Case preview: Justices again take on anti-robocall law

on Dec 7, 2020 at 4:57 pm

On Tuesday, in Facebook v. Duguid, the Supreme Court for the second time this year will hear oral argument on the federal law that bans robocalls and robotext messages to cellphones. The question before the court this time is whether calls and texts sent using certain automated messaging systems are covered by the robocall ban — including predictive technology that calls or texts targeted customers, based, for example, on the vast data now collected on American consumers.

Why does this matter? Because since the Telephone Consumer Protection Act was enacted in 1991, telemarketing has changed dramatically. While targeted automated calls and texts — and, for that matter, cellphones — were starting to materialize in the early 1990s, they are now pervasive. Does the robocall law forbid them without a consumer’s consent, or does it only ban robocalls and robotexts made by older technology that dials random or sequential numbers? The answer to that statutory question is likely to have huge implications for the future of both marketing and cellphone spam.

Enacted in 1991, the TCPA responded to widespread consumer “outrage[] over the proliferation of intrusive, nuisance calls to their homes from telemarketers.” Congress pointed to evidence that consumers consider automated calls to be “a nuisance and an invasion of privacy.” The TCPA’s lead Senate sponsor went so far as to describe automated and prerecorded calls as “the scourge of modern civilization,” “hound[ing] us until we want to rip the telephone right out of the wall.”

The part of the statute at issue in Duguid bans “using any automatic telephone dialing system or an artificial or prerecorded voice” — both of which the Federal Communications Commission considers “robocalls” — to call or text cellphones, as well as emergency telephone lines, hospital patient rooms, pagers, and phones that charge for incoming calls, among others. The FCC, state attorneys general and private parties are authorized to sue those who don’t comply with the law; the penalty is up to $1,500 per call.

Noah Duguid sued Facebook, alleging that the company violated the TCPA by using an automatic telephone dialing system to send text messages to his cellphone without his consent. Duguid is not a Facebook user and had not given Facebook his number. Facebook mistakenly sent Duguid multiple text message as part of its policy of automatically sending a computer-generated text message to a user’s cellphone when their account is accessed from an unknown device. Duguid contacted Facebook to get the messages turned off, but he continued to receive them for several months.

Since the passage of the TCPA, the definition of automatic telephone dialing system, or ATDS, has remained the same: “equipment which has the capacity — (A) to store or produce telephone numbers to be called, using a random or sequential number generator; and (B) to dial such numbers.”

Duguid argued that Facebook’s text messages were sent by an ATDS without his consent and are therefore unlawful. The statute covers equipment that can “store” “numbers to be called” and “dial such numbers” without human intervention, regardless of whether the equipment uses a random or sequential number generator, he argued. Facebook, he said, used just such a system to send him text messages.

Facebook responded that “[f]ar from alleging en masse distribution to randomly or sequentially generated numbers” required by the definition of an ATDS, Duguid complained only that Facebook sent him personally targeted messages. The TCPA, the social network argued, only covers equipment that uses a random or sequential number generator — which Duguid acknowledges Facebook’s text messaging system does not.

Facebook also argued that the TCPA violates the First Amendment due to exceptions in the statute. The cellphone robocall ban originally included two exceptions: emergency calls and those made with the prior consent of the recipient. In 2015, Congress amended the TCPA to add a third exception for calls made to collect a debt owed to or guaranteed by the federal government. (That exception was at issue in the court’s first collision with the TCPA earlier this year in Barr v. American Association of Political Consultants). Facebook contended that the government-debt and emergency exceptions made the law “content-based” — a First Amendment catchphrase that refers to restrictions on the freedom of expression that apply differently depending on the topic of the expression. Specifically, Facebook argued that callers could make automated calls about some topics (government-backed loans, emergencies) but not about others (such as Facebook’s login notifications). Because the law was content-based, the company said, the most stringent form of First Amendment review — strict scrutiny — should apply, and under that standard the cellphone robocall ban should be struck down entirely.

A federal district court accepted Facebook’s statutory defense and declined to reach its First Amendment argument. The court dismissed Duguid’s complaint on the grounds that he failed to plausibly allege that the “text messages he received were sent using an ATDS.” That was because, the court concluded, “Facebook’s login notification text messages are targeted to specific phone numbers and are triggered by attempts to log in to Facebook accounts associated with those phone numbers,” not sent “en masse to randomly or sequentially generated numbers,” as prohibited by the statute.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit reversed. Following its own 2018 decision in Marks v. Crunch San Diego, LLC, the 9th Circuit concluded that, in the statutory definition of an ATDS, the adverbial phrase “using a random or sequential number generator” only modifies to “produce,” not “to store.” The court thus took the view that a device qualifies as an ATDS if it has the capacity “to store … numbers to be called” and “to dial such numbers automatically.” Then, reaching the constitutional question, the court found that the TCPA’s government-debt exception was content-based and violated the First Amendment, but it didn’t strike down the law. Instead it severed the exception from the rest of the act, leaving the general cellphone robocall ban in place — and so doing Facebook no good.

Facebook filed a cert petition asking the Supreme Court to hear both its statutory and constitutional challenges. The court held Duguid while it considered Consultants, which it decided in July. In Consultants, a group of political consultants that wanted to engage in political robocalls challenged the cellphone robocall ban on First Amendment grounds. The consultants argued, like Facebook, that the TCPA’s government-debt exception rendered the act content-based and unconstitutional. As the 9th Circuit had in Duguid, the Supreme Court found that the TCPA’s government-debt exception violated the First Amendment, but it declined to strike down the entire law. Instead, the court severed the government-debt exception from the rest of the act and left the general cellphone robocall ban in place; it thus gave the consultants a constitutional win but no relief.

Three days after the decision in Consultants, the Supreme Court granted Facebook’s petition limited to the company’s remaining statutory argument: whether the TCPA’s definition of “automatic telephone dialing system” encompasses a device that can store and automatically dial telephone numbers without using a random or sequential number generator.

As it did below, Facebook argues that the answer to that question is no. It maintains that usual grammar rules and various canons of statutory interpretation require the statutory phrase “using a random or sequential number generator” to apply to both verbs, “store” and “produce.” That definition of an ATDS makes sense of Congress’ purpose, Facebook contends: While Congress broadly banned unsolicited calls using a prerecorded or artificial voice, it imposed more limited restrictions on the use of an ATDS, which were of concern specifically because of their use of random or sequential number generators, which allowed them to simultaneously tie up all the lines in a hospital, police station, business or cellular network. What makes an ATDS automatic, Facebook argues, is the use of a random or sequential number generator. The practical consequences of adopting Duguid’s interpretation of the statute, Facebook contends, would also make every smartphone an ATDS subject to liability, raising First Amendment overbreadth concerns.

The federal government, which filed a brief in support of Facebook, likewise argues that a device is an ATDS only if it has the capacity to use a random or sequential number generator to store or produce telephone numbers. When a modifying phrase appears at the end of a list — as the adverbial phrase does here — the phrase typically modifies each item within the list, the government points out, rather than only the last item. The fact that “using a random or sequential number generator” is set off by a comma, it argues, further reinforces the conclusion that it applies both to “store” and “produce.” The federal government does not press Facebook’s First Amendment overbreadth argument.

Duguid counters that Facebook’s interpretation reads the first statutory verb, “to store,” out of the definition of an ADTS altogether. Because random and sequential number generators do not store numbers, but rather produce them, any equipment that makes use of such a generator will be captured by the verb “produce,” making “to store or” superfluous. Statutory interpretation, Duguid asserts, requires making sense of the words, namely the “commonsense linkage between produce and using a number generator.” Just like the phrase “He went forth and wept bitterly does not suggest that he went forth bitterly,” Duguid maintains, the statute does not suggest that the number-generator phrase modifies “store.” Facebook’s reading of the statute would also, Duguid asserts, “unleash the torrent of robocalls Congress wrote the TCPA to stop” because it would render the ban on robocalls “inapplicable to the vast bulk of automatically dialed calls and texts to cellphones.”

The case involves significant legal firepower: former Solicitor General Paul Clement represents Facebook, and Bryan Garner, a prominent textualist who published a book on interpretation with the late Justice Antonin Scalia, represents Duguid.

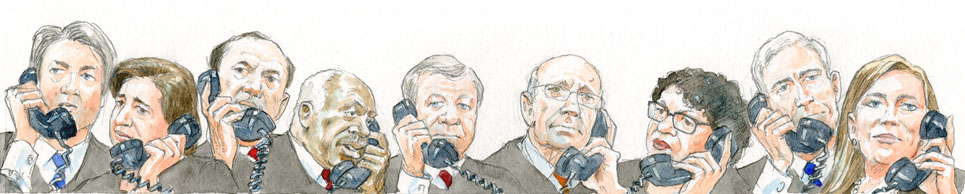

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the court will make live audio of Tuesday’s oral argument available to the public. The court is expected to issue its opinion by the end of June.