Justices suggest that Congress has leeway to exclude Puerto Rico from federal disability benefits

The Supreme Court on Tuesday probed Congress’ authority to deny welfare benefits to Puerto Rico and other U.S. territories, with several justices voicing concerns that a broad ruling in favor of equal treatment would upend numerous federal policies that differentiate between territories and states.

The case, United States v. Vaello-Madero, involves Supplemental Security Income, a federal program that provides cash assistance to low-income people who are blind, disabled, or at least 65 years old. Residents of all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the Northern Mariana Islands can qualify for the program, but residents of Puerto Rico and the other territories are excluded. The question for the court is whether that exclusion violates the principle of equal protection enshrined in the Fifth Amendment.

Despite President Joe Biden’s position that Puerto Rico residents should be eligible for SSI benefits, his administration defended the exclusion, saying it’s a policy choice that Congress is entitled to make. But several justices expressed skepticism that there is any rational justification for the policy.

“Puerto Ricans are citizens, and the Constitution applies to them,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor said. “Their needy people are being treated differently than the needy people in the 50 states.”

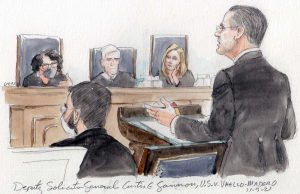

Deputy Solicitor General Curtis Gannon responded that Puerto Rico residents are exempt from paying many federal taxes, so Congress acted reasonably when it limited federal benefits for the island. But Sotomayor and Justice Stephen Breyer scoffed at that rationale, noting that virtually anyone with an income low enough to qualify for SSI would pay no federal income taxes anyway.

“There is no real connection between the SSI beneficiaries and federal taxes,” Breyer said.

Sotomayor, whose parents were born in Puerto Rico and is a self-described “Nuyorican,” pressed Gannon on the 120-year history of Puerto Rico’s unfavorable treatment by the U.S. government. That history, she said, includes the Insular Cases, a series of early-20th-century rulings in which the court used racist assumptions in denying full constitutional protections to territories acquired in the Spanish-American War. Discrimination against Puerto Rico’s 3.2 million residents, who lack voting representation at the federal level, persists to this day, Sotomayor said — and she suggested that the court should analyze the constitutionality of the SSI exclusion in light of that legacy.

Gannon responded that the SSI statute draws distinctions based on geography, not race or ethnicity. “There is no evidence here linking this exclusion to ethnicity or a history of discrimination,” he said.

Sotomayor shot back: “How do you separate it out? Puerto Ricans are Puerto Ricans. They’re Hispanic, and they are routinely denied a political voice. They’re powerless politically. All you have to do is listen to some of the rhetoric about Puerto Rico and you know there has been discrimination.”

Sotomayor was not the only one concerned about the Insular Cases, which have been heavily criticized but never formally overturned. Both Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Neil Gorsuch inquired about their relevance, with Gorsuch asking whether the court should state explicitly “what everyone knows to be true” — that they were wrongly decided. Gannon replied that “some of the reasoning and rhetoric” in the Insular Cases are “obviously anathema,” but they are not relevant to this case.

The court devoted more time to exploring the potential ramifications on modern-day legislation if the SSI exclusion is deemed unconstitutional. At least five justices — Roberts, Breyer, Samuel Alito, Elena Kagan, and Amy Coney Barrett — asked some form of the following question: Is Congress really required to treat all states and territories on equal terms, and if so, wouldn’t numerous federal benefits programs (not to mention other federal laws) be in jeopardy?

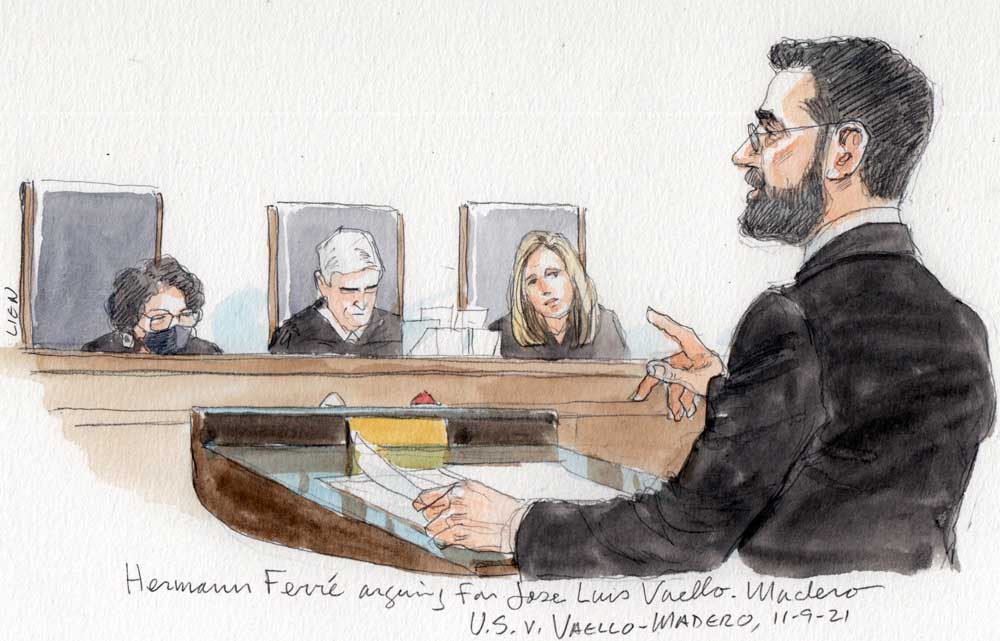

Hermann Ferre argued on behalf of Jose Luis Vaello-Madero, a disabled man who was sued by the federal government for $28,000 after he moved from New York to Puerto Rico and continued to collect SSI benefits. Ferre gave varying answers to the justices’ questions about how a victory for Vaello-Madero would affect other laws. At one point, he suggested that the Constitution requires all federal laws to treat individuals in states and territories equally. At a different point, he attempted to limit his argument to the SSI program, an “exclusively federal” program in which the need for equal treatment might be greatest. Congress may have more latitude to engage in disparate treatment in other programs that involve state partnerships or take account of local conditions, Ferre said.

By the end of Tuesday’s 75-minute argument, the prevailing view on the bench was skepticism that the Constitution requires, as Barrett put it, “equal treatment across the board” when it comes to policies that affect territories. Justice Brett Kavanaugh seemed to speak for multiple justices when he acknowledged that Ferre made “compelling policy arguments” but suggested that the solution should come from the legislative branch.

Kavanaugh then pointed out that even the Constitution itself does not always put states on equal footing with one another. The Electoral College and the requirement that all states get two senators, Kavanaugh said, favor less populous states. And the Constitution’s territories clause — which several justices invoked throughout the argument — authorizes Congress to regulate U.S. territories as it sees fit, even if those regulations “may seem anachronistic to some,” Kavanaugh said.

“Congress has the ability, the role, to make changes over time,” he concluded. “It does not give that authority to this court.”

Congress is already considering a proposal to expand SSI to Puerto Rico. Biden included the provision in his “Build Back Better” package of social spending that is under negotiation on Capitol Hill. Even if the legislation passes, however, it likely will not affect Vaello-Madero’s case unless lawmakers eliminate the exclusion retroactively.

Posted in Merits Cases

Cases: United States v. Vaello-Madero