Argument analysis: Justices grapple with Louisiana abortion law (Updated)

In 2016, the Supreme Court struck down a Texas law that (among other things) required doctors who perform abortions in that state to have the right to admit patients at nearby hospitals. In that case, Justice Anthony Kennedy joined the courts four more liberal justices in concluding that the law made it harder for women to obtain abortions while not doing anything, despite the states argument to the contrary, to protect the health of pregnant women. Today the Supreme Court considered the constitutionality of a similar law from Louisiana. But with Kennedy now retired, the laws fate seemed likely to hinge on the vote of Chief Justice John Roberts or perhaps Kennedys successor, Justice Brett Kavanaugh.

The dispute before the court this morning centered on the constitutionality of a 2014 law known as the Louisiana Unsafe Abortion Protection Act, which requires doctors who perform abortions in Louisiana to have the right to admit patients to a hospital within 30 miles of the place where the abortion is performed. In 2018, a federal appeals court rejected a challenge to the law, concluding that it did not impose a substantial burden on a large fraction of women.

The challengers doctors who perform abortions and an abortion clinic went to the Supreme Court last year, asking the justices to temporarily bar the state from enforcing the law until they could file a petition for review of the lower courts decision. A divided court agreed to stay the lower courts ruling, with Chief Justice John Roberts a dissenter in the Texas case joining the courts four more liberal justices in voting to stay the 5th Circuits ruling. In April, the challengers filed their petition for review; the Supreme Court granted that petition, as well as a related petition filed by the state, in early October.

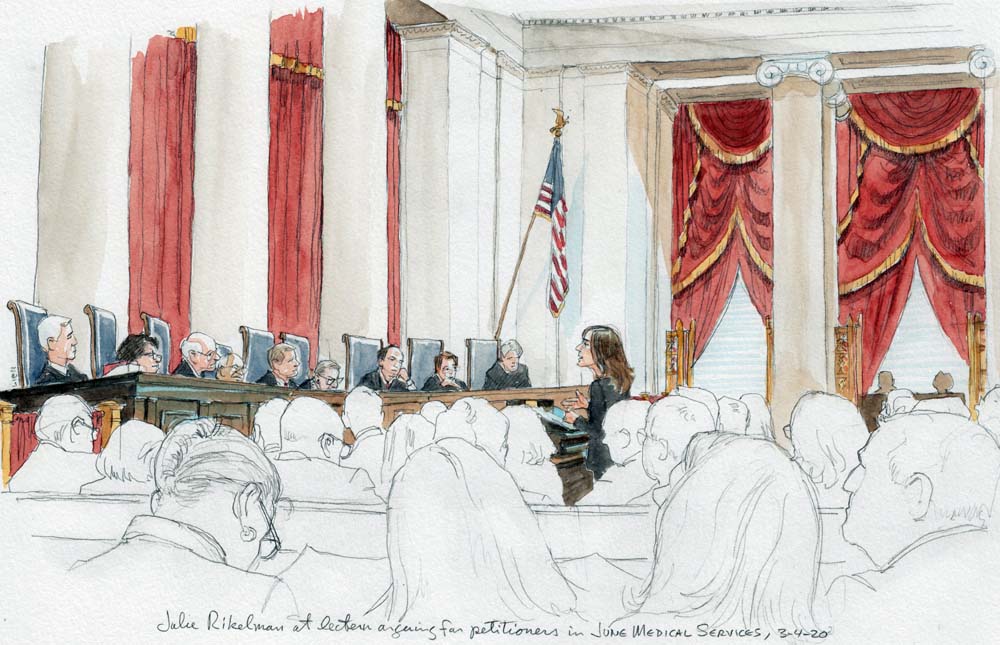

Arguing on behalf of the abortion providers, lawyer Julie Rikelman told the justices that this case is about respect for the courts precedent. The Louisiana admitting-privileges requirement, Rikelman emphasized, was expressly modeled on the Texas law that the Supreme Court struck down in 2016 and will do nothing for womens health. Nothing has changed, Rikelman continued, that would justify such a legal about-face from the courts 2016 ruling.

Rikelman quickly faced a barrage of questions from Justice Samuel Alito regarding whether her clients had a legal right to challenge the Louisiana law, known as standing, at all. Should a plaintiff be able to sue to protect the rights of others, Alito asked, when there is a conflict between the plaintiffs interests and the interests of the individuals whose rights the plaintiff seeks to protect? When Rikelman responded that a plaintiff should be able to sue when she is directly regulated by the law at issue, Alito was incredulous. Thats amazing, he told Rikelman.

Rikelman pushed back, arguing that the state had waived its ability to challenge her clients right to sue. She received an assist from Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who observed that the state hadnt raised the issue until its cross-petition in the Supreme Court. The abortion providers might have joined a patient or two if the state had flagged the question earlier, Ginsburg indicated.

Justice Stephen Breyer was also uninclined to agree that the abortion providers lacked standing to sue on behalf of their patients. Breyer announced that he had found at least eight cases in which the Supreme Court had allowed abortion providers to sue on behalf of their patients. Why, he asked Jeffrey Wall, the deputy U.S. solicitor general who argued on behalf of the federal government as a friend of the court supporting Louisiana, should we depart from what was pretty clear precedent? Wall answered that the Supreme Court has never signed off on the right to sue for abortion providers who, like the providers in this case, have an actual conflict of interest.

Significantly, although Justices Clarence Thomas (who argued in his dissent in the Texas case that the abortion providers lacked a right to sue) and Neil Gorsuch did not ask any questions, neither Roberts nor Kavanaugh seemed to express any interest in the standing question, suggesting that there may not be five votes to dismiss the case on this ground.

Roberts repeatedly returned to the question of how the justices should apply their 2016 decision in the Texas case, Whole Womans Health v. Hellerstedt, to this case. Is the inquiry under Whole Womans Health, he first asked Rikelman, a factual one that has to be conducted state by state? For example, Roberts posited, the district court would examine the availability of doctors and clinics in a particular state, so that the results could be different in different states. Roberts view on this question could be important: If he concludes that the Whole Womans Health inquiry is a factual one that is conducted state by state, it could allow him to find some daylight between the Louisiana law and the Texas law that the court struck down four years ago.

Rikelman acknowledged that the burdens of a law may vary according to the law at issue, but she stressed that an admitting-privileges law has no benefits and is therefore more likely to be a burden in every state.

Kavanaugh then pressed Rikelman as well. If the admitting-privileges law did not have any effect that is, if all the doctors could get admitting privileges would the law still be an undue burden and therefore unconstitutional? Rikelman conceded that such a case would be very different, but she reiterated that there would still be no benefit to the law.

Roberts had a similar question about how to apply Whole Womans Health for Elizabeth Murrill, Louisianas solicitor general. Do you agree, he asked Murrill, that a courts inquiry into the benefits of an abortion law will be the same in each state? Murrill disagreed. A state could show that a law has more benefits depending on the state, she answered.

Much of the rest of the argument was spent discussing whether Louisianas admitting-privileges law actually has any benefits, and whether the states abortion providers had really made an effort to obtain privileges at nearby hospitals. Ginsburg described the requirement that an abortion provider obtain privileges at a hospital within 30 miles of the clinic where she performs abortions as odd. Most abortions dont result in any complications, she suggested, and even if a woman who has had an abortion needs to go to a hospital, she will go to the hospital that is closest to her home, not the hospital closest to the abortion clinic. These laws, Ginsburg asserted, will always put barriers to abortion while serving no benefit.

Wall resisted Ginsburgs contention that the 30-mile requirement serves no purpose. All admitting-privilege requirements have some geographical limit, he began. And even if there was no evidence in the Texas case that women who needed to be hospitalized were transferred to the hospital from the clinic, there is such evidence in this case even if we dont know how often it happens, Wall said.

Justice Elena Kagan, who asked relatively few questions, posited that the admitting-privileges requirement does not necessarily guarantee that doctors who perform abortions are qualified to do so. In Whole Womans Health, she told Murrill, the court held that the state cannot say it is imposing an admitting-privileges requirement for credentialing reasons if hospitals are denying applications for admitting privileges for other reasons for example, because doctors dont admit enough patients to the hospital or because doctors perform abortions.

But Wall countered that in a case like this, when the law has not yet gone into effect, all the challengers ought to have put their applications where their mouths are: They should have at least applied for admitting privileges before going to court to block the law from being enforced, so that the court could know for certain whether they really cant get admitting privileges. And Murrill was even stronger, telling the justices that there was evidence that the challengers who had applied for admitting privileges had sabotaged their own applications.

Alito appeared sympathetic to this argument. Referring to one doctor, known only as Doe #2, Alito suggested that it would be against the doctors own interests to make a super effort to get admitting privileges, because hed be defeating his own claim. Doe #2 has previously had admitting privileges at a hospital in Shreveport, Alito noted, but he didnt apply for privileges again because it was a Catholic hospital (and he presumably believed that he wouldnt obtain them), but another doctor, known as Doe #3, did obtain admitting privileges at that hospital.

At one point, Justice Stephen Breyer appeared to throw up his hands. Were not going to solve this at oral argument, he told Murrill. But the justices will meet to vote on the case later this week, and a decision is expected by summer.

This post was originally published at Howe on the Court.

Posted in Merits Cases

Cases: June Medical Services LLC v. Russo, Russo v. June Medical Services LLC