A VEW FROM THE COURTROOM

“Feelings run high”: Two hours of tense debate on an issue that divides the court and the country

on Dec 1, 2021 at 7:22 pm

A View from the Courtroom is an inside look at significant oral arguments and opinion announcements unfolding in real time.

Outside the Supreme Court building, crowds of demonstrators have gathered for today’s major argument in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. Inside the building, though, the new normal that has existed since the justices returned to the bench in October prevails.

Of course, the courtroom would be packed if we weren’t still under pandemic restrictions. Advocates on each side would have pulled strings for tickets, some members of Congress would have likely showed up, and regular people would have spent days and nights in line outside for the chance to watch the argument.

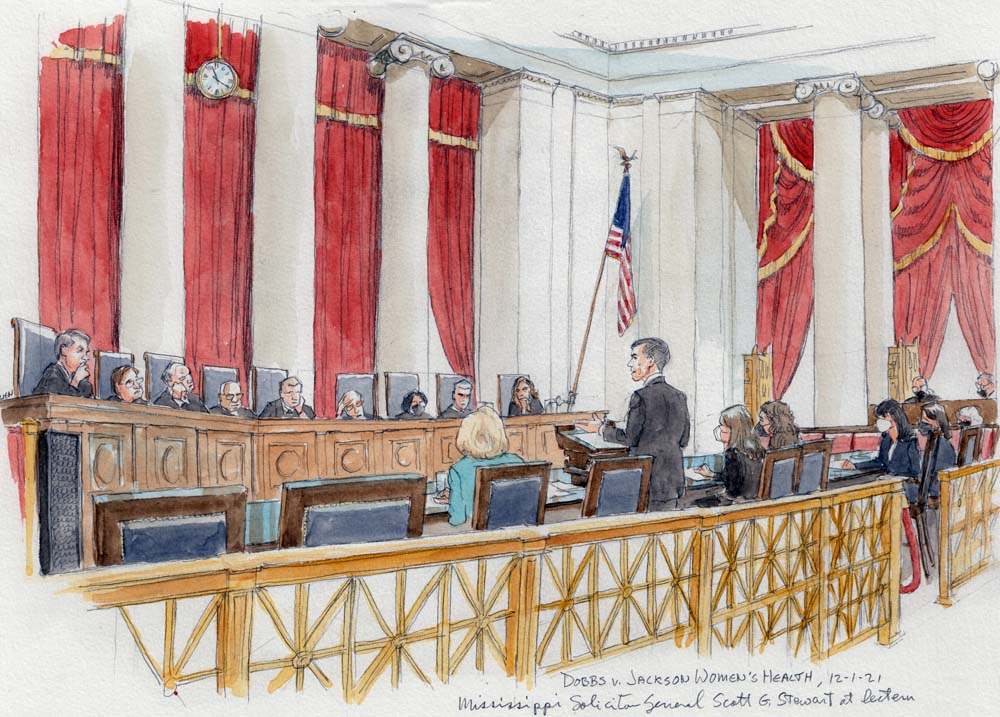

But today, the only attendees will be the three arguing lawyers (and their second chairs), essential court personnel, most if not all of the justices’ law clerks, two spouses of justices, three sketch artists, and 18 news correspondents. And in due time, the justices themselves.

U.S. Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar, accompanied by one of her assistants, Erica Ross, is the first to enter the bar section, around 9:45 a.m. A few minutes later, Julie Rikelman of the Center for Reproductive Rights, who will argue for Jackson Women’s Health, arrives along with her second chair, Hillary Schneller, also of the center.

And just six minutes before 10, Mississippi Attorney General Lynn Fitch arrives with state Solicitor General Scott Stewart, who will argue in defense of the state’s prohibition on abortion after 15 weeks of pregnancy.

All three legal teams have cut it a little close, and in a departure from normal custom, they do not greet each other or shake hands.

More law clerks file in as the argument nears, filling almost every designated space, as the court is still requiring some degree of social distancing. If law professor Josh Blackman’s recent “thought experiment” to phase out law clerks to the justices takes hold, this clerk class would be among the last. Two of the three lawyers arguing today clerked on the high court (Prelogar for Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Elena Kagan, and Stewart for Justice Clarence Thomas). The current clerks have surely envisioned themselves arguing a major case in the future, if not also sitting on the bench one day.

Joanna Breyer arrives minutes before the argument and takes her seat in the guest box, where she will be joined about 15 minutes into the argument by Jane Roberts. Those two were present, and the only spouses present, for the Nov. 1 arguments in the previous abortion-related clash: Whole Woman’s Health v. Jackson and United States v. Texas.

Even before the justices take the bench, Stewart is chomping at the bit. He places his binder on the lectern and appears to test the height of the wooden stand. (The handcrank that adjusts the height got a bit of a workout on Monday when one lawyer lowered it several cranks and the next one cranked it back up.)

When the justices enter the courtroom, Stewart stays standing at the lectern rather than return to his seat, and he waits for Chief Justice John Roberts to call the case and recognize him. Perhaps he understands that there have been few if any preliminaries under the court’s COVID-19 protocols, such as bar admissions or opinion announcements from the bench.

Stewart makes clear — consistent with the aggressive stance the state has taken in its merits brief — that Mississippi is arguing for more than just upholding its 15-week ban.

“Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey haunt our country,” he says, referring to the landmark 1973 and 1992 abortion rulings he is asking the court to overrule. “They have no basis in the Constitution. They have no home in our history or traditions. They’ve damaged the democratic process. They’ve poisoned the law. They’ve choked off compromise. For 50 years, they’ve kept this court at the center of a political battle that it can never resolve. And 50 years on, they stand alone. Nowhere else does this court recognize a right to end a human life.”

Thomas asks the first question, as is now the norm, but it is soon Justices Stephen Breyer and Sonia Sotomayor who take the reins.

Breyer hits on a theme he enunciated as far back as Stenberg v. Carhart, a 2000 abortion case, as well as more recently during abortion arguments, about the country being deeply divided over the issue.

“Feelings run high,” Breyer says. “And it is particularly important to show what we do in overturning a case is grounded in principle and not social pressure, not political pressure.”

He emphasizes the Casey court’s discussion of stare decisis, reading from the opinion and even giving the page numbers in the United States Reports.

“And the last sentence, … they say overruling unnecessarily and under pressure would lead to condemnation, the court’s loss of confidence in the judiciary, the ability of the court to exercise the judicial power and to function as the Supreme Court of a nation dedicated to the rule of law.”

Stewart reaches to the counsel table and grabs what appears to be a printed copy of Casey, and he spends a moment trying to find the page Breyer is reading from before giving up. But he has an answer.

“I would not say it was the people that called this court to end the controversy. … Many people vocally really just wanted to have the matter returned to them so that they could decide it locally, deal with it the way they thought best and at least have a fighting chance to have their view prevail, which was not given to them under Roe and then, as a result, under Casey.”

Sotomayor is also prepared to put the case in stark perspective.

“Now the sponsors of this bill, the House bill, in Mississippi, said we’re doing it because we have new justices,” she says, adding that the same was true about a separate Mississippi law, passed earlier this year and not before the high court, that would ban abortion after six weeks of pregnancy.

“Will this institution survive the stench that this creates in the public perception — that the Constitution and its reading are just political acts?” Sotomayor says.

I’ll confess that I thought I heard her say “political hacks,” as if she were playing on the phrase Justice Amy Coney Barrett used during a speech this summer, when she insisted the justices are not “a bunch of partisan hacks.” But a close listen to the recording seems to confirm what is in the transcript: “political acts.” There was no mistaking, though, that Sotomayor said “stench,” a strong word not often heard in this courtroom.

Stewart has an answer for her.

“Justice Sotomayor, I think the concern about appearing political makes it absolutely imperative that the court reach a decision well grounded in the Constitution, in text, structure, history, and tradition, and that carefully goes through the stare decisis factors that we’ve laid out,” he says.

“Casey did that,” she replies.

“No, it didn’t, Your Honor, respectfully,” he says.

The chief justice, as he has done before, decides to interrupt Sotomayor after she has gone on at some length. (She will come back a few minutes later with, “May I finish my inquiry?”)

Roberts asks Stewart how fetal viability was addressed in Roe, noting that Justice Harry Blackmun, the author of that decision, revealed with the release of his personal papers that the viability line was “dicta.”

Roberts calls the papers, released five years after Blackmun’s 1999 death, “an unfortunate source.” Later in the argument, Roberts says the release of the Blackmun files “is a good reason not to have papers out that early.” So I think we will be waiting for the Roberts papers for a good long time.

Rikelman, who argued and won June Medical Services v. Russo in 2020, which struck down Louisiana’s abortion restrictions, takes to the lectern and tells the court, “Mississippi’s ban on abortion two months before viability is flatly unconstitutional under decades of precedent.”

After a few questions from Thomas, the chief justice zeroes in on Mississippi’s 15-week ban. Fifteen weeks is well before the point of fetal viability, which occurs around 24 weeks of pregnancy.

“If you think that the issue is one of choice — that women should have a choice to terminate their pregnancy — that supposes that there is a point at which they’ve had the fair choice … and why would 15 weeks be an inappropriate line?” Roberts asks. “Because viability, it seems to me, doesn’t have anything to do with choice. But, if it really is an issue about choice, why is 15 weeks not enough time?”

Rikelman says that, among other reasons, “without viability, there will be no stopping point. States will rush to ban abortion at virtually any point in pregnancy.”

Justice Samuel Alito presses Rikelman on a more philosophical question.

“What is the philosophical argument, the secular philosophical argument, for saying [viability] is the appropriate line?” he says. “There are those who say that the rights of personhood should be considered to have taken hold at a point when the fetus acquires certain independent characteristics. But viability is dependent on medical technology and medical practice. It has changed. It may continue to change.”

“No, Your Honor, it is principled,” she says, “because, in ordering the interests at stake, the court had to set a line between conception and birth, and it logically looked at the fetus’ ability to survive separately as a legal line because it’s objectively verifiable and doesn’t require the court to resolve the philosophical issues at stake.”

Prelogar, arguing for the United States in support of Jackson Women’s Health, says, “The real-world effects of overruling Roe and Casey would be severe and swift. Nearly half of the states already have or are expected to enact bans on abortion at all stages of pregnancy, many without exceptions for rape or incest. … If this court renounces the liberty interests recognized in Roe and reaffirmed in Casey, it would be an unprecedented contraction of individual rights and a stark departure from principles of stare decisis.”

Prelogar gets questions from all three of the “new justices.”

Justice Neil Gorsuch, who was silent during the June Medical argument in 2020 but voted in dissent to uphold the state’s restrictions, asks her, “If this court will reject the viability line, do you see any other intelligible principle that the court could choose?”

Justice Brett Kavanaugh asks, as he did of Rikelman, about what he characterizes as “the other side’s theme,” but which seems to reflect his thinking as well.

“When you have those two interests at stake [women’s bodily integrity and fetal life] and both are important, … why should this court be the arbiter rather than Congress, the state legislatures, state supreme courts, the people being able to resolve this?”

The newest of the new justices, Barrett, asks several times about so-called safe haven laws and adoption as alternatives to abortion.

“It seems to me,” she says to Rikelman, “both Roe and Casey emphasize the burdens of parenting, and insofar as you and many of your amici focus on the ways in which forced parenting, forced motherhood, would hinder women’s access to the workplace and to equal opportunities, it’s also focused on the consequences of parenting and the obligations of motherhood that flow from pregnancy.”

“Why don’t the safe haven laws take care of that problem?” Barrett continues. “It seems to me that it focuses the burden much more narrowly. There is, without question, an infringement on bodily autonomy, you know, which we have in other contexts, like vaccines. However, it doesn’t seem to me to follow that pregnancy and then parenthood are all part of the same burden.”

After nearly two hours of somber, serious, and compelling arguments, the chief justice declares that the case is submitted. After the justices leave the bench, Fitch walks over to shake hands with Prelogar, and the other lawyers follow her lead, with polite but perfunctory handshakes all around. The country and these parties remain sharply divided, but in the end custom and decorum prevail in the courtroom.