requires railroads to regularly inspect and implement safety measures for their locomotives. Notably, the act applies only to locomotives that are in “use” (or “allowed to be used”) on the railroad’s line. Everyone agrees that locomotives are in use when they are in motion, or when temporarily stopped on the tracks amid an active journey. But what about when a locomotive is parked at a railyard and is not ready to move imminently?

The answer to that question, which the justices faced on Monday, has tort-liability consequences: A railroad that violates the inspection law is strictly liable for any injuries suffered by its employees. Bradley LeDure, a former Union Pacific engineer, fell on a locomotive while it was parked in a railyard in Salem, Illinois. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit held that the locomotive was not in “use” at the time of LeDure’s injury because it was stationary and needed to be serviced before continuing on its journey.

David Frederick, arguing for LeDure, urged the justices to give the act a broad reading: A locomotive is in use whenever the railroad is “employing it for the railroad’s purposes.” That test, Frederick explained, readily covers locomotives that are sitting on the tracks; those engines stand ready to be deployed for various purposes, such as providing backup power or moving railcars around the yard. Frederick emphasized, however, that his test was not unlimited. A locomotive is not in use, he explained, when being housed in a dedicated repair shop, or if the railroad has withdrawn the locomotive from service by making it “inoperable” (by disconnecting its battery and draining the brake fluids).

Frederick relied heavily on precedent interpreting a related statute, the Safety Appliance Act, which uses the same key term and has long been interpreted to regulate even stationary railcars. Chief Justice John Roberts, however, immediately expressed skepticism about the claimed relationship between the safety laws. The Safety Appliance Act, Roberts noted, regulates all railcars, not just locomotives. And whereas most railcars are designed to passively hold goods and people, the “primary purpose” of a locomotive is “to move.” Justice Brett Kavanaugh picked up on this theme, telling Frederick, “the ordinary understanding of ‘use’ is not great for you.”

Colleen Sinzdak, who argued for the United States in support of LeDure, drew similar skepticism about the ordinary meaning of “use.” Justice Samuel Alito, for example, suggested that regular people (if surveyed) would never come up with the same “highly refined rule” advanced by LeDure and the government — that a locomotive is in use even when sitting idle on the tracks.

The chief justice and others also pushed back on assertions by Frederick and Sinzdak that a narrower definition of “use” would leave a “safety gap.” Roberts noted that the Federal Employers Liability Act allows a railworker to recover for negligence by his employer, regardless of whether the Locomotive Inspection Act applies. And Alito and Justice Sonia Sotomayor pressed Frederick on why it made sense to impose strict liability when a locomotive was shut down on the tracks but not in a repair shop, given the dangers presented in both locations.

Justice Clarence Thomas participated remotely, in his first argument back following his hospital stay last week, but was as active as ever. Thomas even offered a personal example to test the limits of Frederick’s and Sinzdak’s theories: When Thomas drives his motor coach across the country — as he is known to do during the court’s summer recess — he tows his car behind it. If the car’s brakes and lights still operate while being towed, Thomas asked, is the car in use? Frederick answered yes, emphasizing that, during the journey, no one else can put the car to use. But Thomas seemed unconvinced, explaining that “the point of the car is not to be hauled behind the motor home.”

J. Scott Ballenger arguing for Union Pacific Railroad. (Art Lien)

Scott Ballenger, arguing for Union Pacific, criticized LeDure and the government for “rewriting the statute” — illustrating his accusation with their insistence that a railroad must take specific technical measures like draining brake fluid to halt a locomotive’s “use.” Ballenger proposed an alternative test, in which a locomotive is in use only while actually moving or temporarily stationary on the tracks during a journey (the latter situation akin to “an automobile stopped at a stoplight”). Ballenger also offered a “new observation” that he admitted “isn’t in the briefs”: If LeDure were correct that even stationary locomotives are in use, Ballenger argued, it would effectively nullify the Safety Appliance Act’s “safe harbor” for moving defective locomotives to a repair shop (which LeDure and the government invoked to downplay the practical consequences of their broad interpretation). “A safe harbor is worthless,” Ballenger explained, “if the locomotive is subject to the exact same civil penalties whether it moves the car or not.”

Several justices seemed troubled by the logic and consequences of Union Pacific’s test. Justice Elena Kagan observed that imposing safety requirements before a locomotive begins its journey seems entirely sensible; the very purpose of the Locomotive Inspection Act is to require precautions “before the train is moving.” Ballenger responded that restricting the statute’s application to active locomotives would merely “give the railroad a chance to get [them] in safe condition” without fear of liability. Sotomayor and Kavanaugh questioned whether Ballenger’s proposal adequately protected worker safety, with Sotomayor observing that “locomotives by definition are more dangerous than railroad cars,” and Kavanaugh highlighting that a large share of accidents occur on stationary locomotives.

In a field crowded with creative hypotheticals — including one from Roberts about a locomotive used only to advertise the railroad, and another from Alito about a locomotive converted into a restaurant — Breyer perhaps earned first prize with a hypothetical based on a famous children’s story, The Little Engine That Could. The protagonist there stalled near the top of a hill, building courage to make a final charge. When motionless, Breyer asked, was the Little Engine in “use” under Union Pacific’s theory? Ballenger answered yes: It is “applying tractive power even if it’s having a hard time getting up the hill.” For Breyer, however, the prospect of a “tractive power” test confirmed that the concept of “use” is so inherently context-dependent that the court would be better off taking the “common law approach” of resolving just this particular case, rather than attempting to determine the word’s meaning for all time.

Although justices’ questions are not always predictive of their votes, the case seems unlikely to produce unanimity. Several justices seemed skeptical of LeDure’s position; several others seemed to lean against Union Pacific; and Justice Neil Gorsuch asked no questions. Justice Amy Coney Barrett is recused, putting in play the possibility of a four-to-four division. A tie would affirm the decision of the 7th Circuit — an outcome known as affirmance by an equally divided court — but would not produce a precedential opinion.