At Federalist Society convention, Alito says religious liberty, gun ownership are under attack

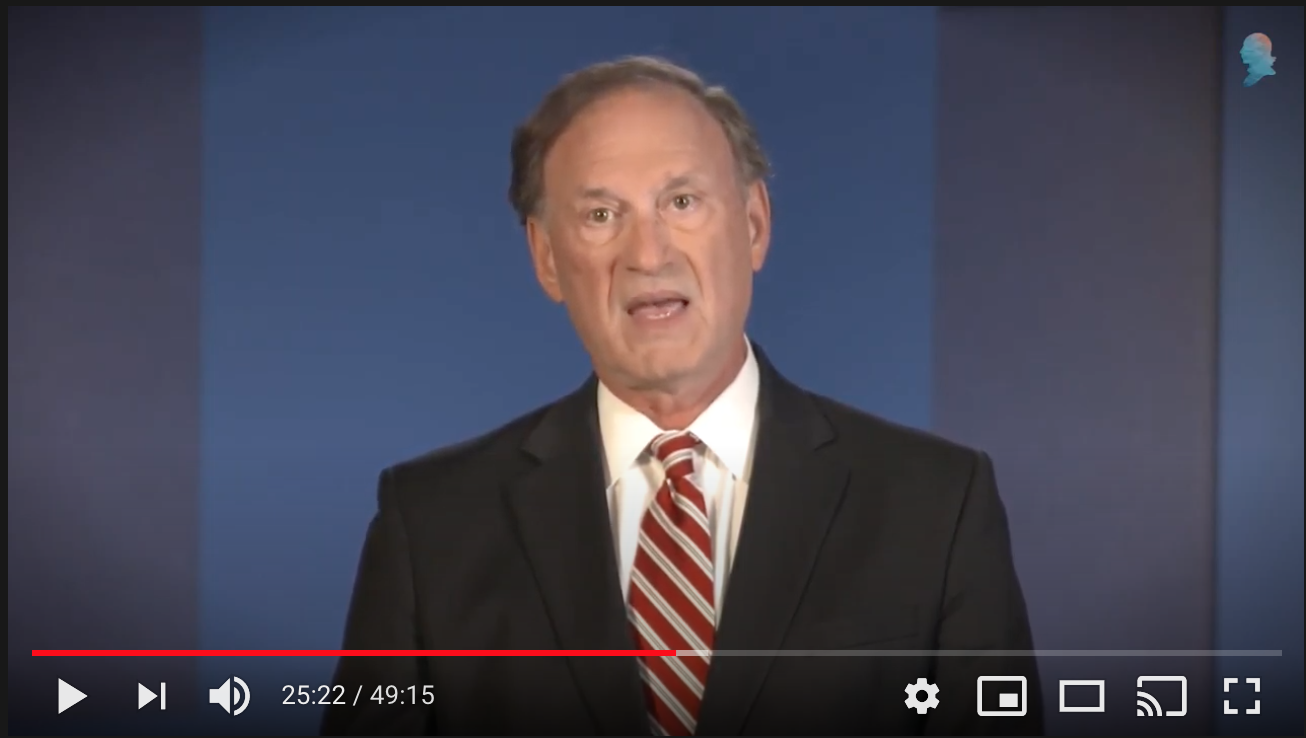

Justice Samuel Alito told the Federalist Society on Thursday night that two constitutional protections the First Amendment right to free exercise of religion, and the Second Amendment right to bear arms are rapidly becoming second-class liberties. Alitos keynote address at the group’s 2020 National Convention was the first public appearance by a Supreme Court justice (aside from the courts telephonic oral arguments) since the election.

Speaking to a virtual audience over video, Alito began on a lighter note. He urged the attendees, who at previous in-person conventions would have had a glass of wine, or two before the keynote, to partake in a beverage of their choice. He also invited any critics to throw rotten tomatoes all they like: You will only mess up your own screen.

Alitos tone quickly turned sober. In what became a theme of his remarks, he quoted from Justice Elena Kagan, who, while speaking at a Federalist Society event at Harvard Law School while she was dean, declared, I love the Federalist Society … but you are not my people. The point, Alito said, was to highlight the conservative organizations cultivation of spaces that are tolerant of opposing viewpoints, an acceptance he believes is now in short supply.

Turning from law schools to the judiciary, Alito criticized a measure proposed last year that would have barred federal judges from maintaining membership in ideological groups like the Federalist Society. We should all express our thanks to the 200 federal judges who signed a letter successfully opposing that measure, Alito urged, calling these judges defenders of free speech.

The COVID-19 pandemic was the subtext of this years convention. Alito used it as the lens for his speech. What has [the pandemic] meant for the rule of law? he asked. Stressing that he was not diminishing the virus threat to public health or the legality of COVID restrictions, Alito argued that the pandemic has resulted in previously unimaginable restrictions on individual liberty.

Take the plight of Calvary Chapel just outside Carson City, Nevada, Alito suggested. The church unsuccessfully petitioned the Supreme Court this summer to allow it to expand the size of its services in the face of a regulation by Gov. Steve Sisolak (D) that limited religious gatherings to 50 attendees while permitting casinos to operate at 50% of their capacity. In denying the chapels petition, Alito claimed, the court allowed [religious] discrimination to stand by a governor who chose to kowtow to his states biggest industry.

The Nevada case is indicative of a larger trend, Alito said: the dominance of lawmaking by executive fiat rather than legislation. By deferring to policymakers who are thought to implement policies based on expertise … in the purest form, scientific expertise, Alito cautioned that inflating executive power in the face of crisis opens the door for abuse of enshrined freedoms.

To Alito, religious freedom is most vulnerable of all. Religious liberty, Alito lamented, is fast becoming a disfavored right. The foremost example of this disfavor in the justices mind was the courts 1990 decision in Employment Division v. Smith, written by Justice Antonin Scalia, which cut back sharply on free exercise by establishing that religious groups are usually not entitled to faith-based exemptions from neutral, generally applicable laws. Alito lauded Congress for passing, with near unanimous support, the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 to push back against this very decision. The Supreme Court is considering whether to overrule Smith this term in Fulton v. City of Philadelphia. And the afternoon of Alitos speech, the Catholic diocese in Brooklyn asked the court for emergency relief from New Yorks coronavirus regulations similar to that previously sought by Calvary Chapel in Nevada.

Whether our society will be inclusive enough to tolerate those with unpopular religious beliefs, Alito said, is the question we now face. He listed a number of recent examples that have come before the Supreme Court, from the protracted campaign against the Little Sisters of the Poor, to the backlash against a Colorado baker who declined to provide a same-sex couple with a wedding cake, to a federal judges order blocking a federal regulation during the pandemic that required patients to make an in-person visit to a medical office to receive a pill used to induce abortion. Indeed, Alito claimed the situation is so dire that students, professors and employees today cant say marriage is a union between one man and one woman. The culture of censorship, he believes, should not have come as a surprise after the Supreme Courts 2015 decision in Obergefell v. Hodges striking down state bans on same-sex marriage.

Religion was not the only object of Alitos concern. The ultimate second-class right in the minds of some is the Second Amendment, the justice said. Looking to a case last term about firearm restrictions in New York City, Alito singled out a brief by five Democratic senators that suggested the courts decision to take the case was evidence of its capture by moneyed right-wing interests and threatened to restructure the court. The justices voted to dismiss the case rather than rule on the merits. Although he was not suggesting that the courts decision was influenced by the senators threat, Alito was concerned that it might be viewed that way by the senators and others who want to bully the justices. The senators brief was extraordinary, Alito continued. It was an affront to the Constitution and the rule of law.

Alito closed by paying homage to two justices. The first was Scalia, a founder of the Federalist Society and pioneer of the judicial philosophies of originalism (interpreting the Constitution as it was intended when it was written) and textualism (interpreting laws by their written text alone). The second was Kagan, whose statements that were all textualists now and were all originalists now signaled, to Alito, the profound influence of Scalias jurisprudence.

Whether referring to decisions under the penumbra of the pandemic, or to other cases from this past term, Alito warned that [w]e have seen the emergence of … erroneous aberrations from Scalias theories. The fight against these aberrations, he concluded, is not for the justices alone. In the end, there is only so much that the judiciary can do to preserve our Constitution, Alito said. Standing up for our freedom is a job for all Americans.

Posted in What's Happening Now