Arbitration clauses, prejudicial delays, and one justice’s contract-law “nightmare”

The current Supreme Court is undoubtedly pro-arbitration – but after Monday’s oral argument in Morgan v. Sundance, it appeared that it might nonetheless conclude that a party can lose the right to arbitrate by waiting too long to demand arbitration. At the same time, the justices seemed to differ over why that was, and what standard the court should adopt for future cases.

This case began when Robyn Morgan filed in Iowa federal court a wage-and-hour complaint on behalf of herself and similarly situated employees against Sundance, Inc., a Taco Bell franchisee. Sundance had included in Morgan’s job application an arbitration clause, which meant that the company could have immediately sought to put the litigation on hold, and to require Morgan to resolve her case through individual arbitration. Instead, Sundance began to litigate the case, first moving to dismiss Morgan’s complaint for reasons unrelated to arbitration, then filing an answer, then attempting to settle the case. Finally, about eight months after Morgan filed her complaint, Sundance moved to compel arbitration of Morgan’s claims.

The district court decided that by delaying, Sundance waived its right to demand arbitration. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 8th Circuit reversed that decision based on its conclusion that Morgan had not been prejudiced by the delay. Before the Supreme Court, Morgan is arguing that courts cannot adopt special, arbitration-specific waiver standards: If state law normally does not require a showing of prejudice to establish waiver of a contractual right — and she argues Iowa law does not — courts also should not require prejudice before finding waiver in the arbitration context.

This case mainly involves two sections of the Federal Arbitration Act. Section 2 directs that arbitration contracts are enforceable in federal court, except “upon such grounds as exist at law or in equity for the revocation of any contract.” Section 3 directs federal courts to stay litigation of any dispute that is covered by an arbitration agreement, “providing the applicant for the stay is not in default in proceeding with such arbitration.” Morgan primarily focuses on Section 2, which she argues requires that arbitration agreements be treated the same as other contracts. For its part, Sundance urges the court to start with Section 3, arguing that it was entitled to a stay in favor of arbitration because it was not in “default.” It further argues “default” occurs only when a party “violates a clear legal rule or causes prejudice” to the other party – a definition that Justice Elena Kagan suggested was “a bit made up.”

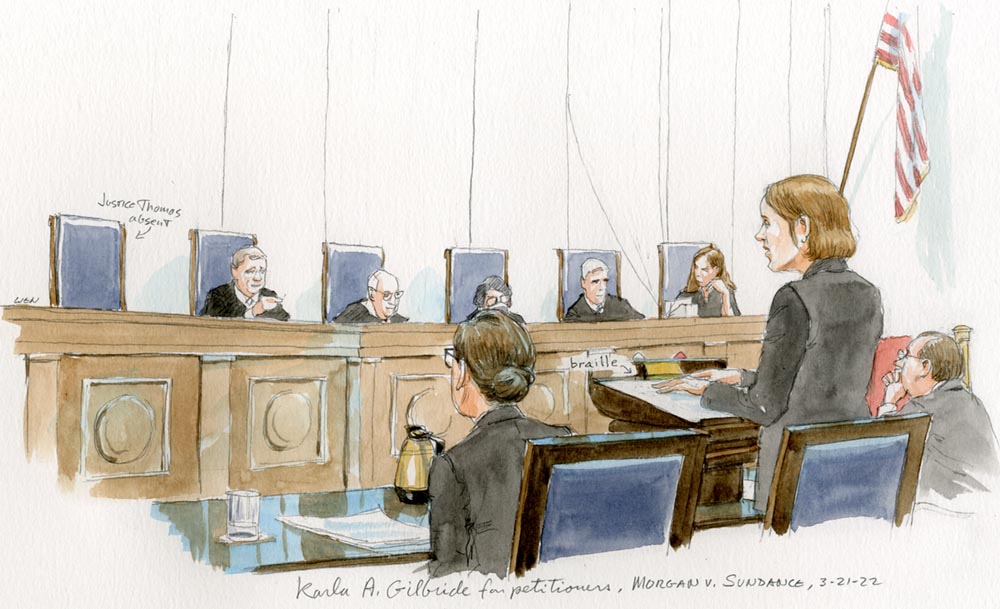

Much of the discussion during oral argument concerned whether and when to apply state contract law to questions arising under the FAA. For example, Kagan’s first question for Karla Gilbride, who was representing Morgan, was whether courts should look to state law to interpret the term “default” as it is used in Section 3; Justices Samuel Alito and Sonia Sotomayor later raised similar questions. Gilbride’s answer was that it depends what “default” refers to – contractual defaults should be analyzed under state law, while statutory defaults would be analyzed under federal law.

Gilbride also urged the justices to approach questions about the enforceability of arbitration contracts, which arise under Section 2, by applying state law. Several justices seemed to find this argument persuasive – Justice Stephen Breyer called it a “logical framework,”‘ and Alito called it “strong” and “cogent.” But some justices also seemed to think that synthesizing and applying state contract law could prove difficult. Breyer put this point evocatively, saying he “used to have nightmares about teaching a class” and having a student ask a question about “something I didn’t know,” and he asked Gilbride for a reading recommendation about contracts concepts “that would prevent me from getting into this nightmare.”

Breyer was not the only justice who seemed to have qualms on this point – Justice Neil Gorsuch proposed an alternate approach, based on federal civil procedure, that would have rejected the 8th Circuit’s prejudice requirement without resorting to state contract law: “Lord only knows what Iowa state law defenses are,” but “I think with some degree of certainty that waiver, whatever else it requires in federal court … doesn’t require proof of prejudice.” However, Gilbride reiterated that the FAA’s “substantive mandate” in Section 2 calls for the application of state law.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh also proposed an alternative approach to state law, asking Gilbride’s views on the approach adopted by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit to determine whether a party seeking to enforce an arbitration agreement is in default. As Kavanaugh described it, that approach involves “a presumption of forfeiture if you have not raised arbitration in the first responsive pleading.” Gilbride replied that this would be “a good model for this court to look to.”

Several justices also seemed interested in the consequences of either affirming or reversing the 8th Circuit. For example, Kagan asked Paul Clement, representing Sundance, whether affirming the prejudice requirement would allow “two bites at the apple,” because defendants would have a “free pass to litigate for a while.” Clement replied that the “prejudice inquiry is not so clear” as to provide a free pass. Other justices wondered whether eliminating the prejudice inquiry and directing courts to apply state contract law would work a “sea change,” or would risk inefficient litigation over the meaning of state law, and uneven outcomes. However, Sotomayor suggested that uneven outcomes, complexity, and delay can result either way, if companies are emboldened to carry out motions practice in court before pursuing arbitration, or if courts are inconsistent in determining whether parties have been prejudiced.

If there’s one thing that Monday’s argument revealed, it is that the justices do not relish the idea of having to take a deep dive into the nuances of Iowa contract law. This reluctance may lead a majority of the court to adopt Kavanaugh’s proposed approach – that is, adopting a presumption of prejudice when a party fails to invoke its right to arbitration right away. At a minimum, the court seems likely to put in place stronger guardrails to deter strategic delay in invoking arbitration.

Posted in Merits Cases

Cases: Morgan v. Sundance, Inc.