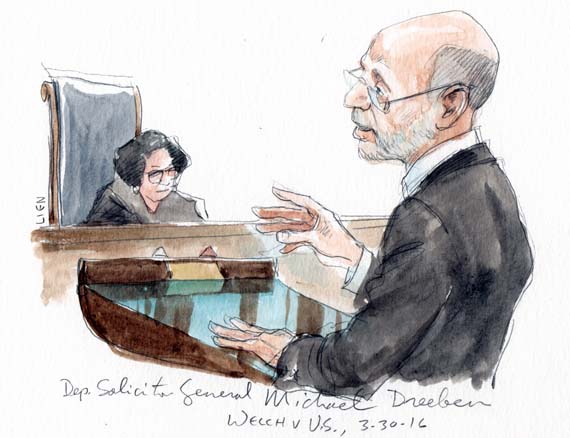

Learning about error from Michael Dreeben

on Aug 1, 2019 at 3:30 pm

Neal Katyal is a partner at Hogan Lovells, and Paul and Patricia Saunders Professor of National Security Law at Georgetown University Law Center. He served as Acting Solicitor General of the United States from May 2010 until June 2011.

Michael Dreeben, an advocate who basically never makes an error, is the one who taught me all about them. For decades, his work has embodied the heart and soul of what the Office of the Solicitor General has historically always been about: brilliant advocacy tempered by a commitment to doing justice.

I first saw Michael argue when I was clerking for Justice Breyer. The case was United States v. O’Hagan, an important securities-fraud case. Several of the clerks had spent months studying the case, and I personally didn’t see any way for the government to prevail. Then Michael stood at the podium. I had never seen anything close to that tour-de-force. I remember within a few seconds of the argument starting, Justice Scalia was all over him about the line between legal and illegal. In a few short words, Michael disarmed the question and provided a clean, relatively easy-to-administer test. And it did not stop there. He jumped on every question, parrying them back as if it were a conversation at the dinner table. He deftly explained the limits of his position and why many of us were seeing the case the wrong way. In an opinion authored by Justice Ginsburg, six justices agreed with him.

So it took no thought at all for me, when I had my first Supreme Court argument, to know who I wanted to watch — Michael. My case was a difficult one, involving Guantanamo (Hamdan v. Rumsfeld). And I went to watch him argue every one of his cases. I copied down words he used, transitions he made, even the way he stood at the podium. It turned out that I was not able to emulate any of it.

Three years later, I found myself on the other side of the courtroom, joining the SG’s office first as principal deputy solicitor general and then acting solicitor general. Every morning that I knew a brief for which Michael was the deputy was coming in for review, I breathed easier. I knew it would be meticulous, having gone through innumerable drafts with the assistant. Everything would be well thought out, counterarguments raised and answered. And that was all great, but I want to spend my few remaining words on the most important thing Michael taught me.

As lawyers, we are supposed to zealously advocate for our clients. In the SG’s office, that client is the United States, which one would think translates into those attorneys’ siding with the prosecution. After all, cases are called United States v. O’Hagan (or Smith, or whomever). But there is an important quirk that goes all the way back to at least Solicitor General William Howard Taft: confessions of error. That occurs when the solicitor general tells the court, “You know that case we won below. We shouldn’t have won it. Please agree to hear this case and reverse the decision and rule against the United States.”

Wow. That practice defines what it means to be a government lawyer – your client is not the prosecutors, but rather the American people. You actually argue against the position the United States took in the court below, saying a conviction should be reversed. It takes a special kind of person to be as dedicated to that precept as to winning cases for prosecutors, when so much of your work is about the latter.

Michael was that person. Indeed, when I wrote about the practice of confessions of error, it was Michael I had in my mind. He came into my office three or four times a year, telling me why we had to confess error in a particular case. His presentations were always infused with fairness and justice. To have this brilliant man, who had dedicated his life to the administration of the criminal law in our federal system, come in and explain why the United States should lose a case that it had already won could be tear-producing. And I learned more from him than I ever could about what it means to follow the inscription on the wall in the attorney general’s conference room: “The United States wins its point whenever justice is done its citizens in the courts.”