OPINION ANALYSIS

Bond eligibility for certain noncitizens divides court along ideological lines

on Jun 29, 2021 at 3:57 pm

Congress provided that noncitizens who have been removed from the country but are found back in the United States should be expeditiously removed again. The second deportation occurs through a reinstatement of the first removal order, normally without further hearing, procedure or review. A narrow exception allows people in that situation to apply for “withholding” relief, which does not render the noncitizen any less deportable or otherwise give them the right to remain in the U.S. However, it prevents their deportation to a particular country where they might be tortured or persecuted. In an opinion on Tuesday in Johnson v. Guzman Chavez, the court ruled against a group of noncitizens who applied for withholding relief and sought hearings to determine if they could be released on bond while immigration authorities reviewed their withholding claims.

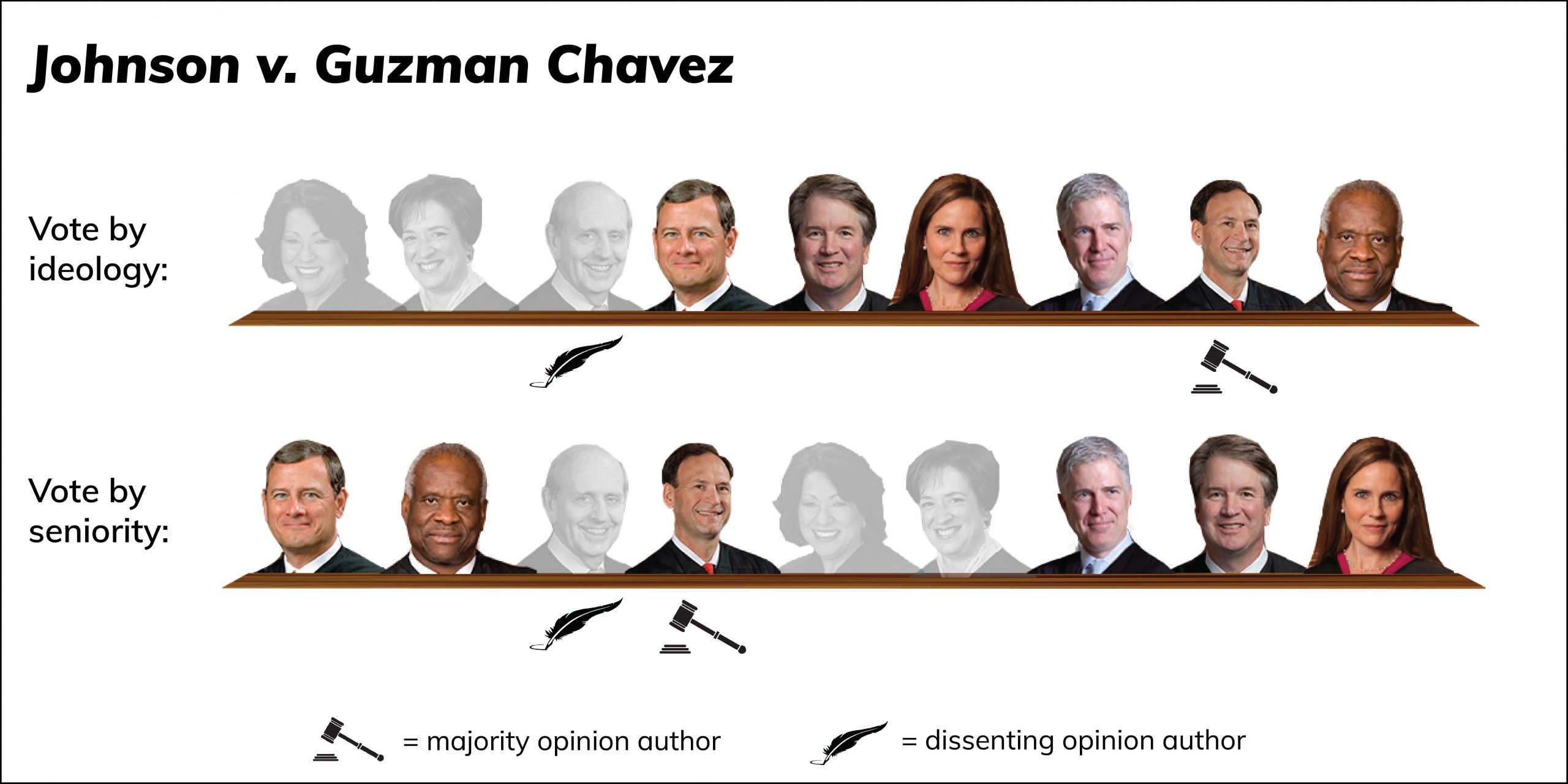

The court divided along conservative and liberal lines. Justice Samuel Alito wrote the opinion for a six-member majority. Justice Stephen Breyer dissented for himself and Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan.

Concretely, the question was whether, as the noncitizens argued, the more lenient and neutral bond process of 8 U.S.C. § 1226 governed; it applies “pending a decision on whether the alien is to be removed,” and it allows a noncitizen the opportunity for a bond hearing before an immigration judge. The government contended that 8 U.S.C. § 1231 controlled. That section generally applies “when an alien is ordered removed” and the order is “administratively final.” Under that section, a noncitizen is to be removed within 90 days, and if removal is not carried out within that period, bond is granted or denied by immigration administrators. In practice, noncitizens are much less likely to be released under Section 1231. Given the division in the circuit courts on the issue, it is fair to say that the question of which section applied in this special circumstance was difficult.

Alito first reasoned that noncitizens subject to reinstated removal orders had been “ordered removed” and those orders were “administratively final.” Accordingly, the literal language of Section 1231 applied. That the noncitizens could apply for withholding relief did not alter the conclusion that the removal orders existed and were administratively final. The key was the limited nature of withholding relief: “It relates to where an alien may be removed,” Alito wrote. “It says nothing, however, about the antecedent question whether an alien is to be removed from the United States.” Alito gave no weight to a consideration credited by the dissent and lower courts — namely that, as a practical matter, most people who are granted withholding relief remain in the U.S. indefinitely: “[T]he fact that alternate-country removal is rare does not make it statutorily unauthorized.” To Alito and the rest of the majority, a reinstated removal order means that the noncitizen’s removability has been conclusively established — even though the withholding claim means that the person might, in practice, never be removed from the United States.

The majority also rejected a paradox advanced by the noncitizens and embraced by the dissent: Section 1231 contemplates removal within 90 days of administrative finality of a removal order. In the case of a reinstated removal order, the 90 days would normally have expired shortly after the initial order and the initial removal. This date would often be long before the noncitizen returned to the United States or was apprehended. Section 1231 could not apply, the noncitizens and dissenters argued, because Congress could not have contemplated that a person would be removed within 90 days of a date years in the past. But Alito found no inconsistency, concluding that the section contained exceptions when removal was impossible in the specified period.

Alito also considered the arrangement of the statutory provisions, which “proceed largely in the sequential steps of the removal process.” “Section 1226 applies before an alien proceeds through removal proceedings and obtains a decision,” he noted, whereas Section 1231 “applies after.” He concluded that the court’s decision is consistent with the evident policy of Congress: “Aliens who have not been ordered removed are less likely to abscond because they have a chance of being found admissible, but aliens who have already been ordered removed are generally inadmissible” and thus are more likely to flee.

Breyer’s dissent began with a policy argument based on the practical reality that withholding proceedings are often protracted: “Why would Congress want to deny a bond hearing to individuals who reasonably fear persecution or torture, and who, as a result, face proceedings that may last for many months or years[?]” Breyer’s textual claim was that a removal order is not administratively final until the withholding claim is resolved by an immigration judge and the Board of Immigration Appeals because a withholding claim constitutes “seeking what is in effect a modification of, a change in, or a withholding of, the ‘prior order of removal.’” Under this reading, Section 1231 would not apply, and Section 1226 would. But again, the majority disagreed with the dissent’s conception of the nature of a withholding claim, concluding that it does not affect the validity or finality of the underlying reinstated removal order.

Justice Clarence Thomas filed a concurrence and was joined by Justice Neil Gorsuch. Thomas argued that, because this case did not involve review of a final order of removal, and was not based on another express jurisdictional grant, the Immigration and Nationality Act did not give federal courts jurisdiction, and the noncitizens’ claims should have been dismissed on that basis. The other four justices in the majority, and the three dissenters, disagreed.

There was also a terminological disagreement. Alito and Thomas both used the word “alien” to refer to a person who is not a national or citizen of the United States. That term is often used in the Immigration and Nationality Act. Breyer, in parts of his dissent, used “noncitizen,” the nomenclature preferred by those who contend that “alien” is dehumanizing. Justice Brett Kavanaugh is among the justices who prefer the term “noncitizen.” The solicitor general’s office also has recently used “noncitizen” in place of “alien.”