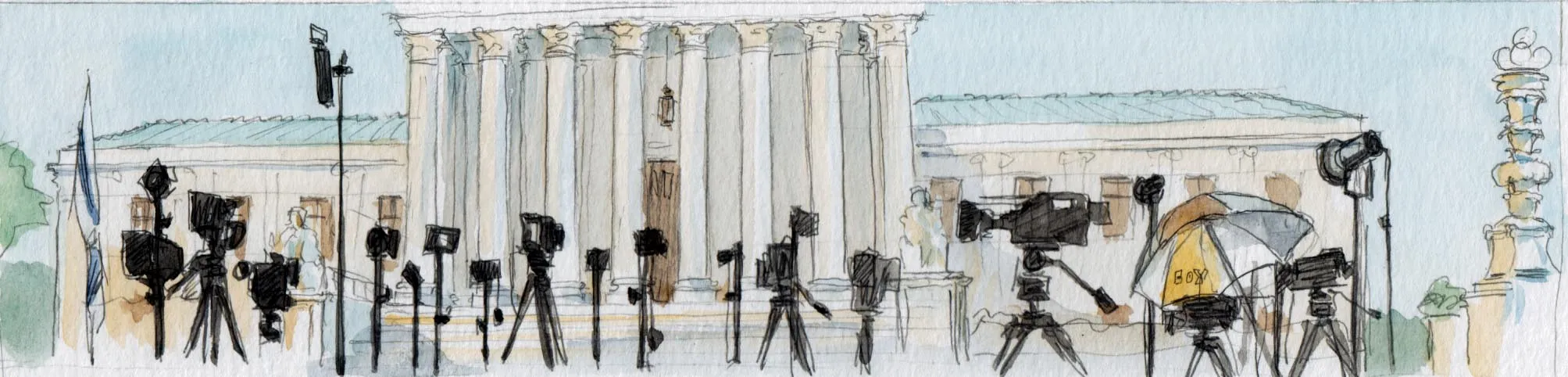

Jackson should tell the Senate she’s pro-cameras, but she won’t

[Editor’s note: Cameras remain prohibited during sessions of the Supreme Court, but some lawmakers and advocates want to change that. We invited experts on each side to weigh in on the current state of the debate. The other piece in this series can be found here.]

Gabe Roth is the executive director of Fix the Court.

Every time there’s a Supreme Court confirmation hearing, at least one senator on the Judiciary Committee asks the nominee his or her views on cameras in the courtroom.

But like everything else during these carefully choreographed hearings nowadays, nominees typically give a boring, noncommittal answer in response. We can call this the “Cameras Corollary,” to the so-called “Ginsburg Rule,” where a nominee offers “no forecasts, no hints” about how he or she views a judicial issue before ascending to the high court.

Case in point: then-Judge Amy Coney Barrett told the committee in 2020, “I would certainly keep an open mind about allowing cameras in the Supreme Court,” echoing similar sentiments from then-Judges John Roberts, Sonia Sotomayor, Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh in years prior. I expect Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson to give a similar answer when asked later this month. (Then-Solicitor General Elena Kagan’s enthusiastic endorsement was and remains an aberration, though it seems that Kagan changed her position after confirmation.)

This trend is maddening.

Just like there’s not really a Ginsburg Rule, there shouldn’t be a Cameras Corollary. The public deserves to know if a nominee trusts the public to see with our own eyes, and in real time, what goes on during Supreme Court oral arguments.

Arguments against cameras in the court assume the worst from our justices and the attorneys who argue before them — that if court proceedings were filmed, these legal giants would turn either into toddlers, unable to resist the opportunity to throw a tantrum, or politicians on the campaign trail, playing for an applause line. That would not happen.

We know this because oral argument audio has been livestreamed for the past two years, and nothing of the sort has occurred — nor did any justice or attorney act in such an unprofessional manner during the seven decades prior in which argument audio was recorded though released on a delay. (If you’re worried about what oral argument spectators might do, I can direct you to the dozens of state supreme courts and foreign supreme courts that aren’t constantly being interrupted during their televised oral arguments.)

Just like none of the SCOTUS nine has done anything during the livestream that suggests they’d go rogue with video, Jackson has herself displayed a calm comportment during her time on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, where arguments are livestreamed, albeit also audio only.

It’s true that the members of the House of Representatives and Senate at times behave poorly when the cameras are rolling. But they are incentivized to act that way — to stand out from the crowds of 435 or 100. That’s how they get name recognition, donations, and even votes. All Supreme Court justices have some name recognition, at least in the circles where it counts. And they never seek donations or votes (at least they shouldn’t).

It’s a shame that among federal appeals courts only the U.S. Courts of Appeals for the 2nd, 3rd, 7th, 9th and 11th Circuits have ever allowed cameras over the years. But that would change if a bill introduced in Congress last year becomes law.

Last summer, for the first time in a decade, the Senate Judiciary Committee advanced a bipartisan bill that would permit video recording and livestreaming of Supreme Court oral arguments (the Cameras in the Courtroom Act) and another that would permit video in the lower federal courts (the Sunshine in the Courtroom Act).

Given who the lead sponsors are — the committee chairman and no. 2 in the Senate, Democrat Dick Durbin of Illinois, and the committee’s top Republican, Chuck Grassley of Iowa — one might assume the bills would have some chance of making it to, and advancing through, the Senate floor, moving to the House and becoming law. They will not.

My sources indicate that Durbin and Grassley will not be using any more political capital on this issue. The bills will die before getting a floor vote, just as they did in 2011, the last time they passed through committee.

My best guess as to when cameras will make their way into the Supreme Court is after the older generation of justices — Stephen Breyer, Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, and Roberts — leaves the bench. As far as the rest: we know Sotomayor and Gorsuch both support expanded civics education, which video-recorded arguments would plainly bolster. Kagan allows live video for most of her public events. Kavanaugh sat on the first-ever D.C. Circuit panel that permitted live audio, in October 2017, so that bodes well for live video. Barrett was on the panel, in February 2020, for one of the few 7th Circuit arguments that was video recorded.

And Jackson, a Gen Xer like the three Trump nominees, appears to be quite comfortable in front of a camera. The public will get to see that level of comfort on display on March 22 and 23 during her confirmation hearings.

Unfortunately, it may be a couple of decades before the vast majority of the general public has an opportunity to see her perform her high court duties.

Posted in Focus on cameras at the court