An advocate’s perspective on a justice who could never be outworked

on Sep 24, 2020 at 9:03 am

This tribute is part of a series on the life and work of the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

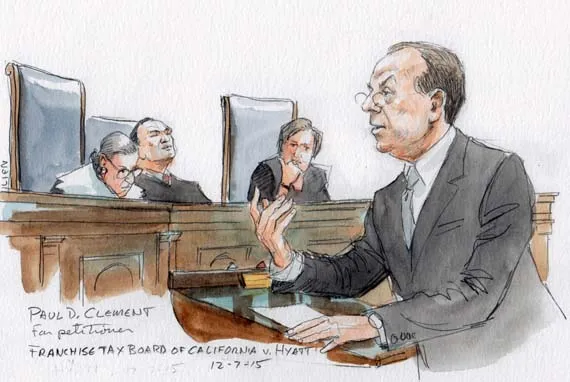

Paul Clement is a partner at Kirkland & Ellis. He served as U.S. solicitor general under President George W. Bush from 2005 to 2008, and he has argued more than 100 cases at the Supreme Court.

Over her four decades on the federal bench, Justice Ginsburg mentored scores of law clerks, inspired countless lawyers and non-lawyers, and fought tirelessly for equality. She also participated in thousands of oral arguments and read not just tens of thousands of briefs, but all or most of the appellate record in some 2,000 merits cases. I cannot claim to have had the kind of special relationship with the justice that her law clerks enjoyed, but I can tell you that from the perspective of an advocate, she was a special justice. Three things stand out.

First, she was a justice and a judge, but an advocate first (and not just chronologically). Justice David Souter put this point concisely in observing that Justice Ginsburg “was one of the members of the Court who obtained greatness before she became a great justice.” She was a path-marking litigator for equality for women and a keen legal tactician, as evidenced by the fact that, as often as not, her clients were men. She knew firsthand what it was like to argue a case before the Supreme Court. And, throughout all her decades of judicial service, she remembered what it was like to be an advocate facing the bench. As a result, she knew the advocates’ names, and asked her questions in a manner that was firm, but not sharp-edged; demanding, but still understanding. There was sometimes spin on the pitch, but it was never aimed at the advocate’s head. More than the other justices, she would on occasion quote directly from an advocate’s brief in her opinion when she thought a brief put a point concisely or felicitously. It was the ultimate hat tip, and a clear reflection that throughout her judicial career, she had an enduring appreciation for the advocate’s task and craft.

Second, she was the epitome of a thoroughly prepared jurist. When approaching the Supreme Court podium to begin an argument, the one thing an advocate could count on was that Justice Ginsburg knew the record, the whole record, and a lot more than the record. Her work ethic was legendary and evident, but not in a flashy way. While sometimes she would ask a direct question about where something was in the record, more often she asked a question that reflected a deep knowledge of how the case was litigated in the lower courts. She was a civil-procedure maven, and so those details mattered to her. Her mastery of the record impacted the way lawyers prepared for argument. The sure knowledge that Justice Ginsburg would be up late at night prompted many lawyers, this one included, to redouble their efforts. Nothing inspires a lawyer to work harder and longer than the prospect of facing a jurist who will not be outworked. Justice Ginsburg not only worked long into the night, but through a number of physical and medical challenges. Her last questions to me, in the oral argument in the Little Sisters case, were posed from her hospital bed. If the Supreme Court information office had not released that information, you would never have suspected it. She was as fully prepared as ever; firm, but clear, in making her point.

Finally, Justice Ginsburg’s famous friendship with Justice Antonin Scalia provides a critical model in these divisive times. I was introduced to their deep friendship early in my legal career while clerking for Justice Scalia. I clerked for him during Justice Ginsburg’s first term on the court. In fact, since I had clerked on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit the year before, Justice Ginsburg and I were “elevated” together, though I am quite sure that is not how she thought of it. Justice Scalia could not have been more delighted that his new colleague was his old colleague and dear friend. And he made that delight clear to his law clerks and made equally clear that no unkind word about the new justice would be tolerated in his chambers. Her opinions were another matter. Based on their service together on the D.C. Circuit, he was under no delusions that they would agree on all the cases, especially on the most contentious ones. To be sure, there would be a shared dedication to the legal craft and to proper grammar, and a shared love of opera and Marty’s cooking. But he knew that they would disagree on the substance of important legal issues. That would not get in the way of their friendship. Both justices could plainly distinguish between a dissenting opinion and the person who wrote it. Their long and enduring friendship was the very antithesis of today’s cancel culture where a person is dismissed socially because of dissenting views.

That first term together on the Supreme Court was the year the justices took their joint trip to India. Both came back with that iconic photograph of the two justices on the back of an elephant. Both justices prominently displayed that image that so aptly captured their relationship: two very different justices; one elephant. That image is part of their joint legacy, and it holds important lessons for admirers of either justice (or both), and for the whole nation in these divisive times.