Argument analysis: Justices debate impact of “do-over” in capital case

Yesterday the Supreme Court heard oral argument in the case of James McKinney, who was sentenced to death for two murders in 1991. After the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit threw out McKinney’s death sentence four years ago, the Arizona Supreme Court reinstated it. The state court first rejected McKinney’s argument that a jury, rather than a judge, should resentence him. It then concluded that the mitigating evidence – that is, the evidence why McKinney should not receive the death penalty – was not “sufficiently substantial” to warrant a lesser sentence. Although it wasn’t entirely clear, after an hour of debate yesterday morning, McKinney appeared to face an uphill battle in convincing the justices to overturn the Arizona Supreme Court’s most recent ruling.

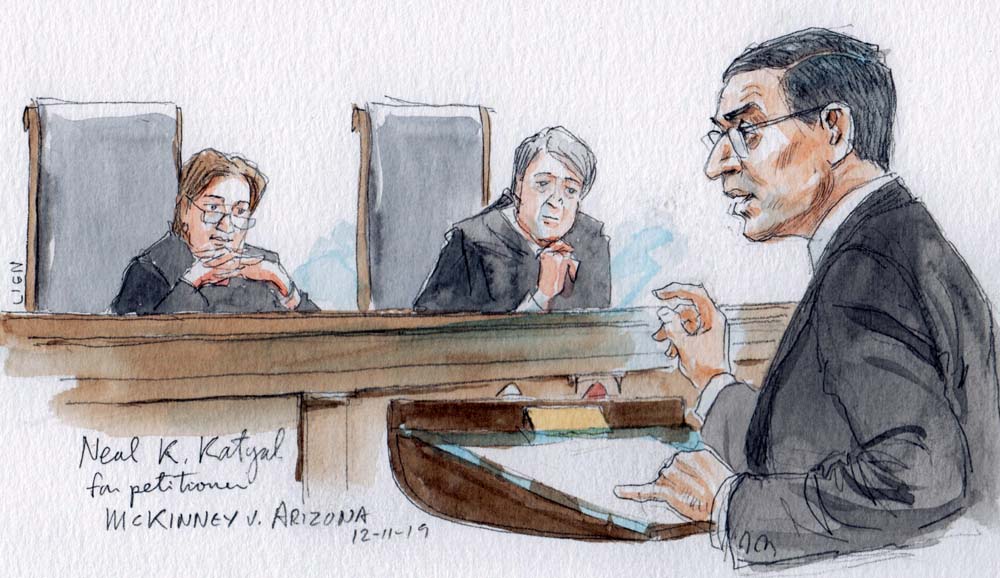

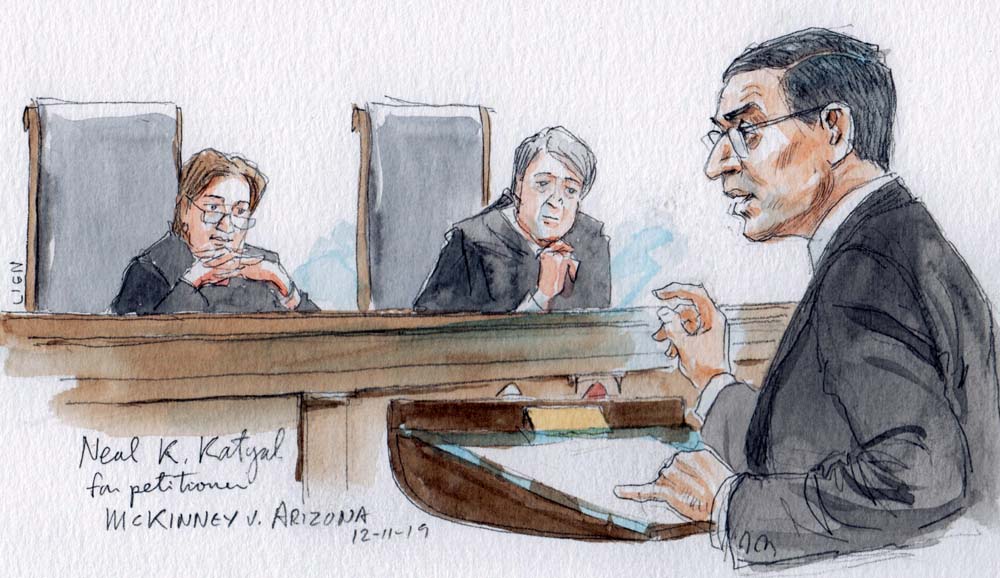

Arguing for McKinney, former acting U.S. solicitor general Neal Katyal urged the justices not to allow Arizona to execute McKinney, who had never had a sentencing proceeding that complied with current law. McKinney, Katyal explained, had two separate paths to victory. First, if McKinney were sentenced today, Katyal contended, there is “no doubt” that he would be entitled to a jury sentencing under the Supreme Court’s current caselaw. Or, Katyal continued, the Supreme Court could simply send the case back to the trial court for resentencing – a disposition that “breaks no new ground.”

But justices of all ideological stripes were skeptical. Justice Stephen Breyer asked why McKinney’s case needed to go back to the state trial court after the 9th Circuit’s decision. In Arizona, Breyer observed, the appeals court is intended to be the sentencer.

Justice Elena Kagan chimed in, asking Katyal why the Supreme Court’s precedents requiring a jury trial would apply. Wouldn’t McKinney be getting a “windfall,” she suggested, when the error in the earlier proceedings had nothing to do with the right to a jury sentencing?

Justice Brett Kavanaugh had a related concern. “You are requiring a new jury sentencing 28 years after the murders,” he told Katyal, after the victims’ families have already been through one sentencing proceeding. Why would you do that?

Katyal stressed that McKinney wasn’t trying to get a windfall. The state is conducting a brand-new sentencing proceeding, which has to comply with current law. And an appeals court should not decide a life-or-death issue like this when it doesn’t have the defendant or witnesses before it.

Justice Samuel Alito was dubious. You, he told Katyal, are in fact asking for a “double windfall” – the retroactive application of the Supreme Court’s cases requiring a jury to sentence McKinney and then another shot at convincing the jury that McKinney should not get the death penalty. “You have an entirely formalist argument,” Alito said. Your “real beef” isn’t that McKinney was entitled to be sentenced by a jury, but that he got the death penalty at all.

Justice Neil Gorsuch turned to a slightly different question. Arizona has argued that McKinney’s case had already become final, and that the Arizona Supreme Court’s resentencing of McKinney after the 9th Circuit’s ruling did not reopen that proceeding. Instead, the state has contended, the resentencing was simply a “collateral” proceeding. Normally, Gorsuch told Katyal, states get to define when their proceedings are final. What federal law, Gorsuch asked, do we apply to determine whether the state proceeding violates the Constitution? I “would have thought it would be a pretty deferential standard of review,” Gorsuch concluded.

Chief Justice John Roberts followed up on Gorsuch’s question. Where, he asked Katyal, do you draw the line between what does or does not reopen a proceeding? Is there a difference between a “surgical mistake” and an “entirely comprehensive mistake that affects the whole proceeding?”

Arguing for the state, Arizona Solicitor General Oramel Skinner faced questions, mostly from the court’s more liberal justices, about why – despite the state’s representations to the contrary – the resentencing proceeding after the 9th Circuit’s ruling didn’t reopen McKinney’s case on direct review, so that he would be entitled to have a jury resentence him. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg asked Skinner how, if the Arizona Supreme Court had made a mistake in the original proceeding, that mistake could be fixed without a “do-over”? There’s nothing “collateral” about it, Ginsburg said.

Kagan added that the federal courts, when reviewing an inmate’s claim for post-conviction relief, can only look at what happened in the inmate’s direct appeal; they don’t have any authority over state post-conviction proceedings. “Whatever you call it,” Kagan told Skinner, “you are redoing” the sentencing.

Kagan repeated this idea a few minutes later. Perhaps, she said, the label that a state gives to the proceeding doesn’t really matter when the state supreme court is redoing what it did on direct appeal. If you are just correcting an error, she suggested, calling it “collateral” doesn’t seem to make much of a difference.

In his rebuttal, Katyal warned the justices that a ruling for the state would allow states to “slap the label of collateral review” on all new proceedings in a case, allowing them to evade all kinds of constitutional requirements. But it wasn’t clear whether he had convinced at least five justices that a ruling for the state would be as problematic as Katyal described it.

A decision in the case is expected by late June.

This post was originally published at Howe on the Court.

Posted in Merits Cases

Cases: McKinney v. Arizona