Courtroom access: Where do we go from here?

Yesterday the Supreme Court heard oral argument in a set of cases that Deputy Solicitor General Jeffrey Wall, who argued on behalf of the federal government, described as “truly historic.” At issue was whether President Donald Trump could prevent the disclosure of his financial records, including his tax returns, to state prosecutors and congressional committees. In normal times, the disputes’ high profile would have resulted in long lines outside the court. But because of the COVID-19 crisis, no one had to sleep on the sidewalk on First Street NE. Anyone who wanted to listen to the oral argument was able to do so in real time, from the comfort of her couch or kitchen table. Indeed, many people apparently did tune in – although total numbers are hard to come by because the arguments were streamed on multiple media outlets, within a few hours of the argument session roughly 500,000 people had viewed the stream.

As our reporting in this series has made clear, the demand for seats at the high-profile (and many of the not-so-high-profile) oral arguments this term significantly outstripped availability. Getting one of the tickets distributed to members of the public without any connections – literally, the people who come in off the street – for these arguments requires a substantial commitment of time, with no guarantee of success.

It shouldn’t have to be this hard. And, fortunately, the experiences of state supreme courts and the highest courts in the United Kingdom and Canada – not to mention that of the Supreme Court itself during the COVID-19 crisis – show that there is another option: live-streaming arguments. None of the evils that are often cited as reasons not to allow live-streaming surfaced during the first week of live audio. There was no grandstanding by either the lawyers or the justices, and with the exception of an apparent errant toilet flush (which is not likely to occur again, and in any event obviously would not be a problem when arguments return to the courtroom), everything went off more or less without a hitch on the technological side. Having seen first-hand that live-streaming is not only possible but in fact a big success, the Supreme Court should not return to its pre-pandemic status quo, in which audio was never available in real time, and normally was not available until the Friday after an argument.

Even if the court continues with live audio (or, better yet, live video) after the pandemic is over, the lines will still remain, particularly on “big” argument days. People with a personal connection to the case or a sense of history will want to be “in the room where it happens.” (As Josh Blackman pointed out somewhat cynically, but also accurately, there is also a public relations value to being photographed coming down the steps of the court after the argument.) To that end, we propose some changes to the way in which the court handles seats for members of the public.

We’ll start, with apologies to economists everywhere, with the supply. The court should increase the number of seats set aside specifically for members of the public. Having only 50 of 439 seats in the courtroom – that is, just over 11 percent – in that category is, to put it diplomatically, less than optimal. More of the 186 “reserved” seats in the courtroom that are overseen by the Marshal’s Office at the Supreme Court should be allocated to the public as a general matter. Some of these could come from among the seats that are currently reserved for the guests of lawyers who are being admitted to the Supreme Court bar.

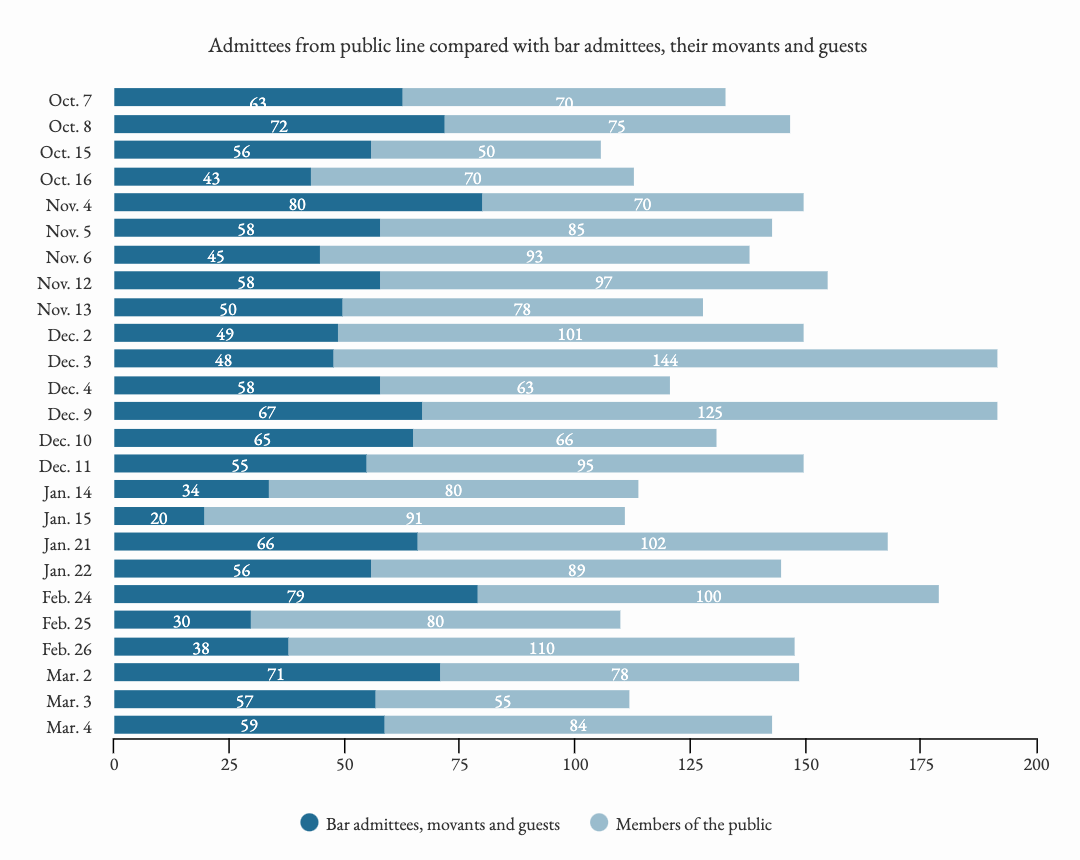

Being admitted to the bar in open court is a lovely tradition, and it is nice for lawyers to be able to bring a family member to witness the occasion. However, when a large number of lawyers are admitted on big argument days, allowing them to bring guests reduces the number of seats that might otherwise be available to the public – an especially undesirable outcome when many people are sleeping out on the sidewalk overnight in the hope of snagging a seat in the courtroom. As the chart below shows, the court admitted fairly large numbers of lawyers to the Supreme Court bar on several days when seats were in heavy demand, including the argument days for the Title VII cases (October 8), the Puerto Rico oversight board cases (October 15), the DACA cases (November 12) and the Appalachian trail cases (February 24).

The court could address this problem in a couple of different ways, which are not mutually exclusive. First, it could allow lawyers who are being admitted to the Supreme Court bar to bring guests, but then ask the guests to leave the courtroom after bar admissions so that members of the public can take their places. Second, it could limit the number of lawyers admitted on argument days and/or try to avoid scheduling large numbers of bar admissions on high-profile argument days. To be sure, many groups arrange to have their members admitted to the bar months in advance, long before the Supreme Court schedules its oral arguments. The Supreme Court could schedule those admissions on nonargument days, when the justices take the bench to issue opinions and conduct bar admissions.

More seats could be found for members of the public elsewhere in the courtroom as well. For example, spectators are rarely seated in the first row of the public section; doing so would provide roughly an additional 10 seats. If there are still people waiting in line for seats as 10 a.m. approaches, the court could also allow members of the public to fill other empty seats, such as the press seats in the hallway on the side of the courtroom. And on days when seats are in high demand, the court could create an overflow room – as it does for lawyers who do not get seats in the bar section – that would allow members of the public who do not get into the courtroom to listen to a live feed of oral arguments elsewhere in the building.

On the demand end, the court should start by banning line-standers, as it has in the bar line. Just as access to the courtroom shouldn’t depend on whether you know someone at the court who can get you a reserved seat, it also shouldn’t hinge on whether you have the funds to pay someone to stand in line for you, at a cost of $40 per hour or more. Although a ban on line-standers will mean fewer jobs for the men and women who fill those jobs, many of whom are homeless or formerly homeless, our observations of the bar line (as well as common sense) suggest that it will also mean less time in line for everyone. If you have to stand in line yourself, you may want to wait to get in line, so without paid line-standers, the line is likely to form later. And although it may be harder to enforce, this prohibition should extend to unpaid line-standers as well: Anyone who wants to see an argument should hold her own place in line. (This should not apply, of course, to the elderly or people with disabilities, for whom some seats in the courtroom should be set aside and distributed through the Marshal’s Office.)

The court has traditionally been reluctant to get involved in policing the public line: Officers normally don’t do much beyond handing out tickets at around 7:30 a.m. But other small steps by the officers could help to increase the perception of fairness – for example, handing out tickets or wristbands much earlier in the process (a step that many lawyers in the bar line might also welcome) to ensure that later arrivals don’t join the line and take a spot that should belong to someone who has spent many hours waiting. Blackman has recommended a much more dramatic step: Scrap the line system altogether in favor of a lottery. Such a system would not only address some of the social-distancing issues that the court is likely to face for many months to come, but (even if it included only some of the public seats) it would also give some members of the public more certainty – especially if they plan to travel to the court from out of town – that they will actually get a seat.

Finally, whatever steps the court may take to increase public access to the courtroom should be clearly explained on the Supreme Court website. Our reporting showed that currently, reliable information about how to obtain one of the public seats is difficult to find.

Last month Joan Biskupic of CNN reported on Justice Stephen Breyer’s “lively Zoom chat” with student at the United Nations International School. After discussing oral arguments, Biskupic recounted, Breyer invited the students to the Supreme Court to see for themselves. “You should come,” Breyer said to the students. “You should hear a case argued. I would love it.” Breyer is right that everyone should be able to see the Supreme Court in action. Under the current system, however, it’s far easier said than done. The suggestions that we have made in the second part of this post would allow more people (perhaps as many as 50 to 75 per day) to attend oral arguments, and it would make the process of waiting in line more equitable. These are not insignificant things. But those numbers are dwarfed by the number of people who could access – and, during the May 2020 argument session, apparently did listen to – the argument in real time through a live-stream. There’s no reason why the court shouldn’t continue with live-streaming after the COVID-19 crisis is over; there are over 300 million reasons why it should.

Katie Bart, Kalvis Golde, Tom Goldstein and Edith Roberts contributed editing, ideas and graphics to this post.

This post was originally published at Howe on the Court.

Posted in Courtroom Access