Empirical SCOTUS: The recent role of separate opinions

on Nov 13, 2019 at 9:58 am

In a 2015 article for The Washington Post reviewing Melvin Urofsky’s book, “Dissent and the Supreme Court,” David Cole wrote, “What determines a great dissent … is not necessarily the power of the argument but the shifting tides of history. … History, not rhetoric or cogency, determines whether a dissent wins out in the long run. Yet by articulating a compelling alternative legal vision, a persuasive dissent can contribute to the arc of historical change.” Not only dissents, but all separate Supreme Court opinions have the potential to become law in later iterations of the court’s business.

Yet not all Supreme Court scholars view separate opinions positively. In a recent article, Professor Suzanna Sherry proposed not only eliminating dissents and separate opinions altogether, but also ending the practice of justices’ signing their names to opinions in order to do away with, or at least minimize, the celebrity status bestowed upon Supreme Court justices. In the space between praise for and criticism of separate-opinion writing, this analysis looks at how majority opinions have utilized separate opinions to generate and refine arguments that have directed the trajectory of the law over the past few terms.

Often separate opinions from previous decisions give justices templates for rectifying previous errors (from the justices’ perspectives) or updating the law to conform to current circumstances. The justices’ choices of which previous separate opinions to cite in majority opinions follow several well-worn paths. Certain justices tend to cite particular other justices. Certain cases tend to accrue greater numbers of cites from previous separate opinions. Particular justices more regularly cite prior separate opinions than other justices, and certain justices’ prior separate opinions are cited more often in the aggregate. The analysis in this post looks at majority opinions from the 2016 through 2018 terms that cite separate opinions from prior decisions (specifically, not separate opinions from the same cases as the majority opinions).

Separate opinion utility

Looking back at some of the most impactful dissents as measured using Cole’s criteria, Justice John Paul Stevens’ dissent from Bowers v. Hardwick presaged Justice Anthony Kennedy’s majority opinion in Lawrence v. Texas:

The rationale of Bowers does not withstand careful analysis. In his dissenting opinion in Bowers Justice Stevens came to these conclusions:

“Our prior cases make two propositions abundantly clear. First, the fact that the governing majority in a State has traditionally viewed a particular practice as immoral is not a sufficient reason for upholding a law prohibiting the practice; neither history nor tradition could save a law prohibiting miscegenation from constitutional attack. Second, individual decisions by married persons, concerning the intimacies of their physical relationship, even when not intended to produce offspring, are a form of ‘liberty’ protected by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Moreover, this protection extends to intimate choices by unmarried as well as married persons.” …

Justice Stevens’ analysis, in our view, should have been controlling in Bowers and should control here.

Pointing to prior dissents when overturning majority opinions from those very cases is not uncommon. Justice Clarence Thomas employed a similar tactic with his majority opinion in last term’s Franchise Tax Board v. Hyatt, which overturned the court’s decision in Nevada v. Hall. Several times in his opinion, Thomas pointed to dissents in Hall. He looked to then-Justice William Rehnquist’s dissent in stating, “Hall’s determination that the Constitution does not contemplate sovereign immunity for each State in a sister State’s courts misreads the historical record and misapprehends the ‘implicit ordering of relationships within the federal system necessary to make the Constitution a workable governing charter and to give each provision within that document the full effect intended by the Framers.’ (Rehnquist, J., dissenting).” Thomas cited Justice Harry Blackmun’s dissent to argue that “[t]he Constitution implicitly strips States of any power they once had to refuse each other sovereign immunity, just as it denies them the power to resolve border disputes by political means. Interstate immunity, in other words, is ‘implied as an essential component of federalism.’ Hall, 440 U. S., at 430–431 (Blackmun, J., dissenting).”

Separate opinions not only have supported propositions in majority opinions overturning prior decisions but also have led to legislative adjustments when Congress disagreed with Supreme Court decisions. One example was the passage of the Lily Ledbetter Fair Pay Act in reaction to the Supreme Court’s decision in Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. Ledbetter was an employment-discrimination case in which the female plaintiff alleged that she was paid less than similarly situated male employees. Under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, employers cannot be sued for race or gender pay-discrimination if the claims are based on decisions made by the employer more than 180 days earlier. The court ruled 5-4 that Ledbetter had not brought her claim within the required 180-day window, rejecting her argument that each paycheck received constituted a separate discriminatory act. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s dissent in the case emphasized that the majority’s rule unfairly required pay-discrimination plaintiffs to file suit before they could realistically determine that any discriminatory pay practices existed.

When Congress debated the Ledbetter Fair Pay Act, several legislators pointed to Ginsburg’s dissent in the case:

- Congressman Steny Hoyer: “In fact, every paycheck that Lilly Ledbetter received after Goodyear’s decision to pay her less was a continuing manifestation of Goodyear’s illegal discrimination. As Justice Ginsburg said in dissent, each subsequent paycheck was ‘infected’ by the original decision to unlawfully discriminate.”

- Congressman John Conyers: “By passing this legislation here today, Congress will be heeding Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s call to stand up and ensure that no American’s income should be determined by race, sex, creed, color, or sexuality.”

- Congresswoman Nancy Boyda: “Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was one of the four Supreme Court justices who disagreed with the ruling, and she called upon Congress to act. H.R. 2831, the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act is Congress’s response. … While I respect the Supreme Court, I believe that Justice Ginsburg was correct when she stated that the Court’s decision ignored real-world employment practices. This is not a gender issue; all employees should have an equal chance of getting a just wage.”

- Congresswoman Betty McCollum: “In this decision, the Court ruled that Lilly Ledbetter, a former supervisor at a tire plant in Alabama, was not eligible to receive back pay for pay discrimination because she had not filed her claim within 180 days after the first ‘unlawful employment practice occurred.’ However, as Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg highlighted in her dissent, pay discrimination occurs over time in small increments and is frequently not discovered for many years. It is more than disappointing that this decision increases the barriers to fair compensation for victims of pay discrimination.”

On January 27, 2007, the House of Representatives passed the Ledbetter Fair Pay Act by a 250–177 margin.

Statistics

Several practices are apparent when looking at Supreme Court justices’ citations to separate opinions from previous cases. These cites tend to cluster in specific cases and, not surprisingly, often relate to when the court overturns its past decisions.

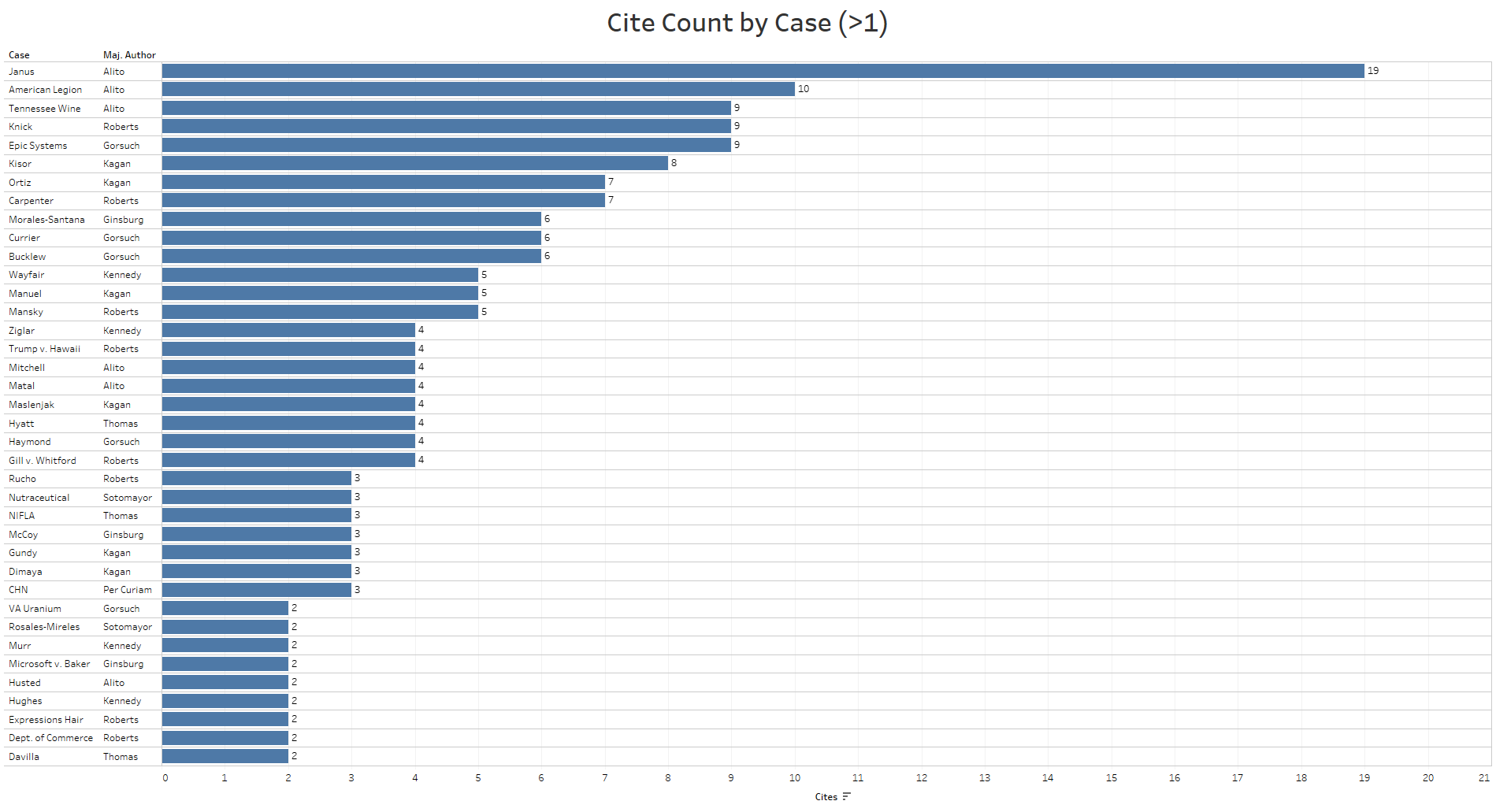

Three of the cases with the most cites in the majority opinion to previous separate opinions — Janus v. AFSCME, Knick v. Township of Scott and South Dakota v. Wayfair — all involved overturning past precedent. The court also considered overturning past decisions in two of the other cases with high separate opinion-citation numbers, American Legion v. American Humanist Association and Kisor v. Wilkie. This trend is consistent with the qualitative evidence educed above.

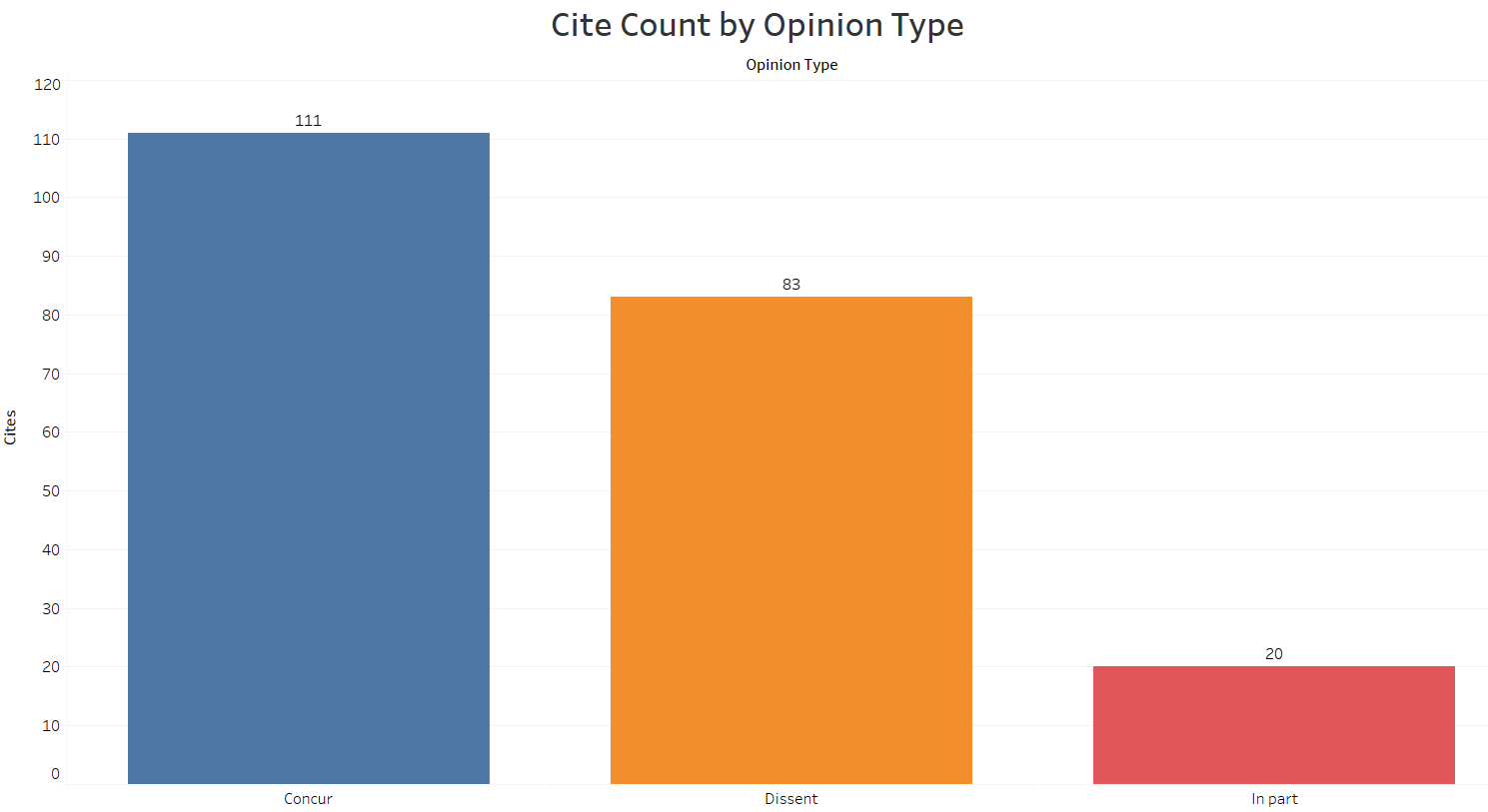

Interestingly though, the bulk of citations to separate opinions from the past three terms did not come from prior dissents.

In fact, cites to concurrences outnumbered cites to dissents 111 to 83. Twenty of the citations were to mixed concurrences and dissents.

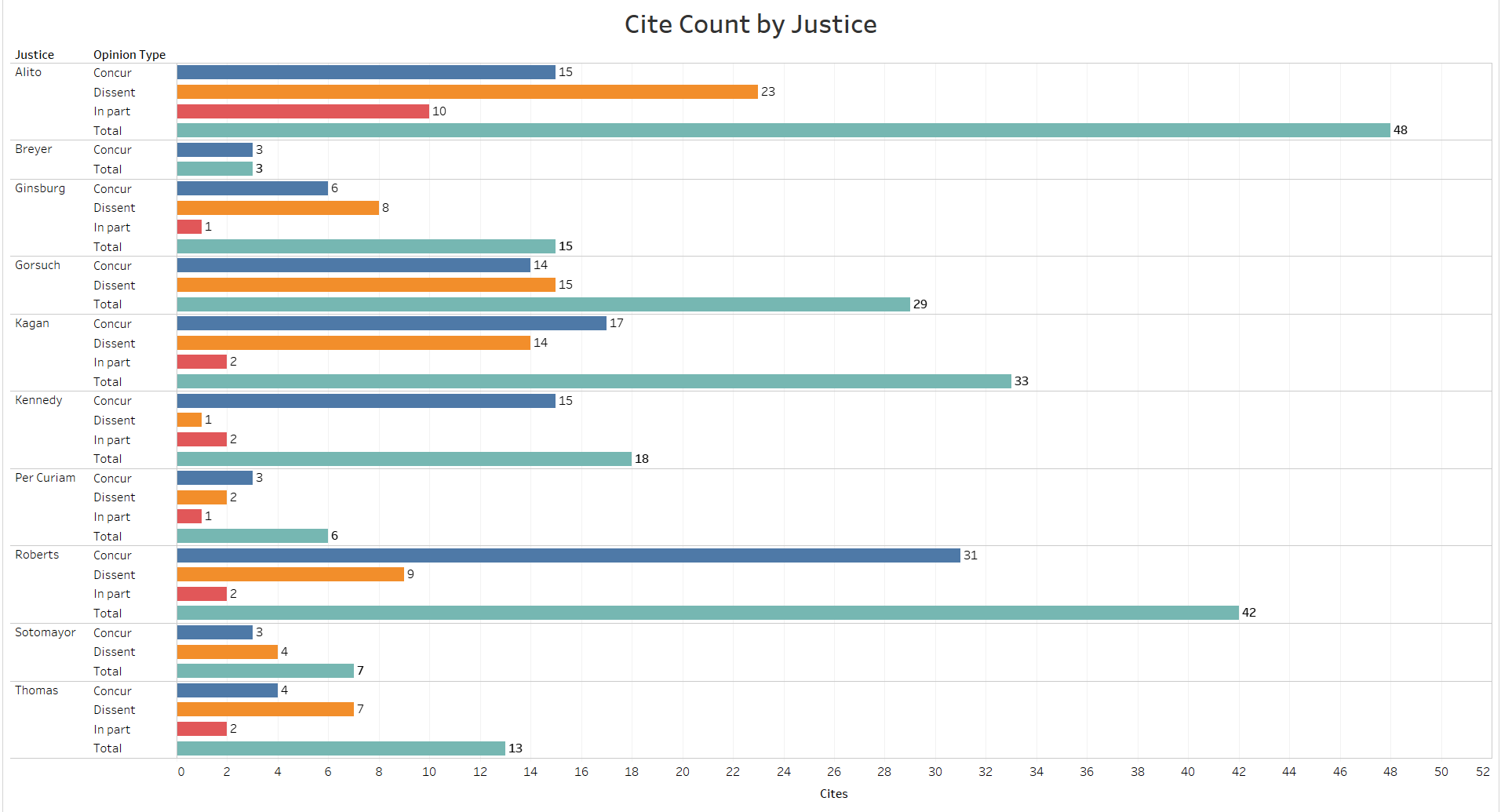

Of the current justices, Justice Samuel Alito cited the most separate opinions in his majority opinions during this period.

Alito’s cite count runs so high in part due to the fact that he authored the three majority opinions with the most citations to prior separate opinions: Janus, American Legion and Tennessee Wine and Spirits Retailers Association v. Thomas (which is one of several majority opinions that contain nine cites to prior separate opinions). Alito not only cited the most dissenting opinions but also cited the most concurrences and dissents in part. Roberts cited the second most prior separate opinions with 42. His mix of citations is far more weighted toward concurrences, which constitute 31 of his 42 cites. Justice Stephen Breyer cited the fewest separate opinions with three; all came from concurrences.

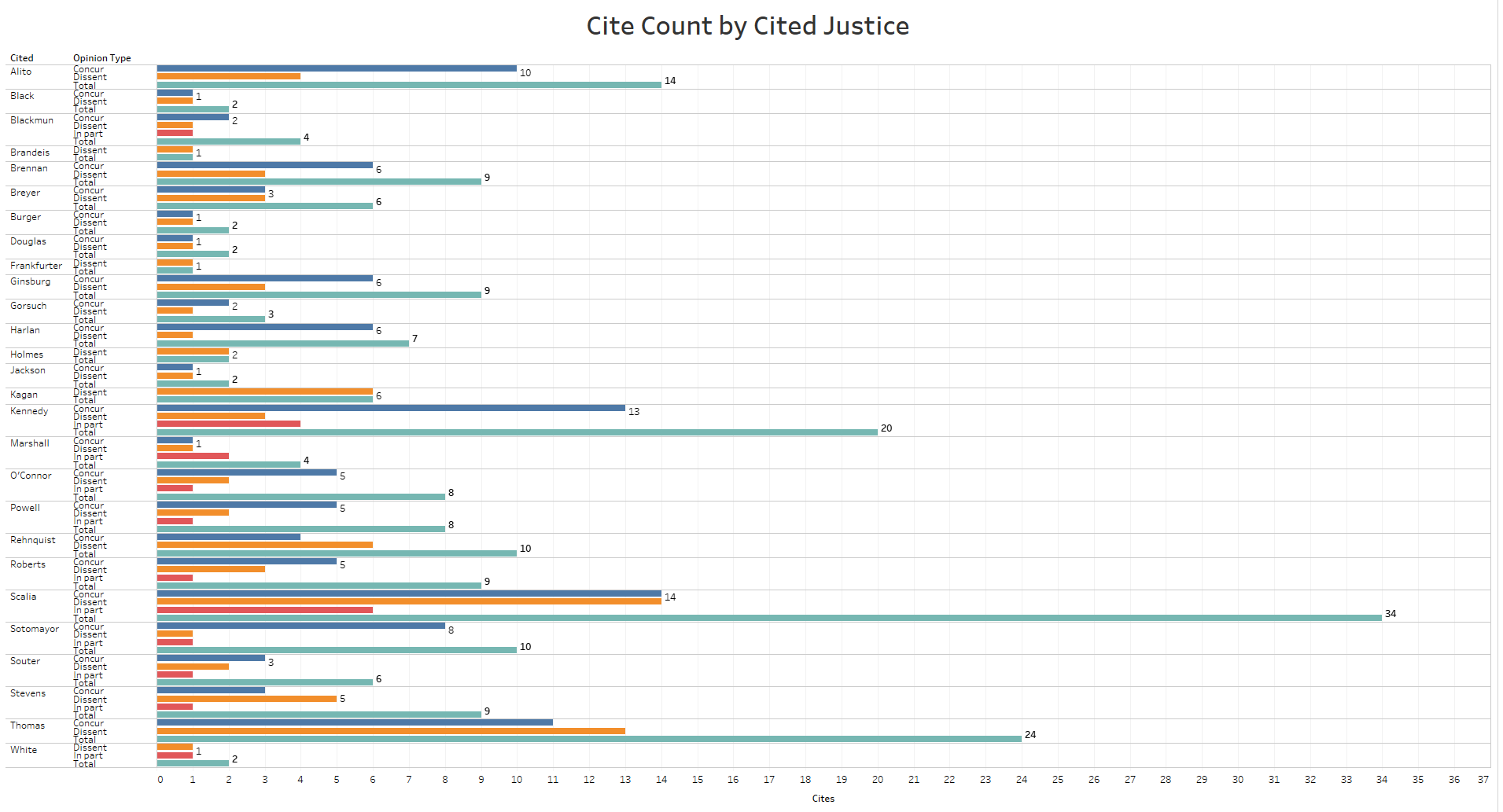

In what will probably not surprise many court-watchers, the justice whose prior separate opinions were cited most often was Justice Antonin Scalia, who had some of the most notable dissents over the past several decades.

What might surprise some, though, is that Scalia was cited equally for his dissents and concurrences. The second-most-cited justice, Thomas, was one of the most prolific dissenters of the past several terms. Thomas’ dissents were cited more often than his concurrences, but only by a ratio of 13 to 11. Kennedy and Alito were the third and fourth most-cited justices. Multiple retired justices were also cited frequently, including Rehnquist 10 times and Justice William Brennan nine.

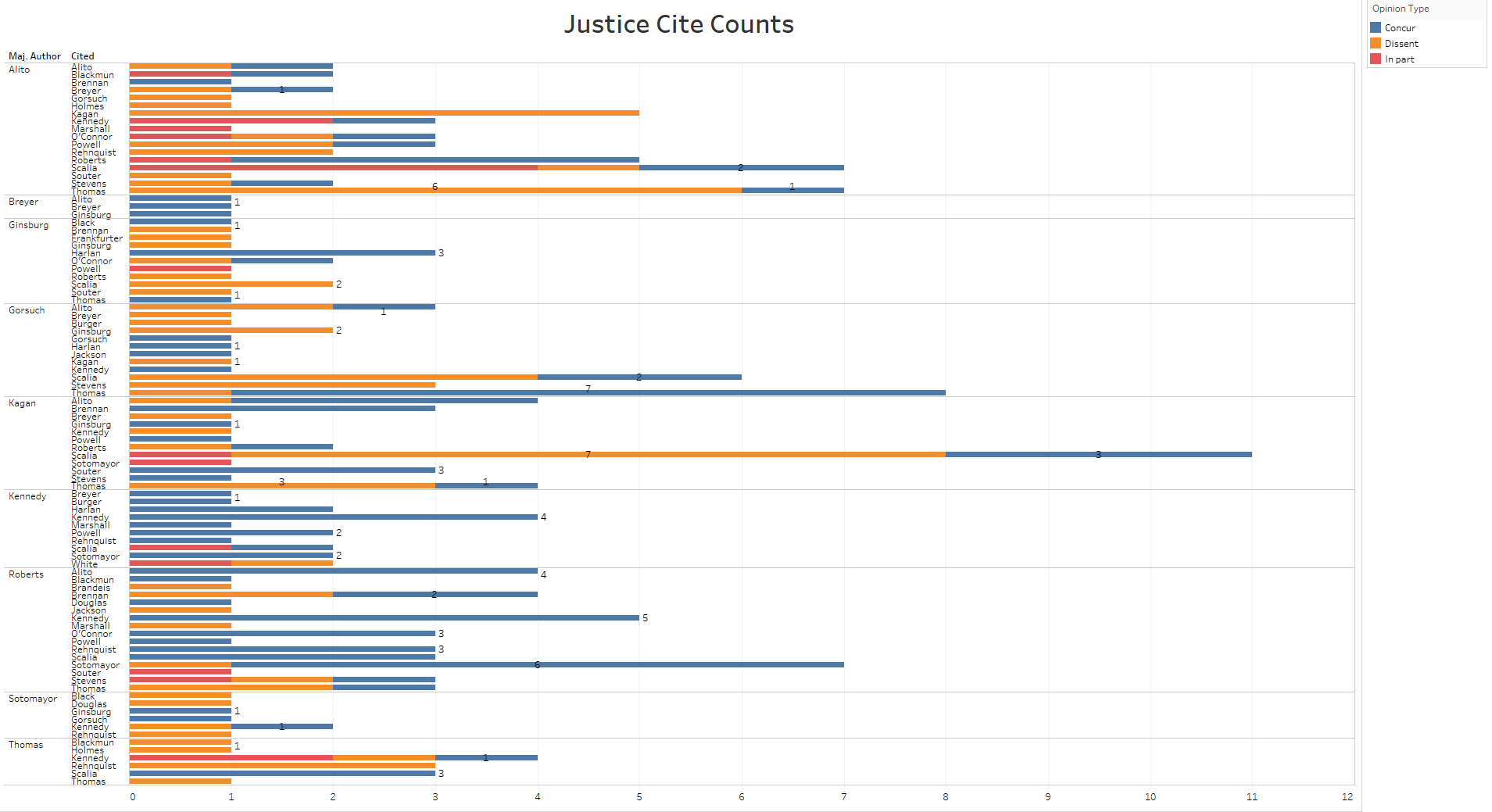

The justices also seem to have developed patterns in citing particular other justices’ opinions.

The greatest number of cites from any of these relationships is between Justice Elena Kagan and Scalia. Kagan cited Scalia’s opinions 11 times, including seven dissents, three concurrences and one concurrence and dissent in part. Kagan’s seven cites to Scalia’s dissents topped the count for one justice’s cites to another’s dissents, and was followed by Alito’s six cites to Thomas’ dissents. In terms of concurrences, Gorsuch cited Thomas seven times, the most among the justices, followed by Roberts’ six citations to Sotomayor’s concurrences. Gorsuch also had the second-most cites to a particular justice after Kagan’s cites to Scalia’s opinions, with his eight cites to Thomas’ separate opinions.

The justices are clearly strategic in their use of separate-opinion cites within their majority opinions. This gives the justices a chance to develop the judicial record in a manner that conveys compelling ideas that did not initially form the basis of law. Cites to secondary opinions give these cogent analyses new life by incorporating them within the court’s majority opinions, occasionally pointing out flaws in previous majority opinions. The justices utilize this practice in varying degrees, but as a general matter, they appear to look to past separate opinions frequently, both to rehash old ideas and to help justify new ones.