Empirical SCOTUS: About this term: OT 2019

Even though briefing is not complete in all the cases that will be argued before the Supreme Court this term, interest in the court’s cases is at an apex. There was a lot of hype leading into this term, as it is the first full term for the current Supreme Court, whose bench has been largely in flux since Justice Antonin Scalia’s sudden passing in the middle of the 2015 term. Increased media coverage has also put a spotlight on the court’s integral role in resolving high-profile issues, such as the potential release of President Donald Trump’s tax returns and the legality of the president’s immigration policy.

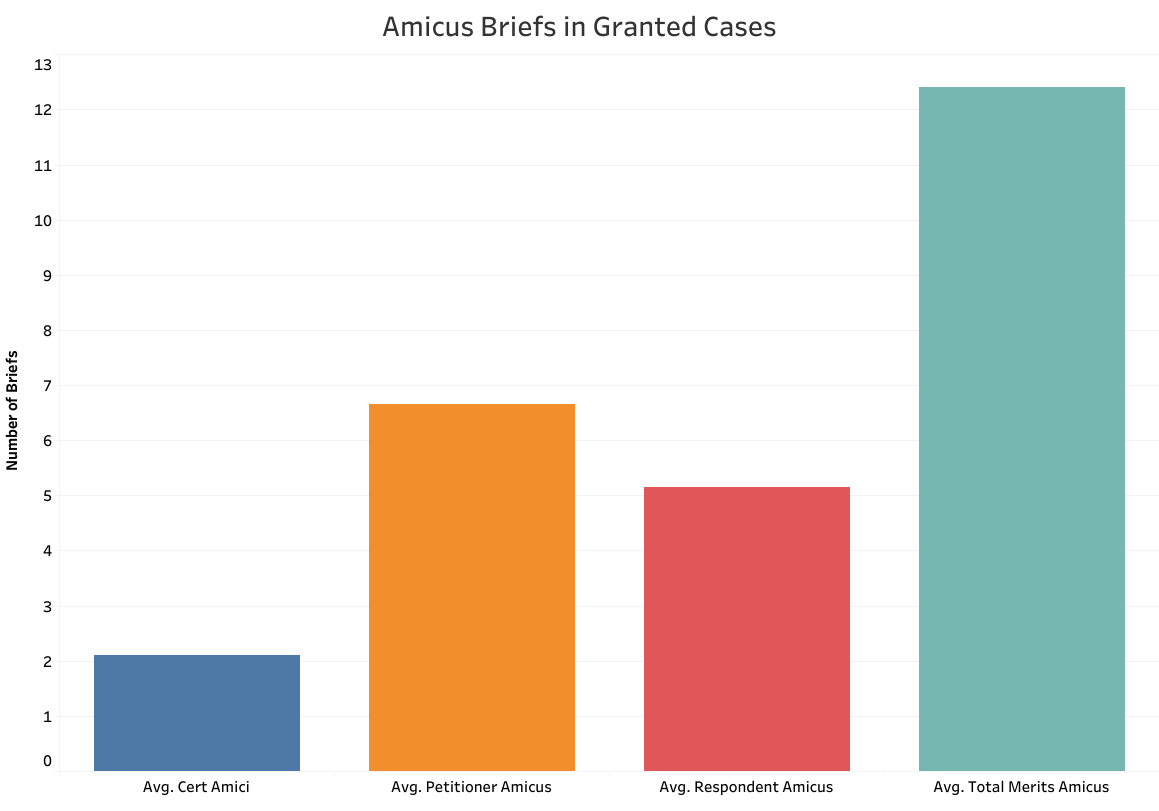

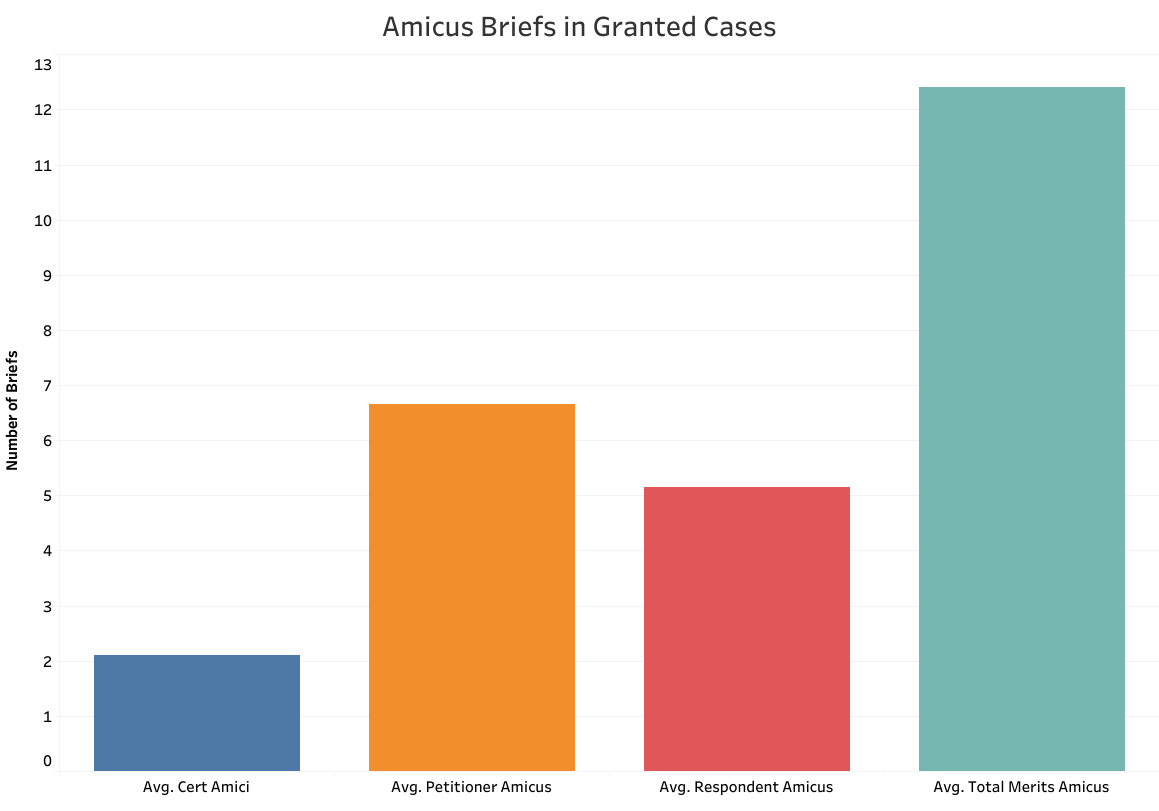

One measure of public interest in a given case is the number of amicus briefs filed. Amicus briefs filed on the merits after cases are granted can be differentiated from amicus briefs filed in support of cert petitions (which show groups’ interest in the court deciding particular issues). Cases this term have averaged high numbers of both cert-stage and merits-stage amicus briefs. Specific trends are also evident in the justices’ choice of cases for this term. These analytic measures provide insight into attorneys’ strategies for convincing the court to hear their cases and into the justices’ interests in taking them.

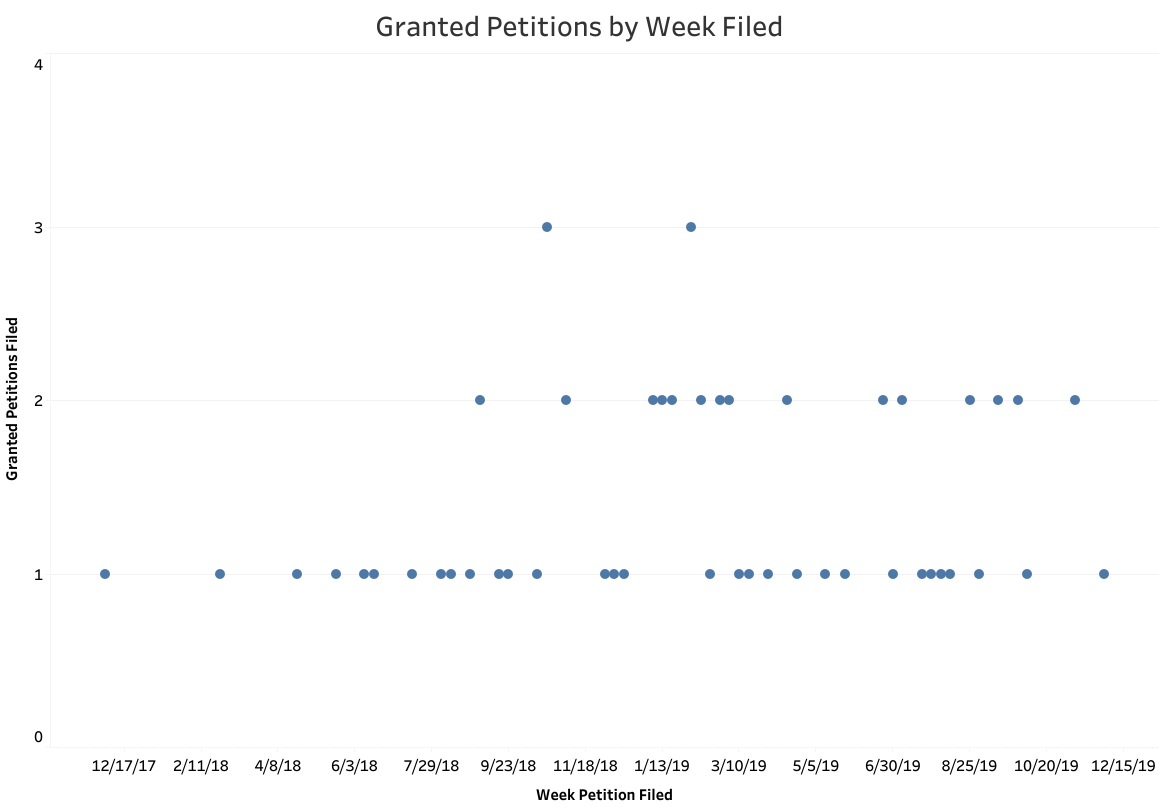

The chart below shows how the justices have granted cert petitions in clusters so far this term.

The most granted petitions filed within the same week, three, were filed during the weeks of October 21, 2018, and February 3, 2019. The court also granted two petitions filed during the same week for several weeks between October 21, 2018, and February 3, 2019, highlighting the importance of strategically timed petition filing.

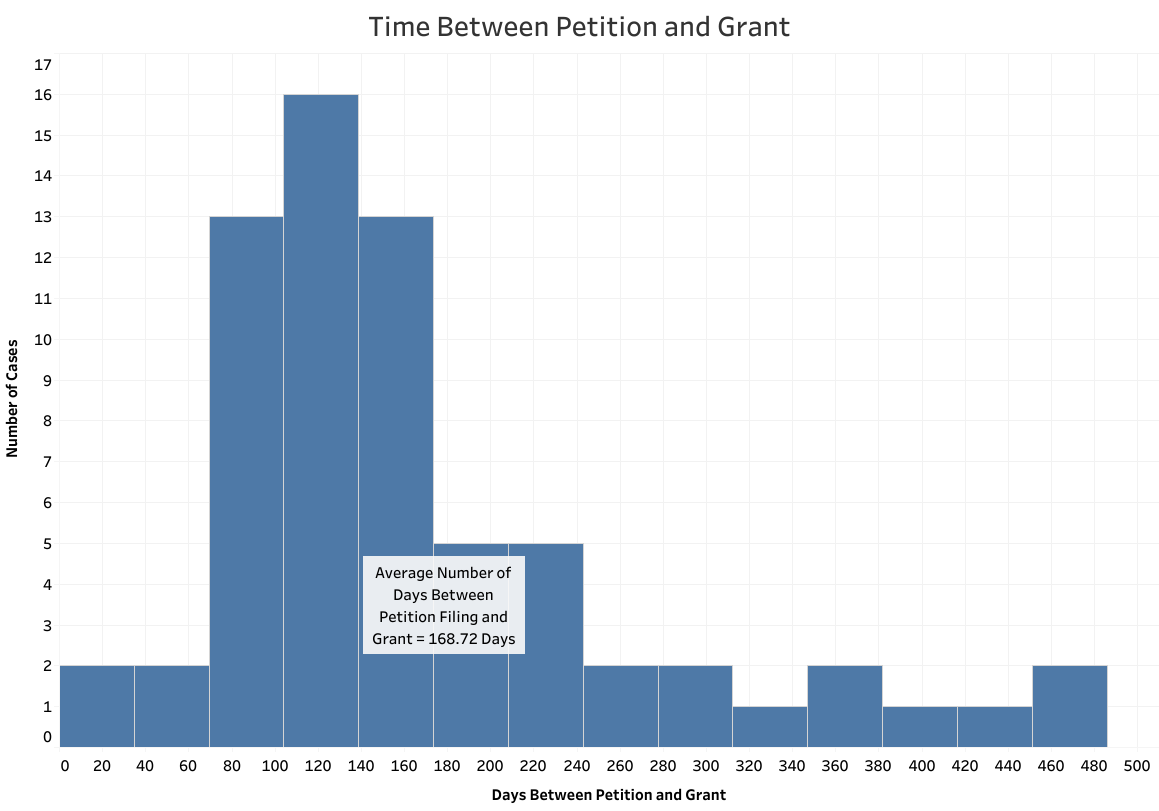

The justices took an average of 168.72 days from the filing date to grant petitions for argument this term. (It’s worth noting that this time period can be drawn out if the respondent requests an extension to file their brief or the solicitor general is invited to share the views of the federal government).

A total of 42 petitions, the majority of those granted for argument this term, were granted in a window of 70 to 170 days from the time the petitions were filed. Two cases, both involving whether the president can prevent the release of his tax returns, took the justices fewer than 30 days to grant. On the opposite end of the spectrum, Opati v. Republic of Sudan — looking at whether the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act applies retroactively, thereby permitting recovery of punitive damages under 28 U.S.C. § 1605A(c) against foreign states for terrorist activities occurring prior to the passage of the current version of the statute — was granted 483 days after the petition for cert was filed.

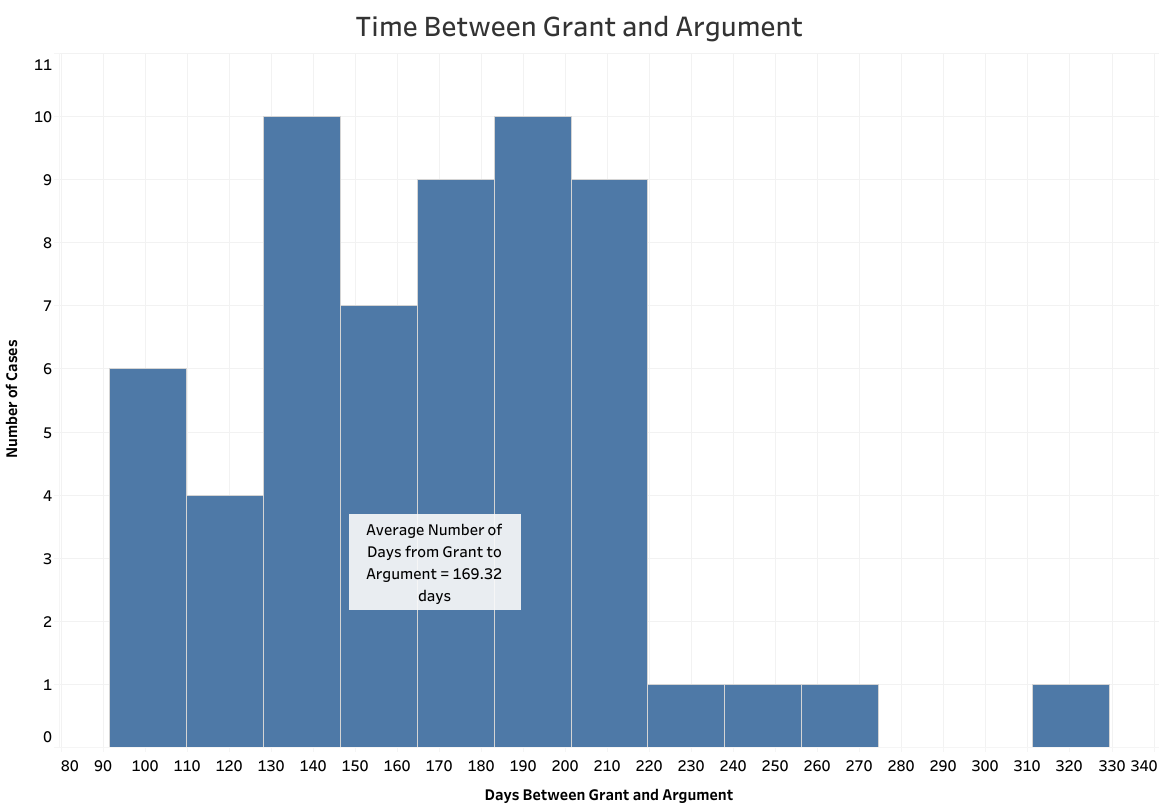

For most cases, more time elapsed between cert grant and oral argument than between petition filing and the day the justices granted the petition. Still, the opposite was true for a nontrivial number of cases, 22. The following figure shows the distribution of time between petition grant and oral argument for cases granted for argument this term.

The justices scheduled oral argument in 10 cases for between 120 and 140 days from cert grant and in 10 other cases for between 180 and 200 days from cert grant. Looking at the ratio between the length of time from petition filing to cert grant and from cert grant to argument date, the case with the smallest ratio was McKinney v. Arizona. This case was granted 109 days after the petition was filed and scheduled for oral argument 184 days after the cert grant, for a ratio of .59. This can be compared to Google v. Oracle, in which the justices took 409 days to grant the petition after filing and scheduled oral argument in the case 176 days after cert grant, for a ratio of 2.32.

Cases this term have averaged a high number of amicus briefs both at the cert stage and on the merits. Case averages by amicus party type are shown below.

Merits cases have averaged just over 12 amicus briefs so far this term, with petitioners averaging 6.66 briefs and respondents averaging 5.15 briefs. R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes Inc. v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission has the most merits amicus filings with 86, followed by June Medical Services LLC v. Gee with 70 and Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia with 68 (for a deep dive into cases with a large number of amicus briefs in previous terms, see this paper). Because we don’t have all the amicus filings in all cases for this term, the averages in the chart above as well as this ranking of cases with the most amicus filings may shift before the term is complete.

For cases already argued and with at least one amicus brief filed on each side, the case with the most amicus briefs filed on behalf of petitioners relative to those filed on behalf of respondents is the consolidated case of Maine Community Health Options v. U.S., with nine petitioner amicus briefs and one respondent amicus brief. The case with the most respondent amicus briefs relative to petitioner amicus briefs, also at nine to one, is U.S. v. Sineneng-Smith.

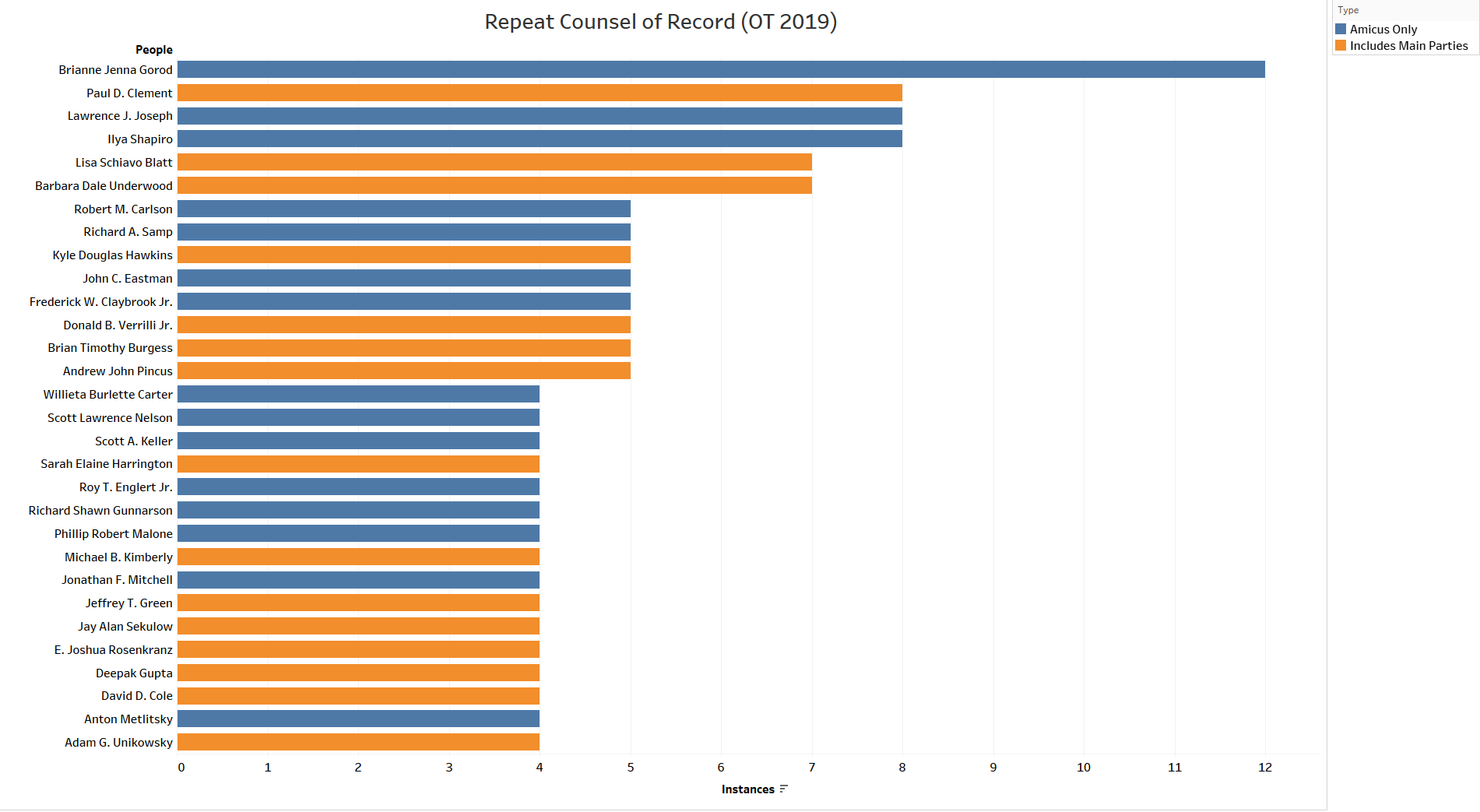

The amicus filings so far this term include many filed by repeat players who have been active in Supreme Court litigation for years. A look at counsel of record for all merits-stage briefs, both for amici and for parties to the dispute, filed in cases this term bears this out.

So far, Brianne Gorod of the Constitutional Accountability Center is counsel of record on the most briefs, with 12. She is followed by Paul Clement from Kirkland & Ellis, who is counsel of record on a mix of parties’ briefs in cases he argued (or will argue) and amicus briefs; Lawrence Joseph, who regularly files amicus briefs on behalf of various groups (for example); and the Cato Institute’s Ilya Shapiro — all counsel of record on a brief in nine cases. Just behind these three with eight briefs apiece are New York solicitor general Barbara Underwood and Williams & Connolly’s Lisa Blatt.

The court’s decisions in many cases this term are highly anticipated. The large presence of amicus filers as well as veteran attorneys representing parties is a testament to this. Based on the justices’ voting patterns in highly anticipated decisions over the last few terms, we can expect several of these cases to be decided by 5-4 votes along ideological lines. By the end of the term we will know with more clarity whether these ideological divisions will persist, or whether this court will rise above the ideological fray in a manner articulated by Chief Justice John Roberts on multiple prior occasions.

This post was originally published at Empirical SCOTUS.

Posted in Empirical SCOTUS