Empirical SCOTUS: Activist or restrained, the current court’s movement is often directed by the chief justice

At the helm of the Senate impeachment trial, Chief Justice John Roberts is engaged in politics in a manner distinct from any other role he has or will play on the Supreme Court. At the impeachment trial Roberts presides over the Senate, mainly ruling on procedural issues, but he has also shown a willingness to exert control of the proceedings when he feels it is necessary. In this political thicket, the chief justice is working within a checks and balances framework that entangles the three branches of government. This type of entanglement between branches is deliberate in the case of impeachment of a president but divergent from what is often expected of Supreme Court justices. During their tenure on the court, the justices are expected to stay out of politics. Although studies dating back to the 1950’s show that the court does not really avoid politics at all, there are doctrines created to keep the justices out of politics and to ensure they decide actual “cases or controversies” as Article III of the Constitution requires.

The court traditionally follows a set of rules under justiciability doctrines so that the justices are focused on actual controversies that do not pertain to “political questions,” which are not the province of the court. (The court’s decision in Baker v. Carr (1962) elaborates on the political question doctrine.) The justices sometimes mention these principles in order to explain why they are not relevant. At other times, the court looks to these principles in an attempt to clarify when they apply. In Baker, for instance, the court cited Coleman v. Miller (1939) for the proposition that, “[i]n determining whether a question falls within [the political question] category, the appropriateness under our system of government of attributing finality to the action of the political departments and also the lack of satisfactory criteria for a judicial determination are dominant considerations.”

The court has applied these principles in cases as recent as last term’s Rucho v. Common Cause, in which Roberts wrote for the majority:

Excessive partisanship in districting leads to results that reasonably seem unjust. But the fact that such gerrymandering is “incompatible with democratic principles,” Arizona State Legislature, 576 U. S., at ___ (slip op., at 1), does not mean that the solution lies with the federal judiciary. We conclude that partisan gerrymandering claims present political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts.

The court, however, has been criticized by the left and the right in recent years for taking on cases that could be left to the political branches of the federal government. These criticisms may recur, as the court plans to hear a case this term that examines the voting rules for members of the Electoral College. Suffice it to say, the line between justiciable questions and those beyond the province of the court is not crystal clear.

Nonetheless, the court regularly brings up rules of justiciability both in oral argument and in its opinions. Sometimes, as in Rucho, the justices invoke the doctrines to eschew decisions on the merits, while often the justices explain why the doctrines do not impede the court from ruling on the merits. This post examines instances in which the justices have discussed aspects of justiciability, including mootness, ripeness, standing, political questions and justiciability generally, between the 2017 and current Supreme Court terms.

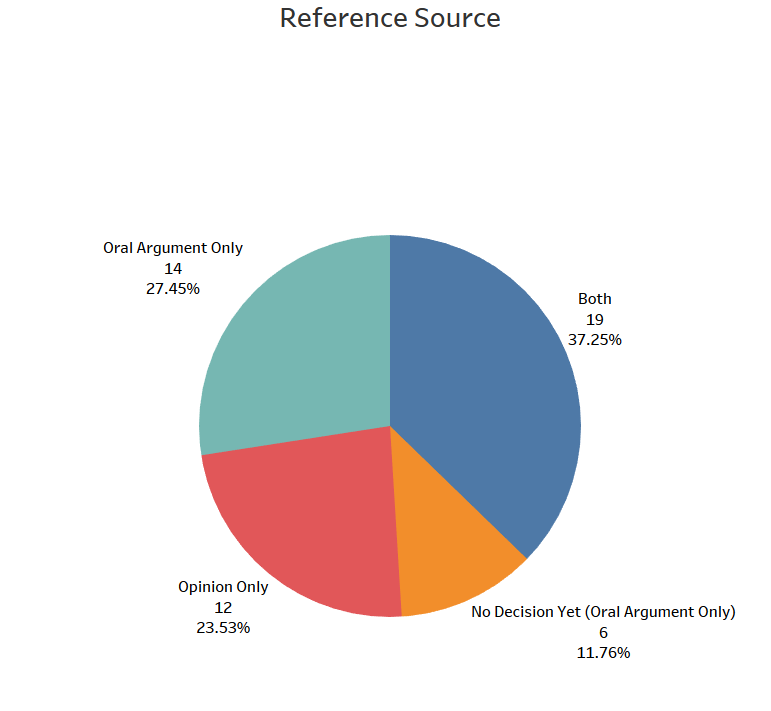

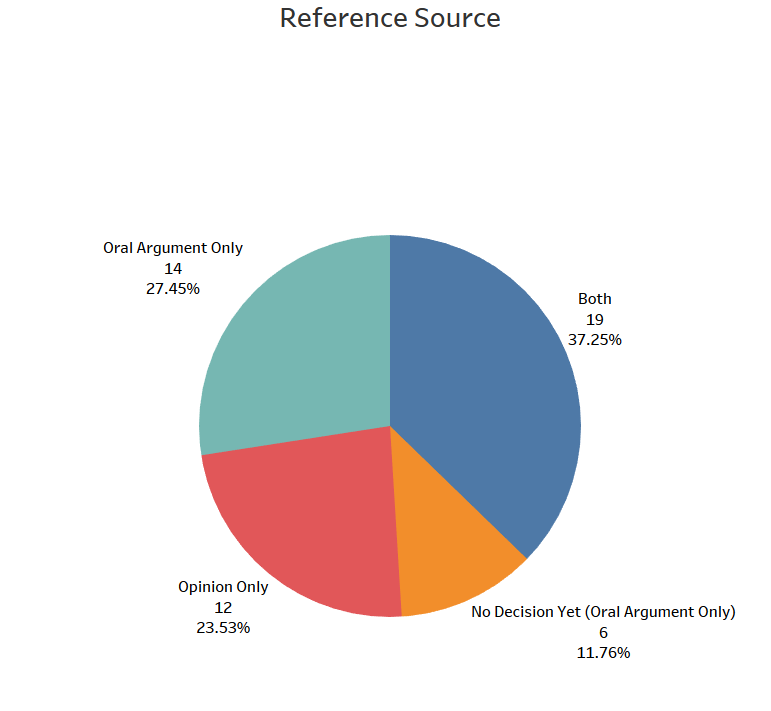

These doctrinal principles arose in 51 cases since the beginning of the 2017 term. The following chart splits the cases by whether the principles arose in the opinion, oral argument or both, or in an oral argument for a case yet to be decided.

Most often these references occurred both during oral argument and in at least one opinion in a case, but in many instances the reference came up in either oral argument or an opinion but not both. This means that justiciability might have been an issue resolved at oral argument or an issue that was missed at oral argument but that came to light before the decision was released.

Oral arguments

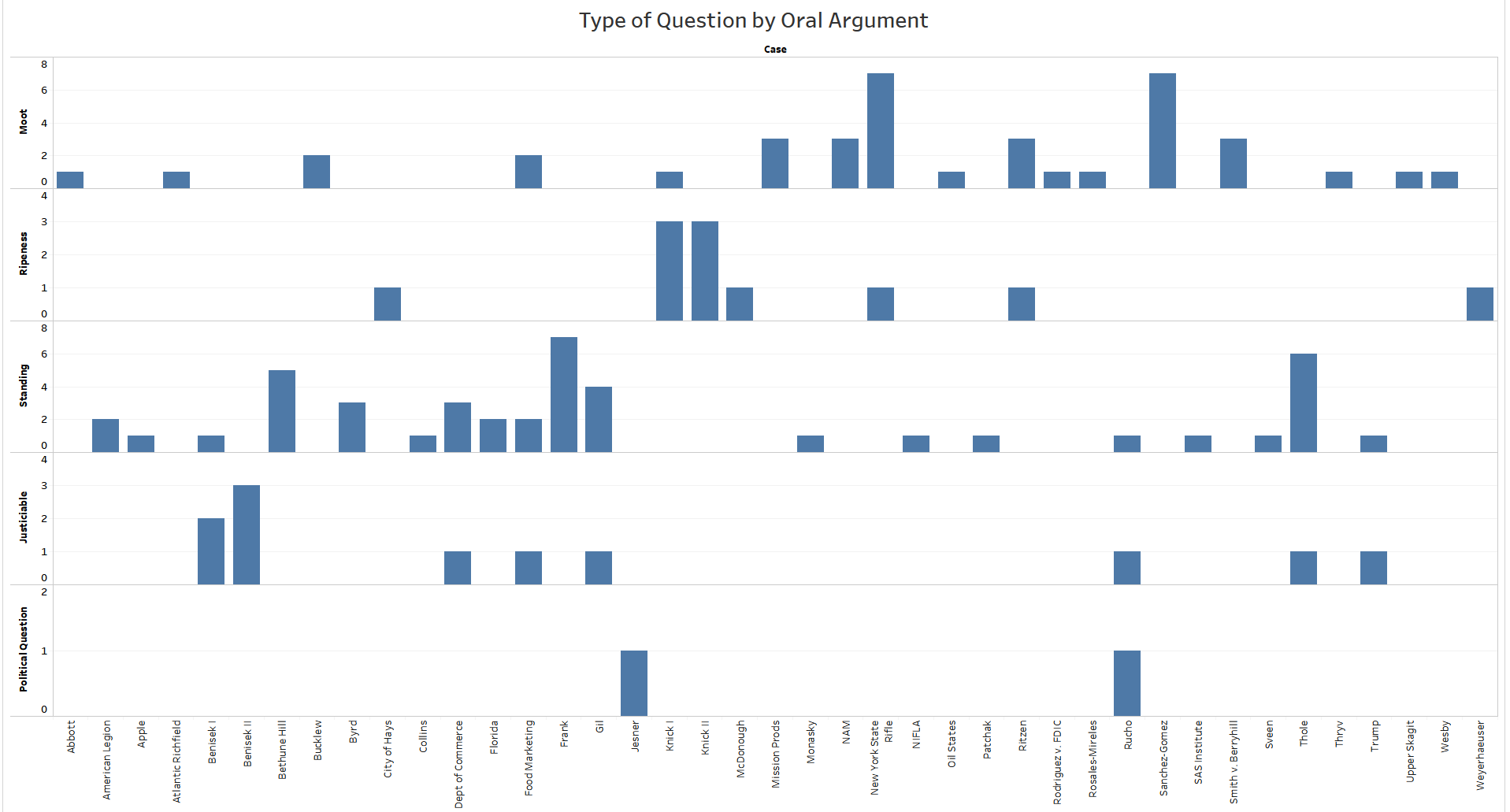

Looking first at oral arguments, we can see several trends when the justices’ questions are broken down by case and area of justiciability.

Standing and mootness questions were most prevalent, followed by questions related to general justiciability and ripeness, and lastly those related to political questions. Mootness came up most often (six times) in both New York State Rifle & Pistol Association Inc. v. City of New York, New York and United States v. Sanchez Gomez. Standing came up most often in arguments in Frank v. Gaos. Discussion of the political question doctrine only arose in the arguments in Jesner v. Arab Bank and Rucho.

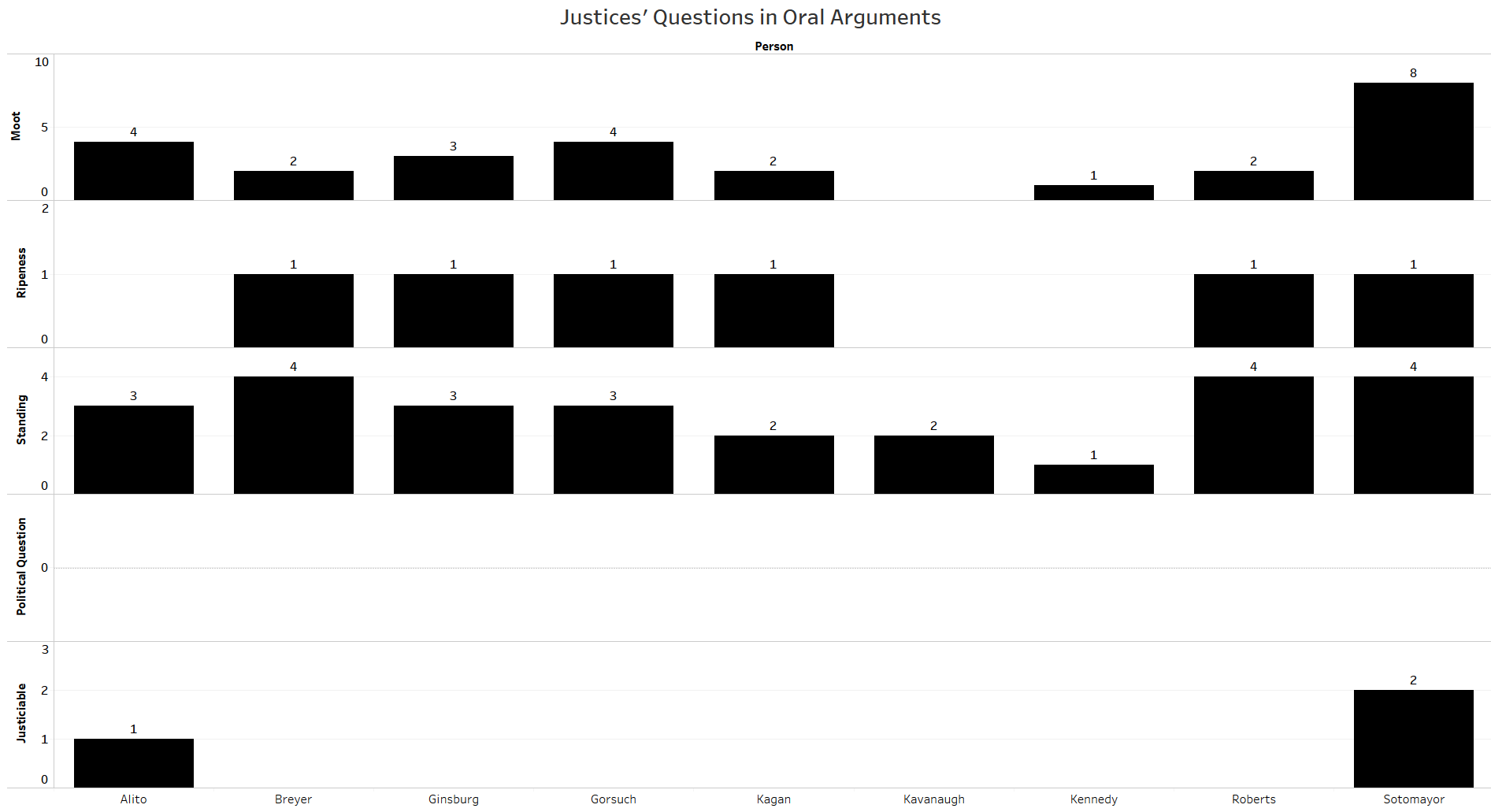

The next figure breaks the justices down by the number of oral arguments in which they mentioned at least one of these justiciability concerns.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor was the only justice to raise at least four of these doctrines in oral argument since the 2017 term. She also raised these doctrines the most times cumulatively, in 15 oral arguments for this period. Justice Neil Gorsuch brought up these terms the next most frequently at eight times, followed by Justice Samuel Alito at seven. Justice Brett Kavanaugh and his predecessor on the court, Justice Anthony Kennedy, raised these doctrines the fewest times, at two apiece.

Opinions

When we look at the court’s opinions, though, we see a very different trend for the justices.

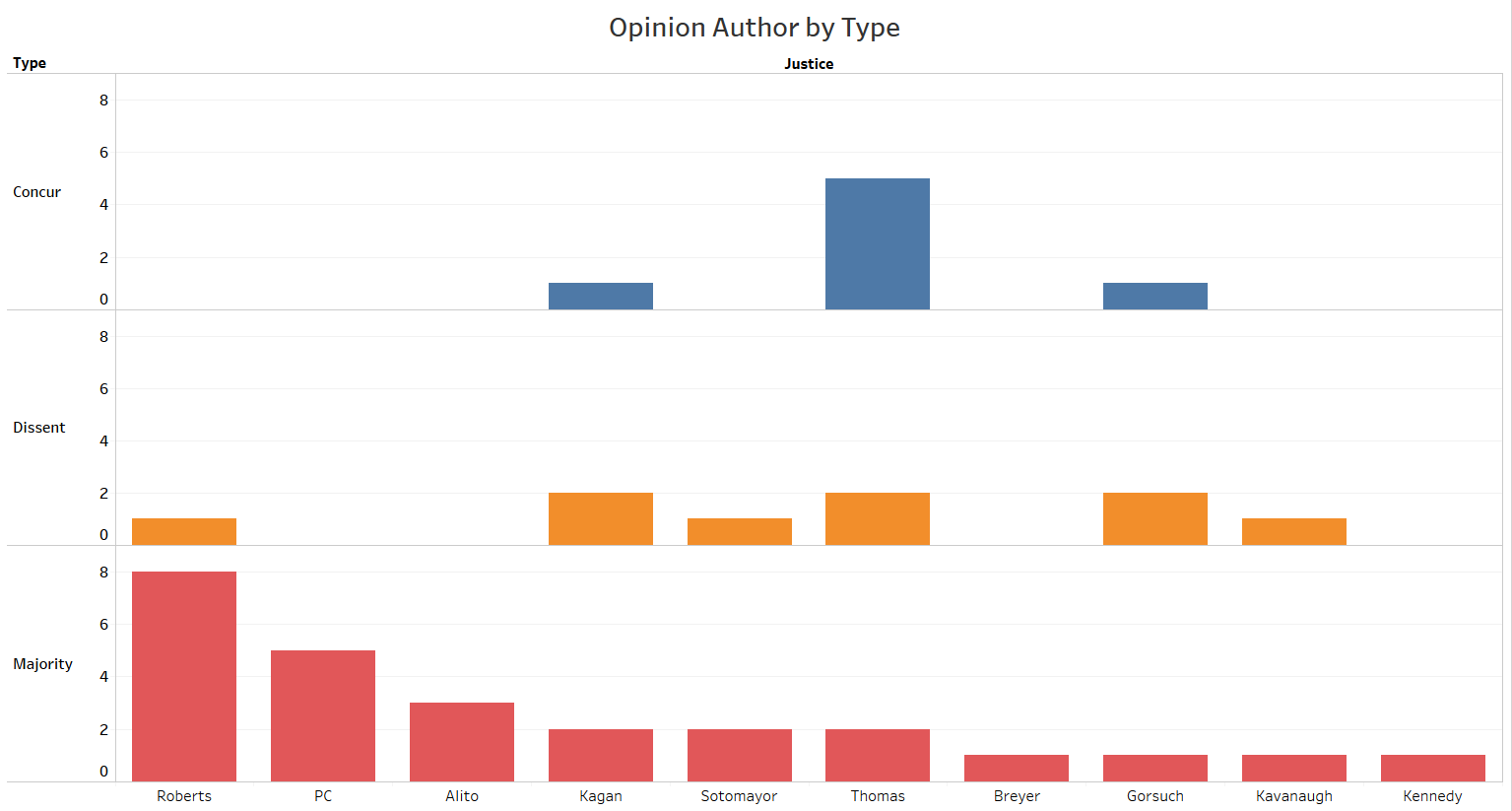

Roberts raised issues of justiciability far more often than any other justice in majority opinions, with eight such opinions. This is followed by five per curiam (unsigned) opinions and then by Alito, who authored three majority opinions referencing these issues or concerns. Roberts and Justice Clarence Thomas each authored nine opinions referencing justiciability doctrines, yet the breakdown of these opinions was quite different. Roberts wrote eight majority opinions and one dissent, while Thomas wrote only two majority opinions, along with two dissents and five concurrences.

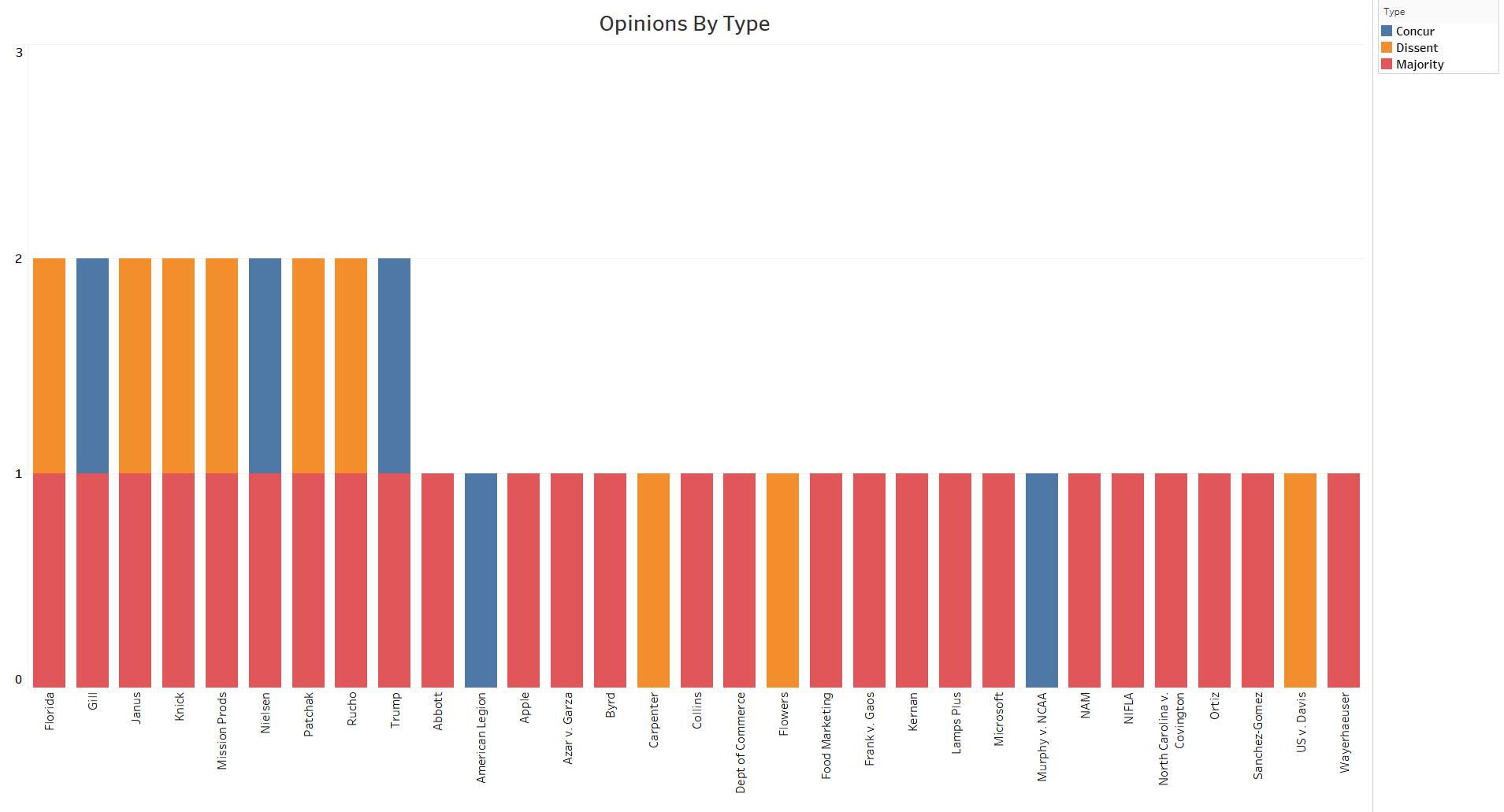

References to justiciability doctrines mostly arise in majority opinions and appear less frequently in the justices’ separate opinions. The following figure counts the number of opinions in which at least one of these doctrines was discussed (not the number of times these doctrines were mentioned within each opinion).

The doctrines were brought up in two opinions in the same case nine times. Each of these instances included a majority and one separate opinion. They came up in only one opinion in 22 decisions. These include 18 majority opinions, two dissents and two concurrences. In total, justiciability principles were mentioned in 27 majority opinions, five concurrences and eight dissents.

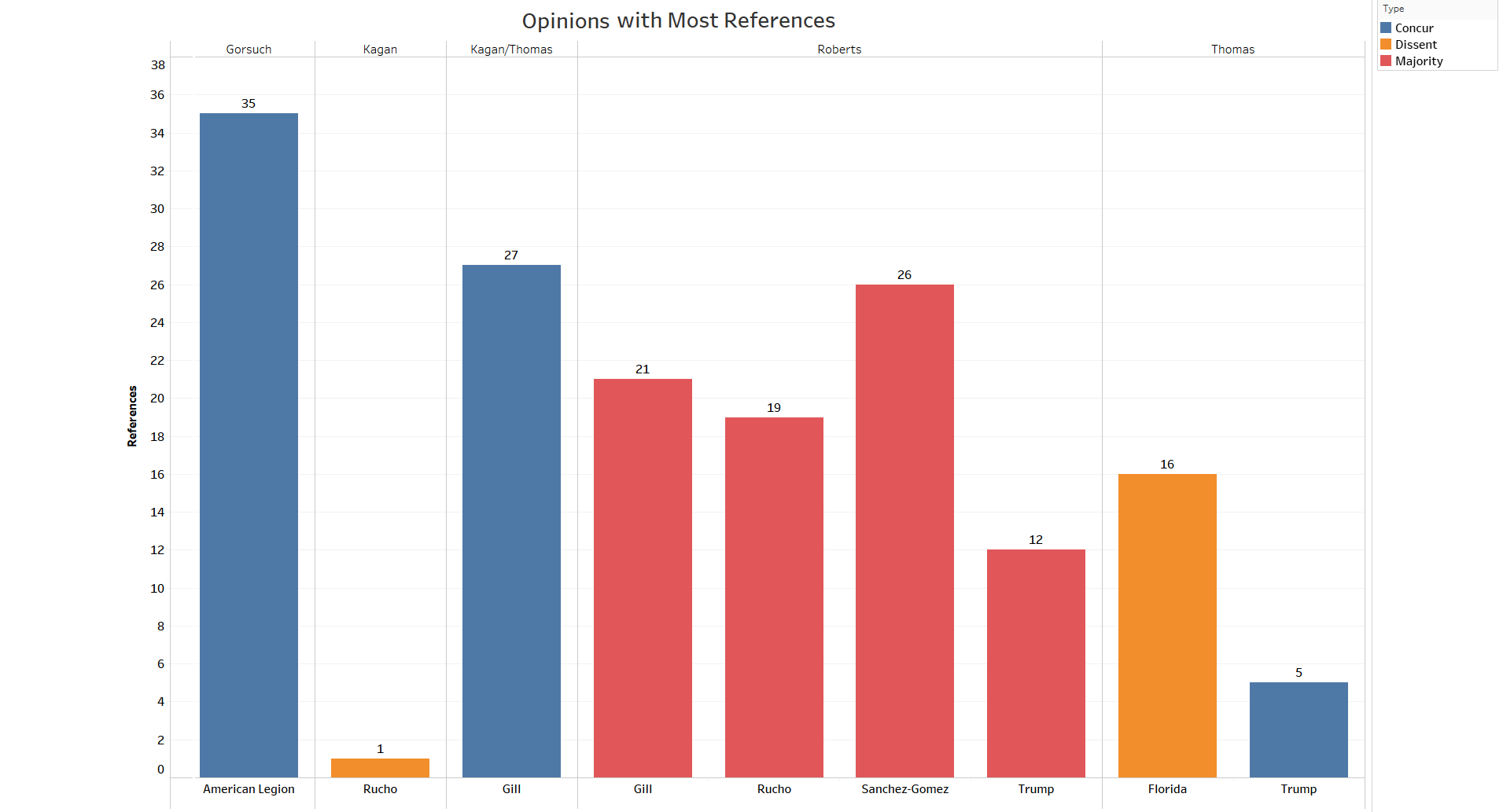

How often these terms came up within each of these opinions differed greatly. There were detailed discussions of these doctrines in a small set of cases. The six decisions that discussed these terms the most are covered in the following figure. [Please note that the six cases in this figure are based on total references across the decision including both majority and separate opinions, even though there are more than six columns because the figure is further broken down by opinion type and author.]

Gorsuch’s concurrence in American Legion v. American Humanist Association, which mainly hinged on standing, referenced at least one of these terms the most times, with 35 references. This is followed by Roberts’ opinion in Sanchez Gomez, with 26. (Justice Elena Kagan’s and Thomas’ concurrences in Gill v. Whitford together referenced these doctrines 27 times.)

Roberts occupies a unique space in this graph. He not only wrote more opinions in this figure than any other justice, with four, but he is also the only justice in this figure to write a majority opinion.

Roberts plays a unique role in helping direct the court to decide certain cases and avoid ruling in others. Even though he does not discuss these principles noticeably more frequently than the other justices in oral argument, he is clearly the most apt to discuss these concerns in majority opinions, both in terms of total opinions in which these doctrines arise and in terms of majority opinions in which they are discussed the most. Roberts has carved out this role for himself, exemplified by his majority opinion in Rucho. In this role he sometimes cautions restraint, while other times he appears more willing to render a decision even if a justiciability concern was brought to the court’s attention. This decision-making style may be related to Roberts’ role as chief justice, his concern for the Supreme Court as an institution or his own strategic preferences. Whatever the impetus though, Roberts’ involvement in this array of cases clearly sets him apart from the rest of the justices.

This post was originally published at Empirical SCOTUS.

Posted in Empirical SCOTUS