Courtroom access: The bar line and bar section

This post is based extensively on data collected by Casey Quinlan, Kalvis Golde and Katie Bart and analyzed and put into graphic form by Kalvis Golde and Katie Bart.

On many days at the Supreme Court, members of the general public hoping to obtain a coveted spot at oral argument are not the only ones waiting in line on the sidewalk outside the court. Especially on days when the court is hearing arguments in high-profile cases, the line for members of the Supreme Court bar lawyers who are admitted to practice before the court and therefore have access to special seats set aside for them often forms on the sidewalk near the northwest corner of the court in the early hours of the morning (or, on at least two occasions this term, the day before). Although securing one of these seats can also require a significant commitment of time, it is still generally easier to gain access to a seat in the bar section than one of the public seats, even if a substantial number of the bar seats are sometimes not available for the lawyers waiting in line.

On days when the bar line forms outside, the line moves inside to the first floor of the court building around 7:30 a.m.; on other days, the line forms inside the building after it opens. Either way, court officials eventually hand out tickets after checking to confirm that each person in line is a member of the bar a status available to attorneys who have a clean record after practicing law for at least three years, are sponsored by two bar members and pay a $200 fee and entitled to a ticket.

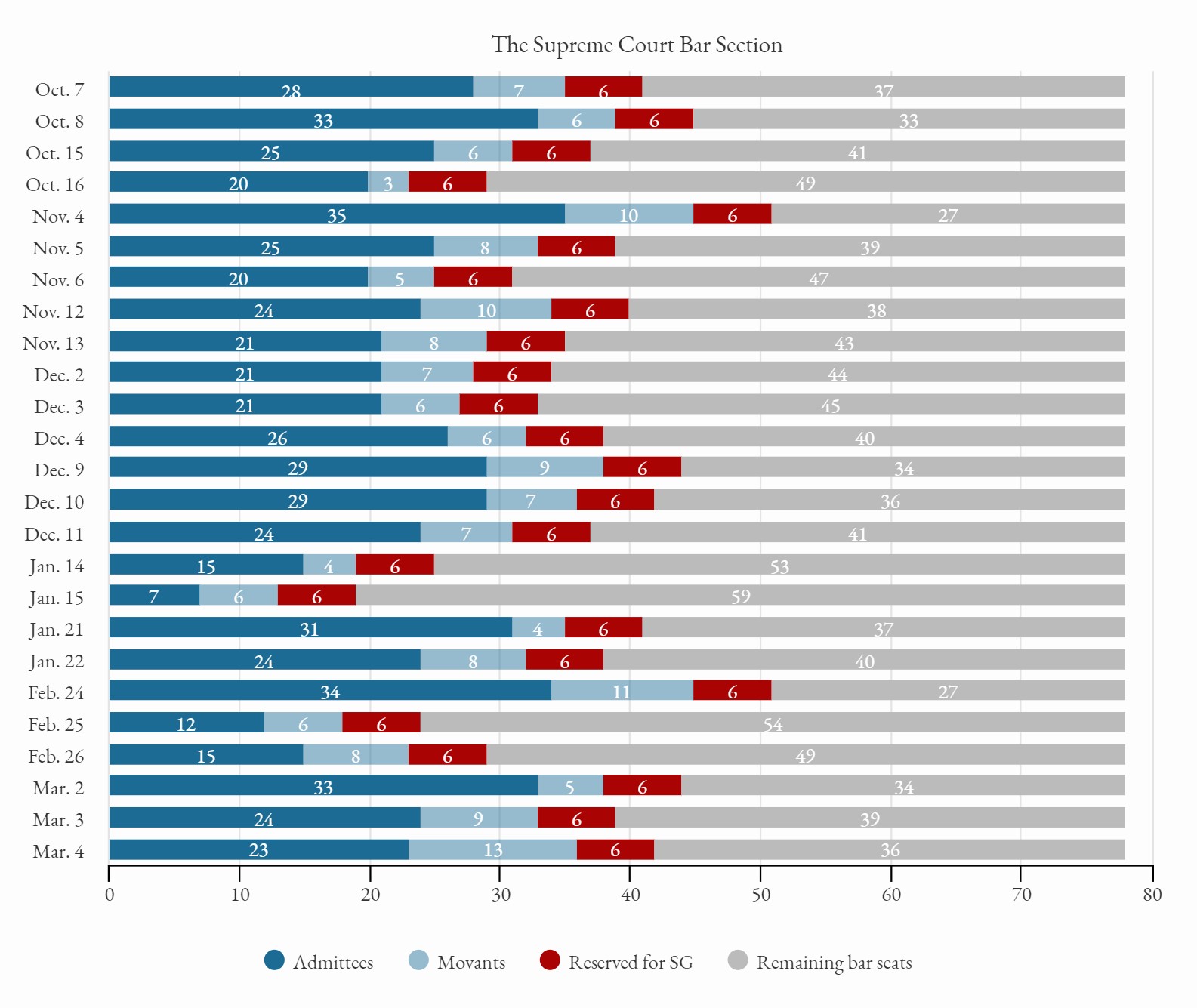

There are 78 seats reserved near the front of the courtroom, just behind the arguing attorneys, for members of the Supreme Court bar. However, on virtually all argument days, the justices also admit new lawyers to the Supreme Court bar, and these attorneys as well as the attorneys who appear before the justices to support their admission are also seated in the bar section without having to wait in line. Over the course of the term, the median number of seats occupied by lawyers involved in bar admissions was 32, with a maximum of 45 on February 24, when the Supreme Court heard oral argument in a case involving efforts to build a natural-gas pipeline under the Appalachian Trail. (Each attorney who is admitted to the Supreme Court bar is also allowed to bring one guest, who is seated in the public section.) Moreover, according to the courts Public Information Office, six seats in the bar section are normally reserved for lawyers in the office of the U.S. solicitor general.

Because of the number of seats that are often set aside in the bar section, fewer (and sometimes far fewer) than 78 seats are normally available to members of the Supreme Court bar. In a blog post, law professor Josh Blackman chronicled his experience waiting in the bar line before the justices heard oral argument in the challenge to the Trump administrations decision to end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program. Blackman was approximately 23rd in line but wrote that he was one of the last lawyers admitted to the bar section in the courtroom. There were 29 people admitted to the Supreme Court bar that day, with 10 different lawyers moving their admission which would mean a total of 39 seats (that is, half of the seats in the bar section) claimed in advance.

On days when the justices are hearing oral arguments in high-profile cases, the lines can still be long.

But although it isnt easy to get a seat on such days, doing so still generally requires less effort than getting a seat in the public line. For one thing, there are fewer members of the Supreme Court bar than of the general public. Another possible explanation is that bar members are not permitted to hire line-standers to wait for them, which reduces the likelihood of a race to the bottom: Lawyers may not get in line as early as they otherwise would if they know that they wont have to worry about competing with line-standers; moreover, because no one is hiring line-standers to wait for them, the line-standers arent arriving early to guarantee a place. Blackman, for example, arrived shortly after 3 a.m. to join the bar line for the DACA argument in November; a member of the public would have had to arrive around 8:30 a.m. the previous morning to get one of the tickets distributed at 7:30 a.m. on the morning of the argument. To get one of the public tickets distributed for the October arguments involving whether Title VII of the Civil Rights Act protects LGBT employees, you would have had to arrive nearly two days before the argument; in contrast, the bar line began to form at approximately 2 p.m. the day before the argument. And like the public line, the bar line is not always long: Beginning in December, the median number in the bar line at 9 a.m., when the court began to distribute tickets to the courtroom, was 31 people.

Perhaps most importantly, lawyers who strike out in the bar line have one big advantage that is not available to members of the general public: Even if they are not in the courtroom for the oral argument, they can still listen to it in real time. In the lounge at the Supreme Court reserved for bar members, the audio of the oral argument is broadcast over closed-circuit loudspeakers. In the pre-pandemic world, in which transcripts were not (and still are not) available for a few hours after an oral argument, and in which audio is not normally released to the public until the end of the week, this is a valuable perk of bar membership.

This post was originally published at Howe on the Court.

Posted in Courtroom Access