Justices uphold a narrow version of patent assignor estoppel

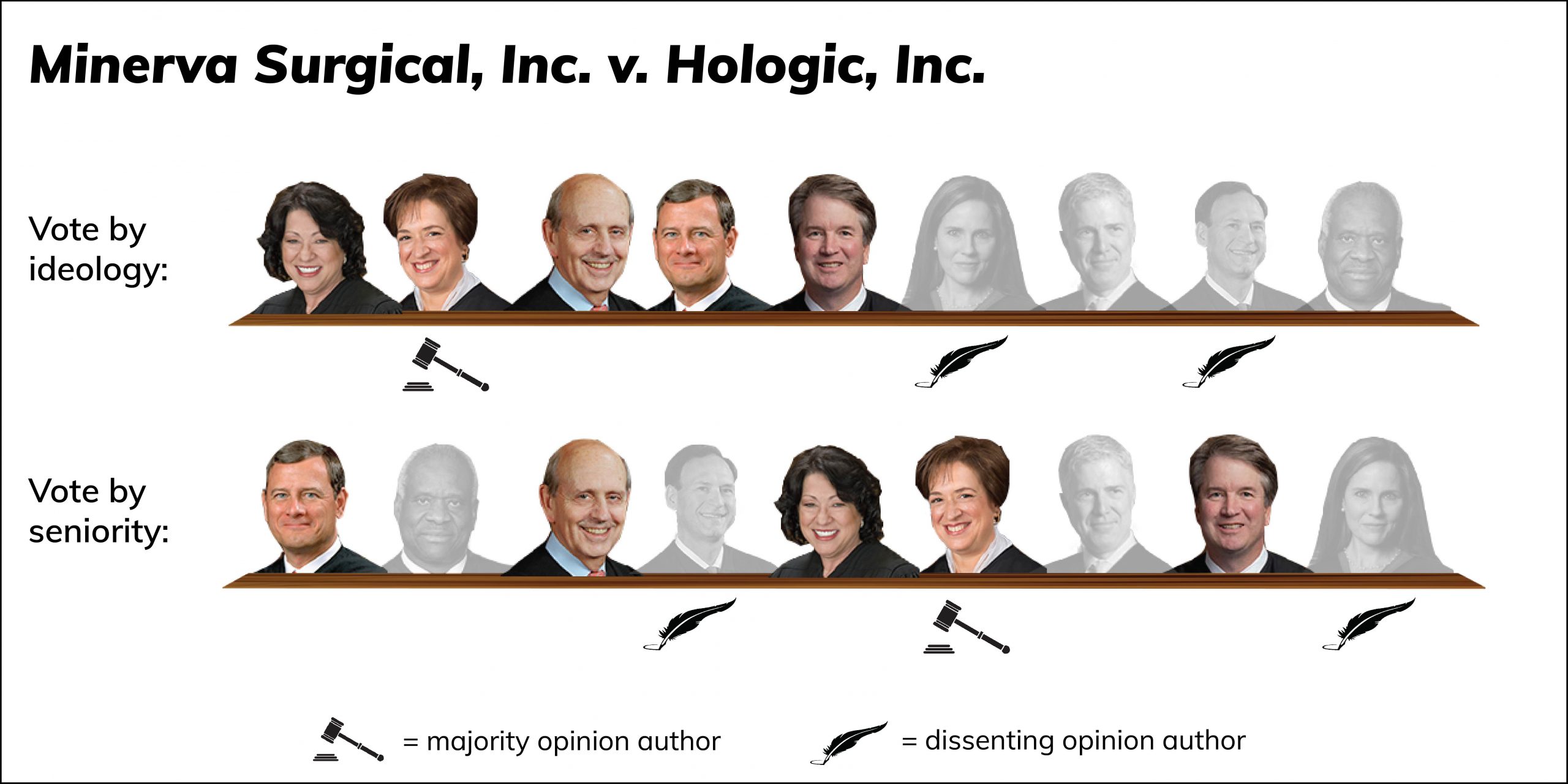

The Supreme Court on Tuesday narrowed the doctrine of patent assignor estoppel, which prohibits an inventor from assigning a patent to someone and then later contending in litigation that the patent is invalid. By a vote of 5-4, the court rejected calls to completely abandon the doctrine. But the court also rejected lower courts broad applications of the doctrine. The court instead clarified that assignor estoppel applies only when the assignors claim of invalidity contradicts explicit or implicit representations he made in assigning the patent.

The ruling in Minerva Surgical Inc. v. Hologic Inc. came in a dispute that arose when Hologic sued Minerva for patent infringement over a medical device used for endometrial ablation. Minerva tried to argue that Hologics patent was invalid.

The lower courts blocked Minerva from asserting invalidity because Minervas founder had filed the original patent applications and then sold the patent rights, which eventually ended up with Hologic. The lower courts ruled that the founders original assignment of patent rights prevented, or estopped, Minerva from contesting validity. Minerva asked the Supreme Court to abolish assignor estoppel.

Writing for the majority, Justice Elana Kagan emphasized that assignor estoppel is rooted in principles of fair dealing. It prevents the about-face when an inventor assigns a patent for value and then turns around and claims the patent is worthless. Kagan also relied on the doctrines long history, which dates back to 18th-century England, and which the Supreme Court has recognized for nearly a century.

Although the Patent Act does not provide for assignor estoppel, the court rejected claims that the Patent Act prohibits it. Although the act broadly allows parties to assert an invalidity defense, Kagan pointed out that many other recognized preclusion doctrines likewise prevent some invalidity arguments without running afoul of the Patent Act.

But the courts endorsement of assignor estoppel comes with limits, Kagan wrote. Although an inventor may not expressly or impliedly warrant that a patent is valid and then later deny validity, not all invalidity arguments conflict with the express or implied representations made at assignment. On this front, the court largely embraced the middle ground the government advanced in a friend-of-the-court brief. The governments brief urged the court to preserve assignor estoppel but limit it to its equitable core. Elaborating on this concept, Kagan wrote that the doctrine reaches only so far as the equitable principle long understood to lie at its core.

The court identified three examples of non-contradiction in which assignor estoppel should not apply. First, the majority addressed the common employment arrangement where an employee assigns an employer the patent rights in any future inventions he develops during his employment arrangement. Kagan wrote that the employees assignment contains no representation that a patent is valid, so the employee remains free to challenge the validity of any resulting patent. In one paragraph, Kagan knocked out of the principal criticisms of the doctrine. In carving out this limitation, Kagan cited Mark Lemleys influential article, “Rethinking Assignor Estoppel.”

The courts second example concerned a change in the law. If a previously valid patent becomes invalid due to a change in the law, no principle of consistency prevents the assignor from saying so.

Kagan then addressed the scenario likely to affect the outcome in this case. Here, the inventor (Minervas founder) assigned the patent rights arising from an application that had not yet matured into an issued patent. The assignee changed the scope of the application after assignment. The court ruled that if the issued patent is materially broader than the assigned rights, then there is no inconsistency and thus no estoppel.

The parties to this case disagreed about whether the issued patent is in fact materially broader. To resolve this dispute, the court sent the case back to the lower courts, which had not ruled on the issue.

In reaching this holding, the majority expressly did not rely on stare decisis and therefore did not expressly decide whether to overrule Westinghouse Electric Manufacturing Co. v. Formica Insulation Co., the 1924 decision in which the Supreme Court first implicitly approved of assignor estoppel.

Justice Samuel Alito dissented, criticizing the majority for adopting a text-blind method of statutory interpretation with which I cannot possibly agree. Alito wrote that [n]ot one word in the patent statutes supports assignor estoppel, and went on to criticize the majority for avoiding squarely confronting the continuing validity of Westinghouse.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett, joined by Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch, also dissented. Like Alito, Barrett began with the premise that assignor estoppel conflicts with the text of the Patent Act. Barrett rejected the argument that Congress ratified Westinghouse in a 1952 statutory reenactment, and also rejected the argument that Congress legislated against a common-law backdrop that included assignor estoppel.

Posted in Merits Cases

Cases: Minerva Surgical Inc. v. Hologic Inc.