Divergent views on text and history as justices ponder war powers and sovereign immunity

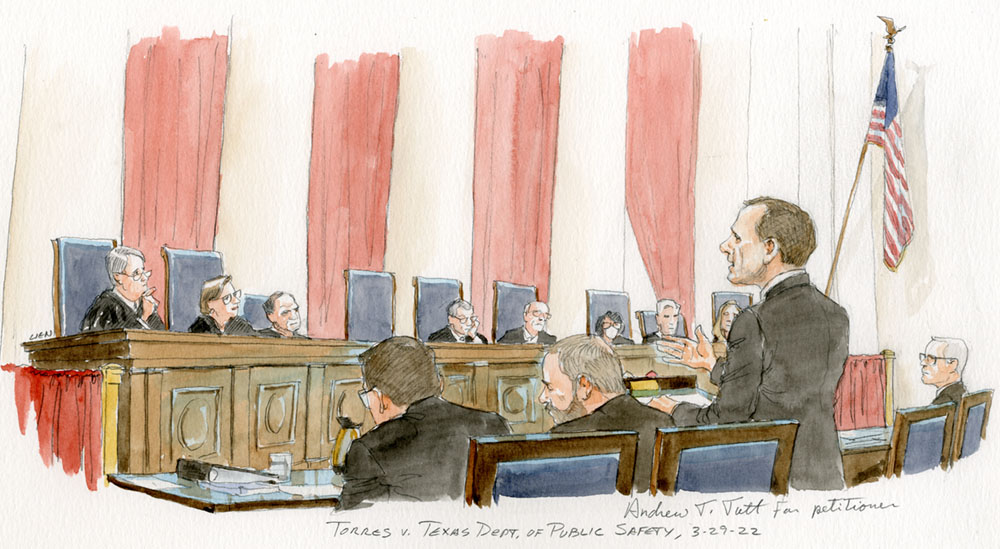

The Supreme Court heard oral argument on Tuesday in Torres v. Texas Department of Public Safety, with Justice Clarence Thomas participating remotely after his hospital stay last week. The case was brought by a military veteran against his state-agency employer under the federal Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Rights Act of 1994. Torres alleged that, contrary to USERRA, the department refused to reemploy him in a job comparable to the one he had held prior to being called up from the Army reserves. The department responded that as a state agency, it was immune from suit, and a Texas court agreed and dismissed the suit.

As explained in the case preview, the precedents governing state immunity from suit are complex and not always consistent with one another. At stake in this case is whether Congress can use its constitutional war powers to subject states to suits by private individuals.

Prior precedent (including Seminole Tribe of Florida v. Florida) held that Congress could abrogate state sovereign immunity when acting under Section 5 of the 14th Amendment, but not when acting under many of its Article I powers. The courts rationale in those cases was that the original meaning of Article I gave Congress no power to abrogate immunity but the original meaning of Section 5 did so. But the court has also held that the states themselves waived their immunity from certain types of suits when they ratified the Constitution, based on the states understanding of the plan of the [constitutional] Convention that is, based on their understanding of the structure of the Constitution itself.

Several justices struggled on Tuesday with the difference between congressional abrogation and state waiver. Justice Elena Kagan asked why there were two separate buckets for cases governing the elimination of state sovereign immunity. She suggested that whether the states understood some part of the Constitution to waive their immunity or whether they understood it to give Congress the power to abrogate their immunity looked at the same [historical] sources. Chief Justice John Roberts agreed that earlier cases drew the distinction, but pressed Assistant to the Solicitor General Christopher Michel on the nature of the distinction and what consequences follow from it. Justice Amy Coney Barrett wondered whether the Seminole Tribe case would have come out differently had it been argued as a waiver case rather than as an abrogation case. And Justice Brett Kavanaugh began a question to Texas Solicitor General Judd Stone by conceding that our precedent in this area, as a whole, … points arguably in different directions.

The justices also struggled to make sense of the precedents regarding which suits can be brought against states and which cannot. Justice Neil Gorsuch asked how the Indian commerce clause was different from the war powers clauses. Kavanaugh said it would be bizarre to allow suits against states under the Family and Medical Leave Act and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, among others, but not under statutes enacted pursuant to Congress war powers, where the national interest is at its apex as compared to those other areas. Kagan asked in what world could it be a sensible result to say states can be sued on the basis of the eminent domain clause but not on the basis of war powers?

As expected, much of the questioning focused on historical sources, especially Alexander Hamiltons writings. Hamiltons contributions to the Federalist Papers were cited and sometimes quoted seven times by the advocates and five times by the justices. Most of the attention was focused on Federalist No. 23 (on the federal governments war powers), but No. 32 (on necessary limitations on state sovereignty), and No. 81 (on the powers of the federal judiciary) also received some attention. Justice Stephen Breyer even quoted a couple of lines from the musical Hamilton. And when Andrew Tutt, representing plaintiff Le Roy Torres, encourage[d] the justices to read the Federalist Papers, Gorsuch retorted that I think you can safely assume this bench will and has read a lot of things. Thomas, whose historical methodology often differs from that of his fellow originalists even when agreeing with their conclusions, demurred, stating that he was not as enamored of Hamilton as some are.

It might seem from this extended discussion of historical understandings that, as Kagan said in her confirmation hearings, we are all originalists now. The arguments in this case, however, also highlighted two problems with that conclusion.

First, as many scholars have previously observed, historical analysis rarely gives determinate answers to questions about what the founding generation thought, intended, or understood even when that analysis is done by professional historians rather than by lawyers and judges. That indeterminacy was on full display during the argument, as different justices and different advocates invoked the same historical sources, and often the same quotations, to reach opposite conclusions. It is likely that, as in Alden v. Maine (an earlier state sovereign immunity case) and District of Columbia v. Heller (interpreting the Second Amendment), the majority and dissenting opinions in this case will rely on identical historical evidence.

Even more interesting was the interplay between two constitutional methodologies: originalism and textualism. Originalist judges seek to implement the original plain meaning of the Constitution, or of a statute, focusing on historical context. Textualists instead look only at the text whether of the Constitution or of a statute and ignore what its drafters might have had in mind.

Of course, textualism is no more certain to produce determinate results than is originalism. The most recent example from the Supreme Court is Bostock v. Clayton County, which held that the federal law prohibiting employers from discriminating because of a persons sex protected homosexual and transgender employees. Both Gorsuchs majority opinion and the two dissenting opinions purported to rely on the plain meaning of the statutory text, but came to diametrically opposed conclusions.

The oral argument in Torres produced a very interesting comparison between two committed textualists, Gorsuch and Kavanaugh. Gorsuch who had been laser-focused on the text and the text alone in Bostock kept asking questions about history: When did Congress first exercise its authority under the war powers to authorize individual suits against states, and why didnt it do so earlier? How is the history of bankruptcy suits different from the history of other suits against states? What is the meaning of certain early 19th-century precedent? He also dismissed the textualist arguments by telling Michel that I understand the textual commitments in the 14th Amendment, but, here, we’re being asked to adopt a view of implicit penumbras emanating from the … war powers.

Kavanaugh, who dissented in Bostock, kept bringing the advocates attention back to the text of the Constitution, which explicitly divests the states of any power over war, peace, or foreign relations. He told Michel, you’re relying on the raise-and-support-armies Clause, the text. You’re not relying on penumbra, I didn’t think. (Michel readily agreed.)

Finally, many justices seemed very concerned with the practical implications of this case. Gorsuch and Justice Samuel Alito were concerned that if Torres prevailed, then Congress could authorize myriad suits against states by claiming that it was acting under its war powers including suits for failing to fix potholes on interstate highways, because the interstate highway system was initially justified in part as necessary to the national defense.

Kavanaugh, Barrett, and Breyer seemed more concerned with the consequences if the department prevailed. Kavanaugh asked Michel, What’s the realistic problem that you foresee if you don’t prevail in this case? Barrett reminded Stone that USERRA was enacted in 1974 because states expressed their policy disagreements with the Vietnam War by refusing to hire or rehire returning soldiers. She asked him what should be done if we get involved in Ukraine and states say that we shouldn’t be, and so they use discrimination against veterans returning home to express their disapproval of our engagement? Kavanaugh echoed Barretts point, telling Stone that the ability to attract volunteers into the military is a practical argument, and you can just say that’s irrelevant if you want, but it’s an important overlay of what’s going on here. Breyer was even more emphatic:

This has the potential of being a pretty important case for the structure of the United States of America. The war power is not copyright, and it is not the Indian commerce clause. It is, and you know, as Lincoln said, will this nation long endure?

However the court decides this case and it is unlikely to be unanimous there will be much discussion of history and of text in all of the opinions. But under the surface, and perhaps even in the opinions, will lie questions of practicality and fairness. As Tutt eloquently summed up the case in his rebuttal:

Captain Torres went to war, and when he came home, he brought a piece of the war with him. And if he had been a member of the local sheriff’s department or a U.S. marshal or worked for any other employer, he would have been able to sue to vindicate his rights. But because he worked for Texas, he had no cause of action. The war powers do not countenance that result. It’s not right. We’re asking this court to make it right.

Posted in Merits Cases

Cases: Torres v. Texas Department of Public Safety