Courtroom access: No “performances,” just a “massive civics lesson” when supreme courts overseas live-stream their hearings

on Apr 30, 2020 at 3:48 pm

Editor’s note: On April 13, the Supreme Court announced that it would conduct 10 oral arguments via telephone conference on several days in May in cases whose oral argument dates had been postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and that it would make an audio feed available to the public through a media pool, providing real-time audio of oral arguments for the first time in its history.

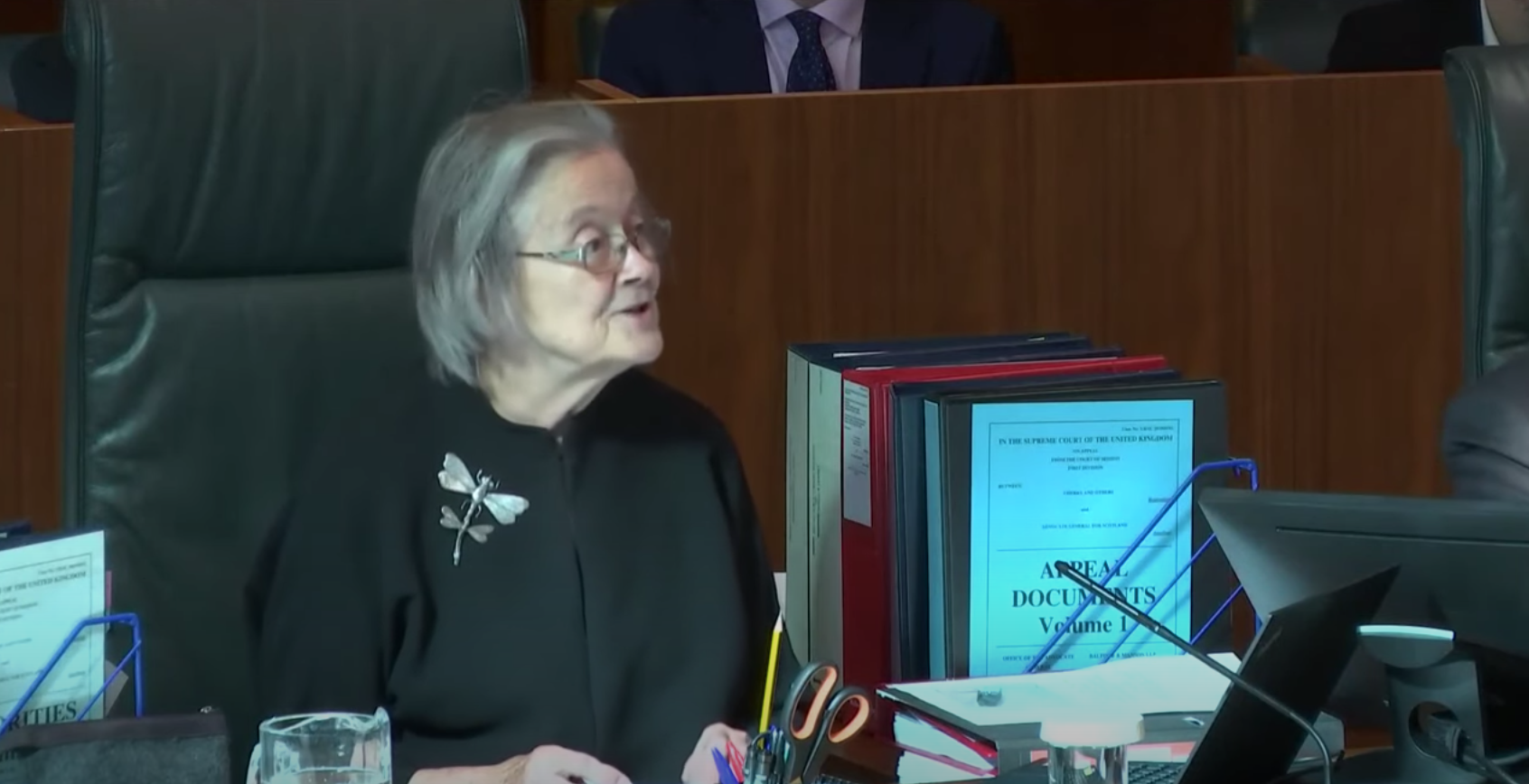

Last year the UK Supreme Court heard three days of argument on whether Prime Minister Boris Johnson acted properly when he asked Queen Elizabeth II to suspend the country’s parliament in the run-up to the deadline for Britain’s exit from the European Union. When the country’s highest court ruled that the government had shut down Parliament illegally, the BBC described the decision as “the worst possible outcome” for Johnson and concluded that it “challenges Britain’s unwritten constitution and the entire balance of power.” Some U.S. commentators compared the case to Marbury v. Madison, the 1803 ruling in which the U.S. Supreme Court established the principle that courts have the power to declare both laws and the actions of the executive branch unconstitutional. But there was at least one key difference between Marbury and the three-day debate over the decision to suspend Parliament: Thanks to the wonders of modern technology and the policy of the UK Supreme Court, millions of people watched the proceedings live through the court’s website – which recorded over four million hits on the first morning of the hearings alone.

The high level of interest in the UK Supreme Court proceedings may have been unusual, but the fact that the proceedings were live-streamed was not: Since its creation in 2009, the UK Supreme Court has routinely broadcast video of its proceedings. In 2015, that court announced a “video on demand” service to allow the public to watch past hearings. Lord Neuberger, the president of the court at the time, explained that the “archive will help people see the background to decisions made” in the court.

Closer to home, our northern neighbor’s highest court has had cameras broadcasting its proceedings for over 30 years. In a 2010 interview, Beverley McLachlin, then the chief justice of the Canadian Supreme Court, told an audience in the United States that although her court was initially “very wary” about televising its proceedings, over time she and her colleagues had become “just oblivious” to them. McLachlin downplayed concerns that televising the court’s hearings might lead to “grandstanding” by either lawyers or judges, concluding that “[n]obody is out there trying to put on a performance.” One year later, one of McLachlin’s colleagues on the court, Justice Ian Binnie, described a televised four-day hearing on Quebec’s right to secede as a “massive civics lesson.”

The United Kingdom and Canada are not alone in live-streaming their hearings. Brazil’s supreme court has made live video of its proceedings available for nearly two decades, including the justices’ deliberations on the cases after the lawyers make their presentations. The Supreme Court of Mexico also live-streams its sessions on the web. And the Israeli Supreme Court has recently begun to live-stream video of some (although not all) of its arguments as part of a one-year trial. On April 16, the court live-streamed its hearings for the first time, in a case involving whether the country’s government can collect cellphone data from individuals who have tested positive for COVID-19. Next week the court is scheduled to live-stream two days of oral argument in a case challenging the ability of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to form a new government when he is under indictment.

Live-streaming video of the proceedings in a country’s highest court may not be as widespread as it is in the state supreme courts here in the United States. However, the experience of the UK and Canadian Supreme Courts suggests that live-streaming has worked well – even in the kinds of high-profile cases that (at least according to some opponents of live-streaming) state supreme courts don’t necessarily encounter.

Katie Bart contributed substantial research assistance to this post, which was originally published at Howe on the Court.