Opinion analysis

Court makes it easier for appellate courts to affirm federal felon-in-possession convictions after Rehaif

on Jun 15, 2021 at 2:08 pm

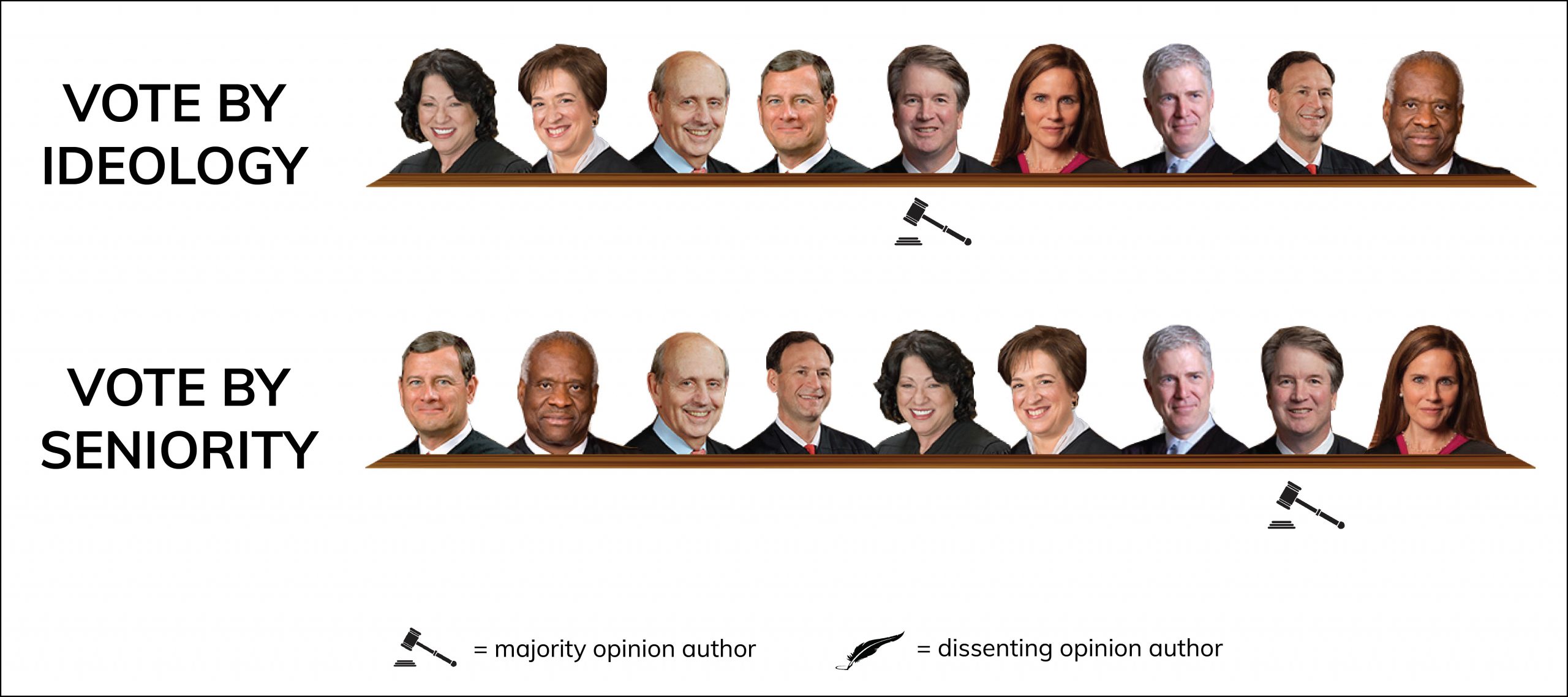

Federal felon-in-possession defendants who fail in the trial court to assert their rights under the Supreme Court’s 2019 decision in Rehaif v. United States face an “uphill climb” to get a new trial or plea proceeding, the court stated Monday in Greer v. United States and United States v. Gary. Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote for a unanimous court affirming Greer and an 8-1 majority reversing Gary, stating that “if a defendant was in fact a felon, it will be difficult for him to carry the burden on plain-error review of showing a ‘reasonable probability’ that, but for the Rehaif error, the outcome of the district court proceedings would have been different.”

Rehaif broke new ground by holding for the first time that, under 18 U.S.C. § 922(g), the federal statute barring people with prior felony convictions from possessing firearms, the government must prove that the defendant knew he was a felon at the time he possessed a firearm. Greer and Gary involved the standard for appellate courts to order new trials or plea hearings for people convicted under Section 922(g) who initially failed to invoke Rehaif. That group of people includes defendants who were convicted before Rehaif was decided but still had appeals pending at the time of the decision.

Kavanaugh’s opinion makes clear that, when a defendant has failed to assert Rehaif at his trial or plea hearing, the burden is on him to show the appellate court that there is a “substantial possibility” that he could produce enough evidence on remand that he did not in fact know of his felon status, such that he would not be convicted again. “The bottom line of these two cases is straightforward. In felon-in-possession cases, a Rehaif error is not a basis for plain-error relief unless the defendant first makes a sufficient argument or representation on appeal that he would have presented evidence at trial that he did not in fact know he was a felon,” Kavanaugh summed up.

“Common sense,” he continued, suggests that most people with felony convictions are aware of their legal status as convicted felons. “In a felon-in-possession case where the defendant was in fact a felon when he possessed firearms, the defendant faces an uphill climb in trying to satisfy the substantial-rights prong of the plain-error test based on an argument that he did not know he was a felon. The reason is simple: If a person is a felon, he ordinarily knows he is a felon. ‘Felony status is simply not the kind of thing that one forgets.’”

Kavanaugh recognized there could be exceptional cases. “Of course, there may be cases in which a defendant who is a felon can make an adequate showing on appeal that he would have presented evidence in the district court that he did not in fact know he was a felon when he possessed firearms,” he wrote. However, when the defendant has forfeited the Rehaif claim in the district court, he has the burden of showing some evidence on appeal demonstrating the lack of such knowledge. That’s true even for defendants who “forfeited” a Rehaif claim only because they were convicted before Rehaif was even decided. “If a defendant does not make such an argument or representation on appeal, the appellate court will have no reason to believe that the defendant would have presented such evidence to a jury, and thus no basis to conclude that there is a ‘reasonable probability’ that the outcome would have been different absent the Rehaif error.”

Neither Gregory Greer nor Michael Andrew Gary carried that burden, according to the court. Greer stipulated at trial that he had been convicted of a felony, in order to avoid the government conspicuously putting that fact before the jury, Kavanaugh pointed out. During his plea hearing, Gary admitted to the court that he had been convicted of a felony.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor agreed with the court that Greer had failed to carry his burden, but she declined to draw the same conclusion as to Gary. “Unlike this Court, I would not decide in the first instance whether Gary can make a case-specific showing that the error affected his substantial rights,” she wrote.

Sotomayor also stressed that the majority’s language about defendants bearing a heavy burden to show that they did not know about their felon status applies only to plain-error analysis, when the defendant has failed to raise his Rehaif rights in the trial court. If the defendant does raise Rehaif below, then harmless-error analysis applies on appeal, and the burden is on the government to prove that the trial court’s failure to apply Rehaif was harmless beyond a reasonable doubt, Sotomayor stated.

The court’s holding that defendants must demonstrate a reasonable probability of a different result had they asserted their Rehaif rights below doomed the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit’s “structural error” approach in Gary. When a trial court’s error is treated as structural — as with ineffective assistance of counsel, for example — the appellate court must automatically vacate the conviction and remand to the trial court because the error is thought to have so thoroughly infected the proceedings below that an appellate court could not begin to put the pieces back together, so to speak. But Kavanaugh made short work of that approach, saying, “As the Court’s precedents make clear, the omission of a single element from jury instructions is not structural.” Even Sotomayor rejected the structural-error approach.

Much in the briefs and oral argument was devoted to the question of where an appeals court may look to find evidence showing that the defendant knew all along he was a felon within the meaning of Section 922(g), thus avoiding the need for a remand. In Greer, the appeals court looked outside the trial record to the full district court record to find evidence of such knowledge in the pre-sentence report. Kavanaugh’s opinion explicitly validates that practice, but at the same time appears to render it superfluous by saying that Greer’s stipulation under the 1997 Supreme Court decision in Old Chief v. United States that he had previously been convicted of a felony constituted competent evidence of such knowledge. (Defendants commonly enter into Old Chief stipulations in Section 922(g) cases so that the government need not enter prior convictions into evidence, potentially prejudicing the jury.) In Gary, the court’s opinion also would appear to moot any question of whether the appeals court could look to a pre-sentence report when it found evidence of knowledge of felon status in Gary’s plea colloquy admission that he had previously been convicted of a felony — an admission that happens in every Section 922(g) guilty plea hearing.

Following Greer and Gary, the issue is likely to be what sort of evidence will be sufficient to demonstrate a “reasonable probability” that, but for the Rehaif error, the outcome of the district court proceedings would have been different. In other words, what are the paradigm cases where a defendant has shown a sufficient possibility that he did not know of his felon status at the time he possessed the firearm, such that he becomes entitled to a new trial or plea hearing? Sotomayor offered a couple of possible fact patterns.

“Most obviously, as the Court recognized in Rehaif, a person who was convicted of a prior crime but sentenced only to probation may not know that the crime was ‘punishable by imprisonment for a term exceeding one year,’” she wrote. “Even if a defendant was incarcerated for over a year, moreover, that does not necessarily eliminate reasonable doubt that he knew of his felon status. For example, a defendant may not understand that a conviction in juvenile court or a misdemeanor under state law can be a felony for purposes of federal law. Or he likewise might not understand that pretrial detention was included in his ultimate sentence.”