An immigration ruling with strict consequences for some non-citizens seeking deportation relief

Update (Tuesday, March 9, 1:35 p.m.): This article has been expanded with additional analysis.

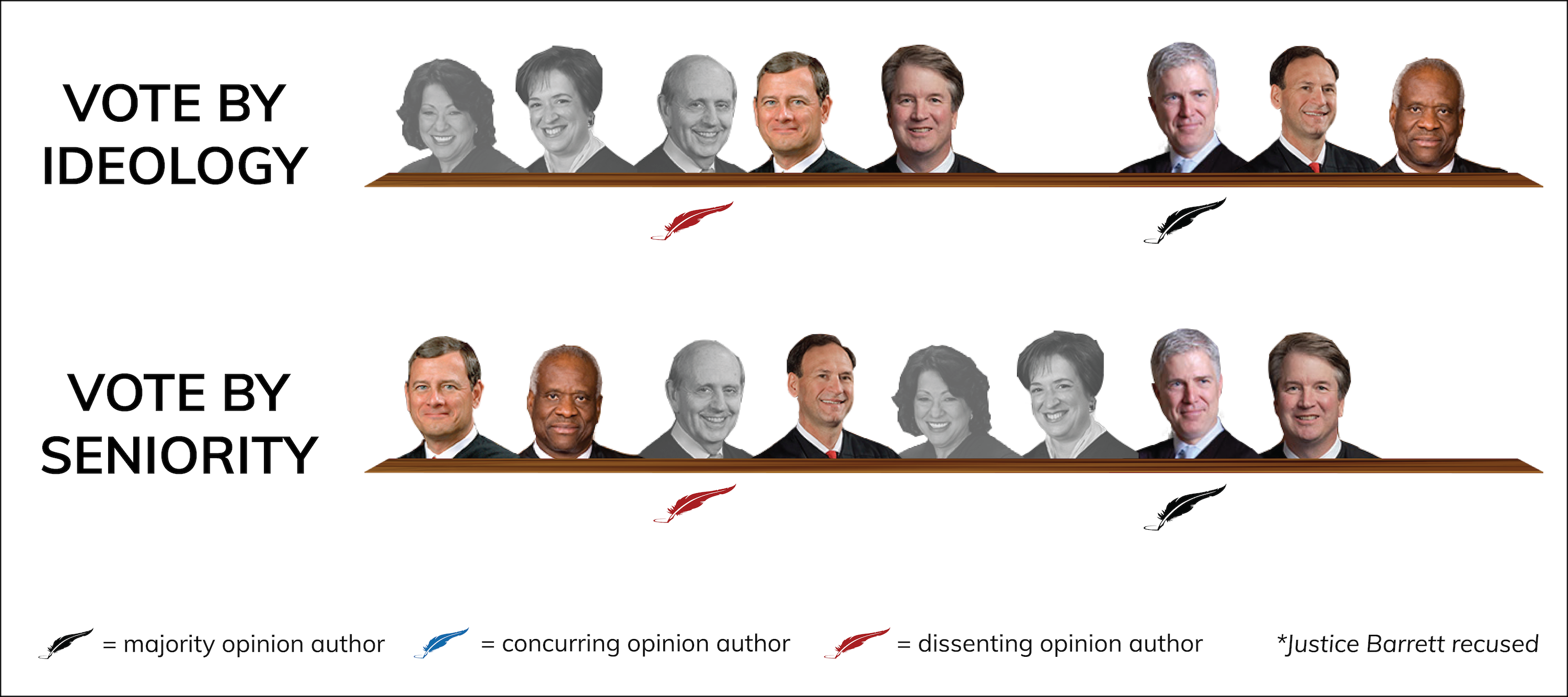

The Supreme Court on Thursday issued its opinion in Pereida v. Wilkinson, a case about whether an immigrant living in the country without authorization can seek relief from deportation for a minor crime. The court ruled 5-3 that because the noncitizen bears the burden to prove he is eligible for relief, he cannot carry that burden when his criminal record is unclear as to whether he was convicted of a crime that disqualifies him from relief. Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote the opinion for the court. Justice Stephen Breyer wrote a dissent in which Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan joined. Justice Amy Coney Barrett did not participate in the case because the oral argument occurred before she joined the court.

Clemente Pereida entered the United States without authorization nearly 25 years ago. He and his wife have three children, one of whom is a U.S. citizen and another of whom is a recipient of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, known as DACA. In order to obtain employment at a cleaning company, Pereida allegedly presented a false Social Security card. He was subsequently convicted of a misdemeanor for attempting to commit the Nebraska crime labeled “criminal impersonation.” Pereida was sentenced to a fine of $100 and no jail time.

Immigrants like Pereida — who have a long history in the United States and close relatives who are U.S. citizens or lawful permanent residents — are eligible to apply for a benefit that would cancel their deportation based on hardship to these relatives. This benefit, however, is not available to individuals without lawful immigration status who have been convicted of a “crime of moral turpitude” under Section 240A(b)(1)(C) of the Immigration and Nationality Act. Nebraska’s criminal-impersonation law includes several distinct offenses. Those versions that require intent to deceive are considered crimes involving moral turpitude under federal law and trigger immigration consequences. The other versions do not. Pereida’s criminal record, however, does not make clear which version of the offense he was convicted of.

The government argued that the statutory burden of proof placed on the immigrant seeking relief applies to the provision covering disqualifying crimes, and because Pereida could not prove that he was not convicted of a crime of moral turpitude, he was ineligible for relief. Consequently, under the government’s rule, an immigration judge could not consider the hardship that his deportation would have on his U.S. citizen child. Pereida argued that this rule breaks with the court’s precedent on how to determine whether state criminal convictions trigger immigration consequences under federal law.

The court ruled that the question of which offense contained within a divisible statute a prior conviction was for is a factual one. “And where, as here, the alien bears the burden of proof and was convicted under a divisible statute containing some crimes that qualify as crimes of moral turpitude, the alien must prove that his actual, historical offense of conviction isn’t among them,” Gorsuch wrote. Acknowledging record-keeping problems can arise that would make it difficult to bear this burden when court documents are incomplete or unavailable, Gorsuch concluded that “Congress was entitled to conclude that uncertainty about an alien’s prior conviction should not redound to his benefit,” and that notwithstanding hardships that may be faced by immigrants in other cases, “[i]t is hardly this Court’s place to pick and choose among competing policy arguments like these along the way to selecting whatever outcome seems to us most congenial, efficient, or fair.”

The court went on to suggest that the categorical approach used to determine whether immigration consequences attach when Congress has tied them to “convictions” in its statutes is not required. Here, the court stated that the Sixth Amendment concerns that limit judges to considering only certain court records for criminal purposes are not present in the immigration context. Thus, Pereida may have been able to introduce additional documents to prove that he was not convicted of a disqualifying crime.

Breyer’s dissent fears that the majority opinion, by creating a “‘threshold’ factual question” before the categorical approach applies, “will result in precisely the practical difficulties and potential unfairness that Congress intended to avoid” by allowing deportation to turn on the vagaries of criminal records noncitizens cannot control and the resources available to gather them. According to the dissent, there is no factual question and therefore the winner is not determined by the burden of proof. Because Congress chose to limit deportation relief for people with certain “convictions,” this case requires the application of the modified categorical approach in the same manner the court has directed in the past: “None [of the appropriate criminal records before the Immigration Judge] shows that Mr. Pereida’s convection necessarily involved facts equating to a crime involving moral turpitude. … The Immigration Judge thus cannot characterize the conviction as a conviction for a crime involving moral turpitude. That resolved this case.”

Under the majority’s reasoning, the decision is limited to cutting off deportation relief when a noncitizen’s conviction could be for a disqualifying or non-disqualifying offense and the criminal records are unclear. Despite suggesting that Congress could depart from the categorical approach, the court recognized that Congress has invoked this approach through its statutory language in much of the Immigration and Nationality Act. Further, the list of additional records the court invokes at the end of its opinion is still limited to official court documents. Whether the decision will summon a fundamental break with the categorical approach in immigration cases remains to be seen. What is clear is that unavailable or insufficient court records will prevent many long-time immigrants from even asking an immigration judge to consider the hardship of deportation on their U.S. citizen or lawful permanent resident family members. For them, instead of leaving the decision to the immigration judge’s discretion, deportation is now mandatory.

Posted in Merits Cases

Cases: Pereida v. Wilkinson