Justices signal narrow support for allowing equitable tolling of tax deadline

At the argument on Wednesday in Boechler v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, most justices seemed prepared to allow consideration of equitable tolling in tax collection due process cases so long as a decision is written narrowly and does not spill over to support equitable tolling for other tax deadlines.

The case arose after Boechler, P.C., a law firm, sent a petition one day late to request review in the U.S. Tax Court of an IRS notice of determination. The notice of determination, issued by the IRS Independent Office of Appeals after a collection due process hearing, had sustained a levy on Boechlers property to satisfy a $19,250 penalty. The case turns on Section 6330(d)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code, which states that a person may, within 30 days of a determination under this section, petition the Tax Court for review of such determination (and the Tax Court shall have jurisdiction with respect to such matter).

The question in Boechler is whether the statute bars a taxpayer who missed the deadline from asserting equitable tolling, which allows courts to excuse missed deadlines in some circumstances. Under applicable precedent, if the statute makes the 30-day time limit jurisdictional, then equitable-tolling claims are barred. The backdrop of Wednesdays argument also included the statute that requires specific grants of jurisdiction to the Tax Court, which is not an Article III court.

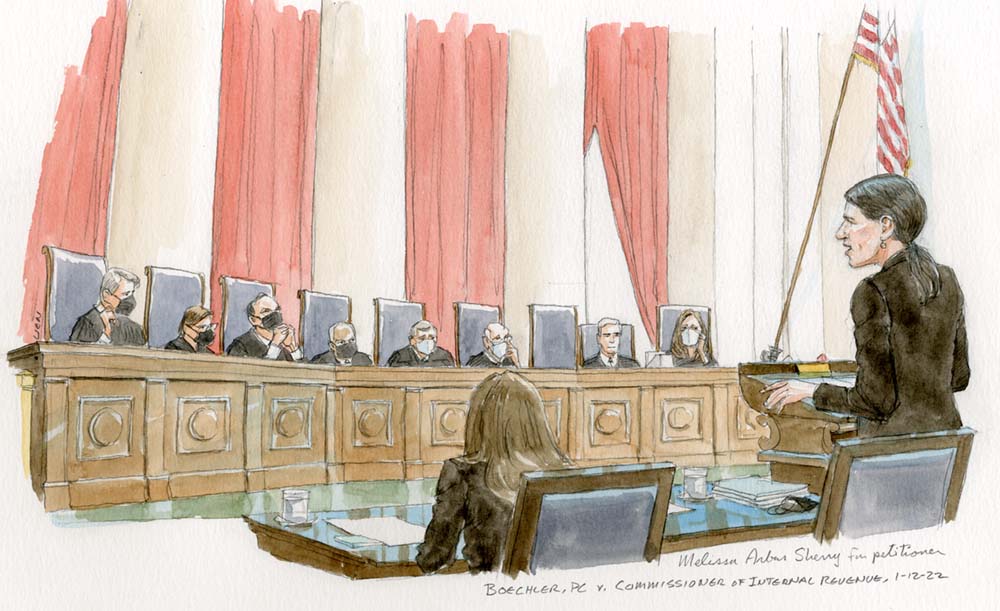

Advocates quickly dove into the details of sentence construction. Melissa Arbus Sherry, arguing for Boechler, contended that the statutes vague parenthetical reference to jurisdiction could not close those courthouse doors. Assistant to the Solicitor General Jonathan Bond, arguing for the government, contended that when the language granted jurisdiction over such matter, it clearly referred to a petition that meets both of the first clauses requirements, including submission of the petition within 30 days. Yet no comment from the bench fully embraced the governments argument that the statutory language incontrovertibly made the statute of limitations jurisdictional. At one point, Justice Neil Gorsuch described three possible interpretations, two of which favored the government.

Sherry faced her strongest challenge from Chief Justice John Roberts, who emphasized that the statute includes the statement that a court shall have jurisdiction. Why should it matter, Roberts asked, whether that statement is in a parenthetical?

Sherrys statutory construction argument drew a friendly amendment from Justice Sonia Sotomayor, who suggested that the noun determination was the antecedent for such matter, rather than the verb petition which the briefing had emphasized. (Im actually trying to help you, Sotomayor explained to Sherry. Im the one shes trying to hurt, interjected Roberts.)

Justice Samuel Alito seemed to agree with Sherry that the placement of the jurisdictional language in the parenthetical was important. He suggested that this might make it an aside, as if Congress were saying, by the way, the Tax Court has jurisdiction. Justice Elena Kagan asked directly: What would it take to make the statute jurisdictional? Conditional language, such as the use of if, is the best way, replied Sherry. But is it the only way?

In the course of the governments argument, Justice Amy Coney Barrett pressed on the meaning of a clear statement rule, by asking what should happen if the governments interpretation is maybe a little bit more plausible but not a slam dunk? Bond responded that a statute should be treated as a clear statement barring equitable tolling if the court decided that was the most reasonable reading at least, as long as the statutory section had the word jurisdiction in it. But the approach of suggesting that a statute containing the word jurisdiction is clearly jurisdictional unless it is ambiguous did not seem persuasive for most justices. Justices Brett Kavanaugh and Stephen Breyer even suggested that the Treasury Department and the solicitor generals office might help inform Congress of the content of the courts clear-statement jurisprudence, in order to encourage better drafting.

Justice Clarence Thomas raised the point that a subsequent statutory subsection, 26 U.S.C. 6330(e)(1), says that the Tax Court has jurisdiction to enjoin an action only if an appeal is timely. Why, Thomas asked, would Congress permit the Tax Court to consider an untimely action but then not allow it to enjoin a levy? Bond argued that timely meant that the petition had been submitted within the 30-day period, while Sherry argued that timely incorporates the possibility of tolling. Breyer took Sherrys side with the help of a law dictionary definition. If a court extended the legal deadline, said Breyer, therefore, it is timely.

The argument also tested the idea that a decision in favor of Boechler could have a narrow scope. When Thomas asked for numbers, Bond replied that the new precedent would have relevance for about 26,000 collection due process cases per year. Of those 26,000 cases, 1,200 produce taxpayer petitions for Tax Court review and 300 are dismissed for lack of jurisdiction. When Kavanaugh asked whether equitable tolling should be pretty tightly cabined, Sherry responded that the courts recent precedent on the standard for equitable tolling would apply in exactly the same way here.

Kavanaugh also asked about the impact of a Boechler decision on other tax statutes of limitations, in particular Section 6213(a), which provides the gateway to, Bond said, 95% of the Tax Courts docket and gives a taxpayer 90 days to petition for Tax Court review of a notice of deficiency. Bond said that a Boechler decision would not disturb the precedent holding that Section 6213(a)s deadline cannot be equitably tolled.

Sherry also developed the argument that the collection due process procedure is equitable at every turn. She argued that CDP focuses on the equities of a particular taxpayers situation because it focuses on collection alternatives, which might, for instance, allow a taxpayer to establish a repayment schedule rather than permitting the IRS to seize and sell property to pay tax debts. Bonds counterargument that Congress specified only tolling exceptions that the IRS can more easily administer, for instance for bankruptcy and combat-zone military service seemed to fall flat.

The Boechler argument suggests that most of the justices lean toward allowing the consideration of equitable tolling in the specific context of tax CDP proceedings. A majority may find dispositive the principle of insisting upon and encouraging clearer statutory language from Congress. Some justices may also consider the equitable nature of collection due process proceedings an important point in the firms favor. When the court puts these two considerations together, a narrow decision in favor of Boechler will likely result.

Posted in Merits Cases

Cases: Boechler, P.C. v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue