Empirical SCOTUS: How the court’s decisions have limited the national electorate

on Nov 18, 2020 at 3:05 pm

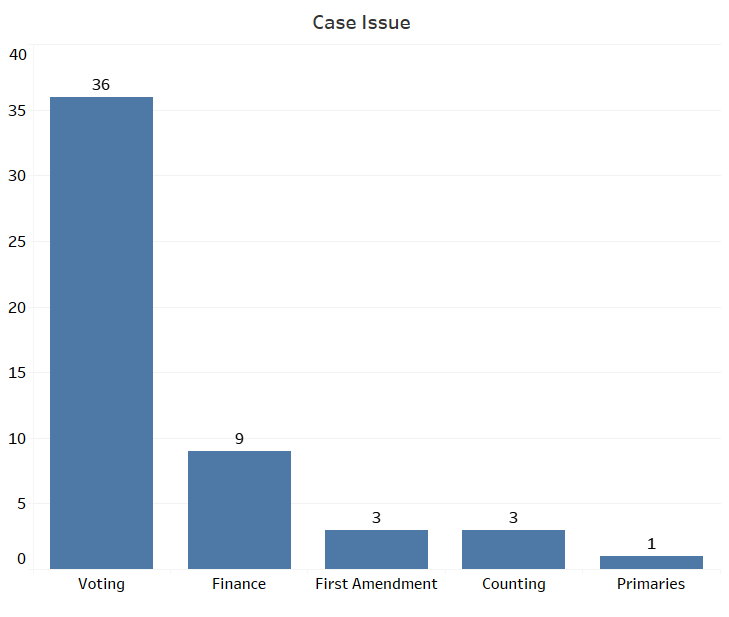

This article looks at the Supreme Court’s election law jurisprudence under the Roberts court. Supreme Court opinions and applications were searched from 2005 through the present for the term “election.” All cases were examined, and any that related to elections or voting procedures were maintained in the dataset. Cases were broken down across several issues including voting rights and procedures, vote counting, campaign finance and primaries. Several cases also dealt with First Amendment issues surrounding elections in the vein of Minnesota Voters Alliance v. Mansky, but these were not used because they dealt with peripheral issues rather than with voter participation. The breakdown of case types by frequency is as follows.

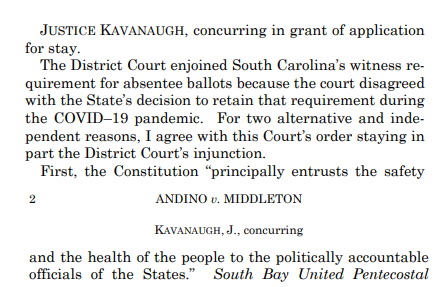

The justices’ votes were then coded in all cases as conservative or liberal. Conservative positions deferred to state election laws in voting cases, often limiting the voting population according to certain requirements. In campaign finance cases, conservative positions placed fewer limits on financial contributions. There are ample examples of the different positions even in the court’s decisions on emergency applications related to the 2020 election.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh articulated conservative deference to state law in his concurring opinion in Andino v. Middleton.

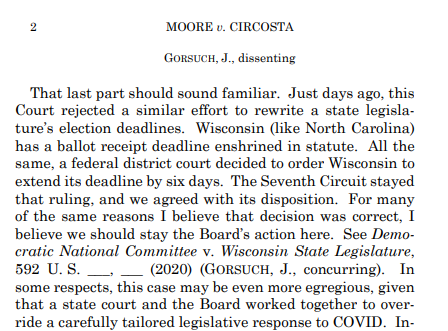

One risk of upholding state decisions, though, is that it can lead to inconsistent rules across jurisdictions. In dissent in Moore v. Circosta, Justice Neil Gorsuch highlighted different outcomes in emergency litigation involving ballot deadlines in Wisconsin and North Carolina. Gorsuch lamented that the court was not equally willing to sustain the constitutionality of state procedures in both instances.

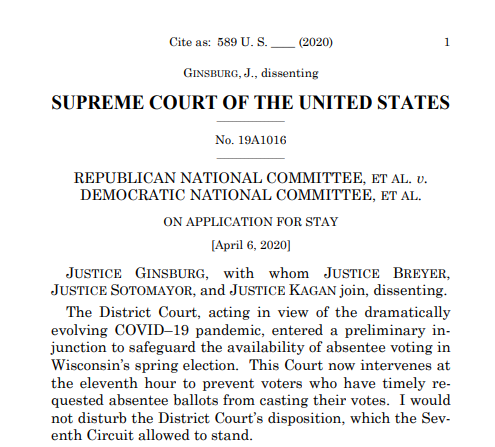

The court’s more liberal justices generally push for decisions looking to expand voter enfranchisement, as is articulated in Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s dissent in Republican National Committee v. Democratic National Committee.

Similar concerns were raised about voters’ health during the COVID-19 pandemic by Justice Sonia Sotomayor in her dissent in Merrill v. People First of Alabama.

Of course, these different views among the justices far predate the 2020 presidential election. Some might say the lines were clearly drawn in the court’s 5-4 decision in Shelby County v. Holder, the most consequential election law decision of the past decade. That decision struck down the formula in the Voting Rights Act that had been used to identify which jurisdictions, based on a history of voting-related discrimination, had to get advance permission from the federal government before changing their voting procedures. The majority opinion was written by Chief Justice John Roberts and joined by Justices Clarence Thomas, Antonin Scalia, Anthony Kennedy and Samuel Alito. Ginsburg, joined by Justices Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, dissented. Many subsequent election law decisions have been decided by similar coalitions, with predictable behavior on both sides of the debate.

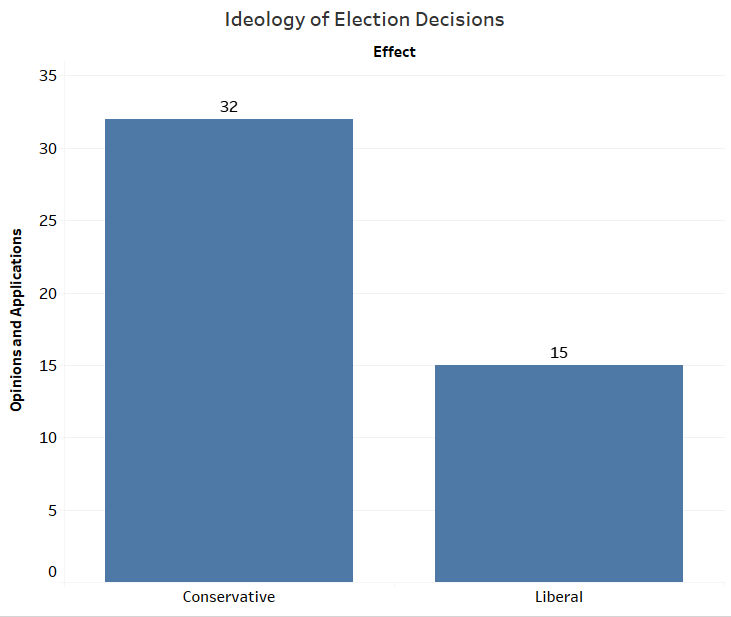

The direction of the tide of the court’s election law decisions is evident in the graph below, distinguishing the coded decisions since 2005 by ideological direction.

With a conservative majority in place, the court was well positioned to move in this direction when Roberts took the helm in 2005. Since then, the court’s decisions in election cases have been conservative more than twice as often as they have been liberal. With the recent confirmation of Justice Amy Coney Barrett and the new 6-3 conservative majority on the court, the justices should be even more well poised to uphold state restrictions on voting that curtail the overall voting population.

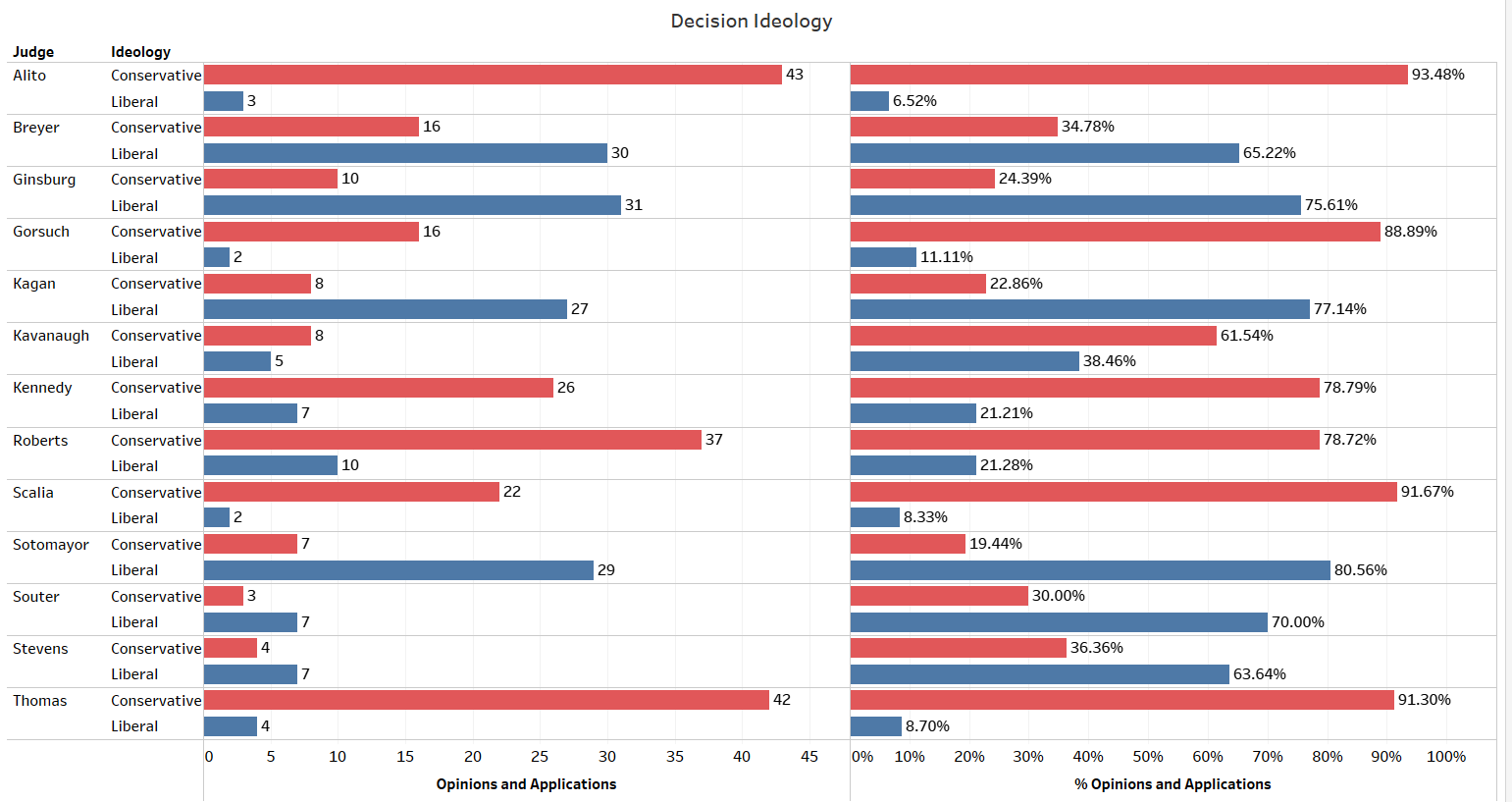

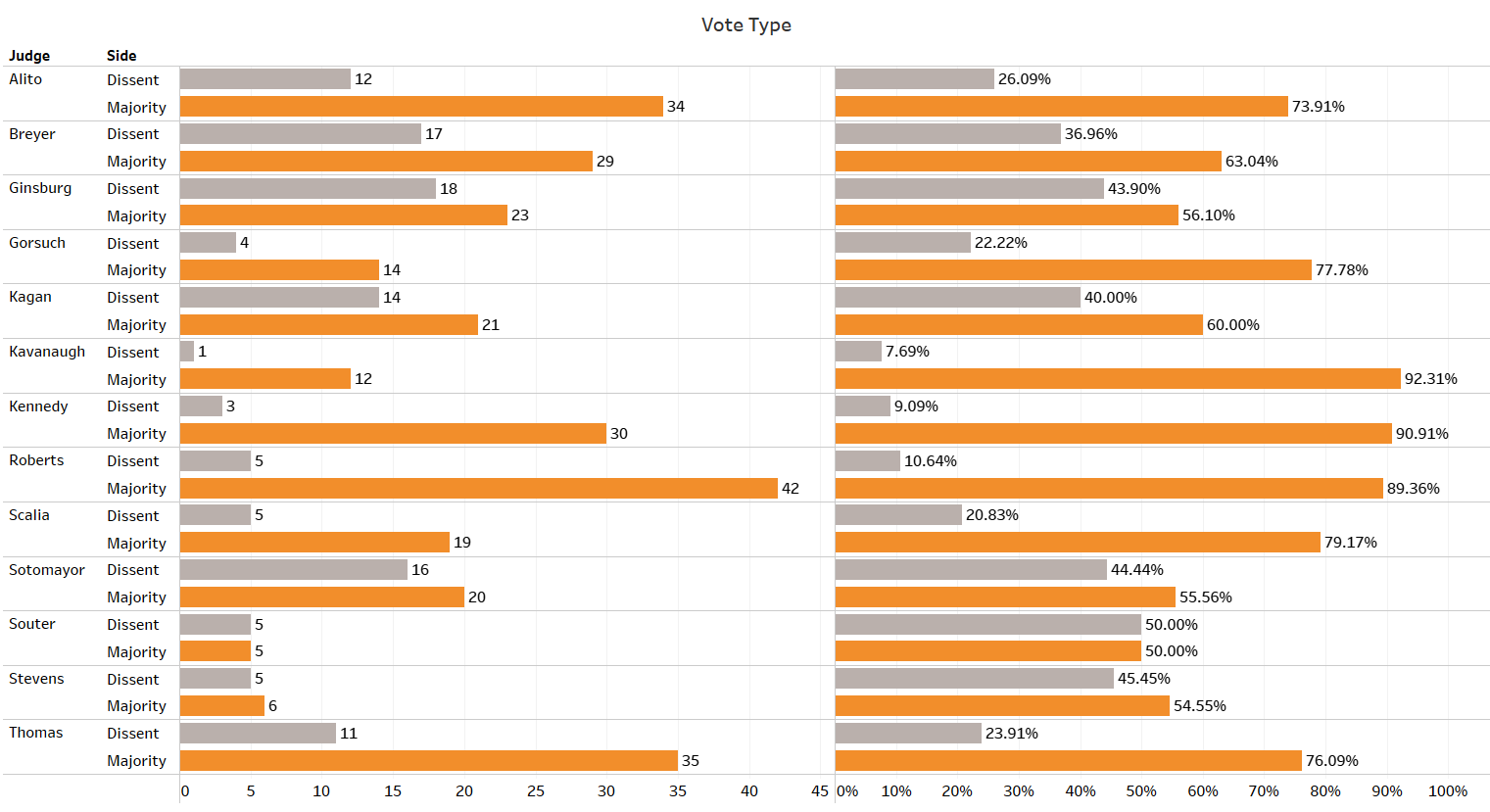

The justices’ votes in these cases reflect these deep entrenchments. The following graph breaks down each justice’s votes according to whether they were coded as conservative or liberal. The graph on the left shows the absolute count of election law cases in which a justice voted, while the graph on the right shows the corresponding percentages.

While the court’s conservative justices have tended to vote predominantly in a conservative direction, there is some variation in these votes. Roberts is the conservative justice with the highest number of liberal votes. His percentage of liberal votes matches nearly exactly that of Kennedy, who until his retirement in 2018 was often considered more moderate than Roberts. Alito, Thomas and Scalia all voted in a conservative direction over 90% of the time. Gorsuch is just behind, voting in a conservative direction 88.89% of the time.

The more liberal justices tended to vote in a conservative direction as well, at least a portion of the time. The justice with the highest proportion of liberal votes is Sotomayor at 80.56%. Sotomayor’s 19% of votes in a conservative direction is more than double the rate at which the most conservative justices voted in a liberal direction. None of the other liberal justices eclipse the 80% mark for liberal votes. Breyer has the highest fraction of conservative decisions of the liberal appointees still sitting on the court, with 65.22% of his decisions coded as liberal compared to 34.78% conservative.

When we look at the justices’ frequencies in the majority, we also see that the conservative justices were more often in the majority in these cases.

The three justices in the majority most frequently have been those with more moderate conservative ideology in these cases –Kavanaugh, Kennedy and Roberts. All three justices have been in the majority in around 90% of these cases. The other conservative justices have been in the majority at least 70% of the time, which is far more frequent than the liberal justices’ participation in the majority. By contrast, the two liberal justices most frequently in the majority have been Kagan and Breyer, both in the low 60% range. Although all justices hit 50% frequency in the majority, Justices John Paul Stevens and David Souter were exactly at 50%, while Sotomayor has been in 55.56% of majorities and Ginsburg was in 56.01%.

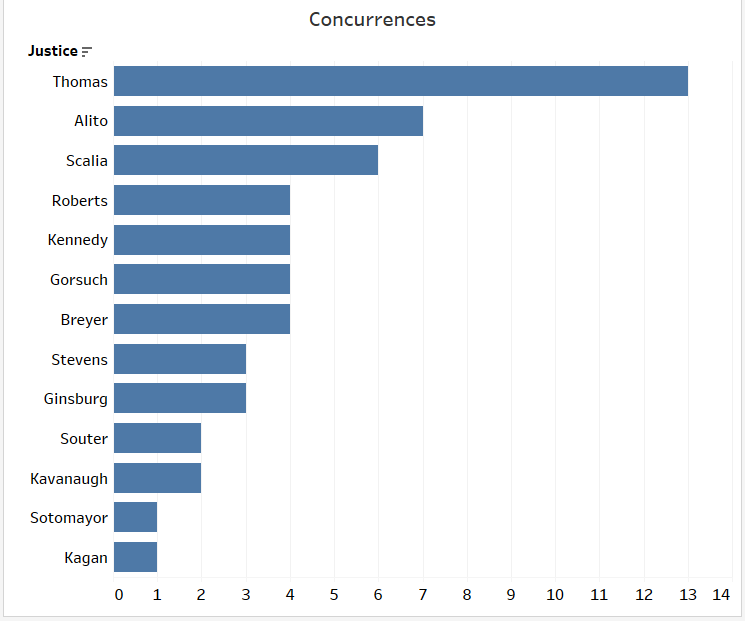

Justices in the majority in these cases have often had alternative views on case law than did the majority opinion writer, leading to a high number of concurrences. The concurrence counts including votes and authorship are below.

The more conservative justices make up the top part of this graph, with Thomas paving the way with 13 concurrences. Thomas is often ahead of the pack with concurrences in the court’s cases generally, but his lead does not tend to be this wide. Scalia and Alito are the other justices with at least six concurrences in these cases. The only liberal justice with at least four concurrences in these election cases is Breyer. Kagan and Sotomayor have each concurred only one time.

These statistics illustrate the growing divide among the court in election-related cases. The prolonged conservative majority might be one explanation for why we see liberal justices voting in a conservative direction more often than we see conservative justices voting in a liberal direction in these cases: Liberal justices might join a conservative majority in an effort to curb the scope of the outcome, or to form an alliance that might precipitate a more liberal decision in the future. Another explanation could be that the conservative justices simply skew further to the right on election issues than liberal justices do to the left.

Along with ideology, we see from the high level of concurrences that the justices each have distinct perspectives and flourishes they place on their decisions to indicate independent views of the various areas of election law. Ultimately, though, with the current court and the direction it is moving, we can expect to see additional state restrictions on voting rights upheld by a majority of the court.

This post was originally published on Empirical SCOTUS.