Empirical SCOTUS: The “right” stuff

on Aug 16, 2019 at 1:58 pm

The Constitution as originally drafted did not include certain specific rights and restrictions on the power of the government. These were instead later added as amendments to the Constitution in the form of the Bill of Rights. Commentary leading up to the establishment of the Constitution found in the Federalist Papers discusses the importance of amendments and the process by which they might be established. In Federalist No. 85, Alexander Hamilton describes the amendment process and opines on the relative ease and difficulty of passing amendments once the Constitution has been ratified. The purpose of the Bill of Rights is explained in its own preamble: “Conventions of a number of the States, having at the time of their adopting the Constitution, expressed a desire, in order to prevent misconstruction or abuse of its powers, that further declaratory and restrictive clauses should be added: And as extending the ground of public confidence in the Government, will best ensure the beneficent ends of its institution.”

These rights, along with others subsequently adopted by the nation through the constitutional amendment process, and their proper interpretation have become some of the most heavily litigated issues before the Supreme Court. Cases arising under certain amendments, especially the First and Fourth Amendments, often come up multiple times each term. This post looks at when issues relating to constitutional amendments have been raised in recent Supreme Court litigation by examining the questions presented in cert petitions in each case in the Supreme Court’s online archive (which goes back to 2007). To locate the cases examining questions relating to each amendment, I searched within the Supreme Court’s questions presented for the term “amendment” and retrieved information related to any case in which the QP looked at a constitutional amendment. This covers 153 QPs in cases through those granted for the upcoming 2019 Supreme Court term (There were 186 hits in the search before consolidated cases and cases not dealing with constitutional amendments were removed.).

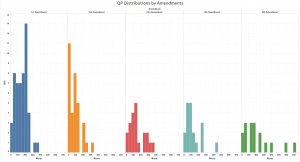

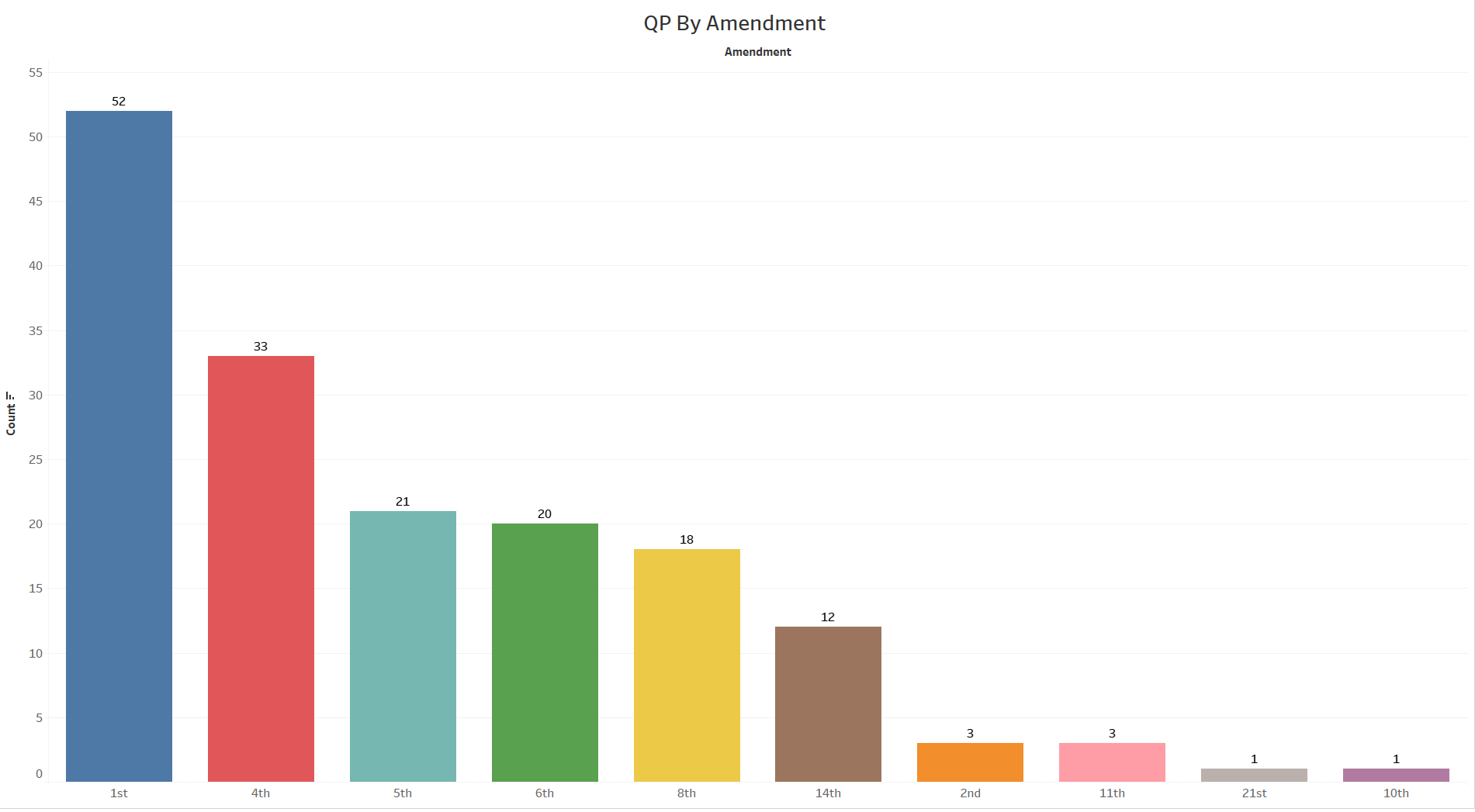

So how many cases does the court grant relating the various amendments? The first graph has a figure with overall QP counts by amendment. Multiple amendments were coded for a case when they appeared in the same QP. One exception has to do with cases dealing with the 14th Amendment. If the 14th Amendment was only discussed because of a right already incorporated to the states, then the 14th Amendment was not coded for a given case.

First Amendment cases were most prevalent and also surrounded a number of different issues. The majority of First Amendment cases were speech-related, but a number also dealt with voting rights, campaign finance, freedom of religion, retaliation claims and other issues. Fourth Amendment QPs were the second most frequent, and almost all of them looked at the reasonableness of police searches. Most Fifth Amendment QPs dealt with due process, Sixth Amendment QPs tended to deal with the right to counsel and to a jury trial, and Eighth Amendment QPs often examined standards for cruel and unusual punishment.

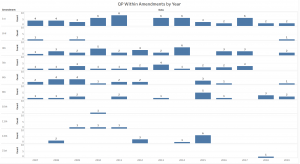

How were these QPs distributed across time? The next figure looks at the number of QPs that raised an issue under a given amendment based on the year of the cert grant.

A few points to note about this figure. First, not all cases that implicate an amendment raise it in the QP, and so these numbers likely undercount the total number of cases in which these types of questions arise. Second, Supreme Court terms and cert-grant years do not always line up. For instance, there were no First Amendment QPs in the 2012 batch of grants – even though the court heard AID v. Alliance for Open Society International during the 2012 term, and the QP in this case raised a question under the First Amendment – because the cert grant was in 2013.

Based on the large number of First Amendment QPs in general, it should come as no surprise that most terms had more First Amendment QPs than QPs dealing with other amendments. Fourth Amendment QPs were spread out across most terms as well though the year, with the most Fourth Amendment grants in 2014. The most Eighth Amendment grants in a year was five in 2015, while the court considered twice as many 14th Amendment QPs in 2015 as it did in any other calendar year since 2007. The 2019 term already has QPs looking at issues under the First, Second, Fourth, Fifth and Eighth Amendments.

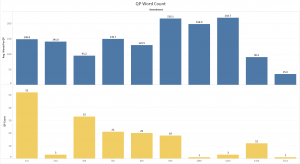

One other interesting aspect of these QPs is that some varied considerably in length depending on the amendments they examined (Length was measured by the QP word count taken from the entire length of the QP considered by the court.). Although it is difficult to make general claims about the length of QPs dealing with amendments that the court considers infrequently, such as the Second Amendment, amendments examined in a greater number of QPs give us a better sense of the typical length for such QPs. In the next figure, the top graph has the average QP word counts by amendment and the bottom graph has the count of QPs by amendment.

Many of the amendments have QPs of similar length. One noteworthy difference is Eighth Amendment QPs, which are quite a bit longer on average than those under other amendments with large numbers of observations. The word-count distributions that make up these averages help with understanding these differences. The following figure has the distributions for the First, Fourth, Fifth, Sixth and Eighth Amendments.

The differences in these distributions help to explain why Eighth Amendment QPs had a significantly larger mean. While most Fourth Amendment QPs were on the short side, at under 40 words, the largest bin of First Amendment QPs had just fewer than 200 words. Eighth Amendment QPs were spread out, but several were 400 words or more. The longest QP was for the Eighth Amendment case Madison v. Alabama, which had 691 words. On the other end of the spectrum, the court considered three QPs with 14 words each, including the QP for an Eighth Amendment case the court will hear next term: Kahler v. Kansas.

Focusing on the oral arguments in these cases for a moment, 32 attorneys argued in three or more of these cases. These attorneys with three or more oral arguments are shown below.

Michael Dreeben, one of the few attorneys with over 100 oral arguments before the Supreme Court and who recently retired from the Solicitor General’s office, argued the largest number of cases in this set, with 20. He is followed by former SGs Donald Verrilli with 16, Paul Clement with 10, and Neal Katyal with eight. Another prolific government attorney, Edwin Kneedler, is next with seven arguments. Three attorneys have six arguments apiece: Nicole Saharsky and Ian Gershengorn (also a former SG) both argued cases for the government, while Jeffrey Fisher has the most arguments for an attorney who did not argue cases for the federal government during the time period of this case set.

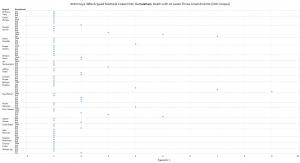

We can split these attorneys by several case characteristics. The next figure looks at attorneys with arguments in cases that cumulatively dealt with at least three different constitutional amendments. This list includes 16 attorneys.

Michael Dreeben and Donald Verrilli both argued cases with QPs that raised questions under six amendments altogether. Paul Clement, Neal Katyal, Ginger Anders and Carter Phillips each argued cases with QPs raising issues under five different amendments in total.

The next figure focuses on attorneys who argued multiple cases with QPs looking at the same amendments.

Michael Dreeben’s nine arguments in Fourth Amendment cases top the list, followed by Donald Verrilli’s seven arguments in cases with QPs looking at the First Amendment and Dreeben’s seven arguments in cases with QPs looking at the Sixth Amendment. After this, two attorneys argued cases with five QPs addressing the same amendments: Paul Clement with QPs looking at the First Amendment and Donald Verrilli with QPs looking at the 14th Amendment.

Even though many attorneys argued multiple cases in this set, over three times as many attorneys argued in only one case compared with those who argued in multiple cases. Based on the multiple arguments of attorneys from the SG’s office, many of these cases had dimensions of interest to the federal government. Many of these cases also involved issues relevant to state governments, as states or states’ officers were parties in more than a handful of these cases.

QPs provide a heuristic device to quickly understand the general issue of a case. They are extremely important, because they may be the first thing a clerk (or justice) looks at when reviewing a cert petition. Often, important aspects of cases are not captured in QPs, although when drafted well, a QP can signal important reasons why the court should grant cert in a case. One potentially salient reason for a cert grant is when government actions may run awry of rights protected by constitutional amendments. Many veteran attorneys are well versed in arguing these cases and continue to do so. The large number of attorneys arguing only one of these cases, though, shows that features aside from attorney experience are relevant, and that attorneys based in the geographic areas where these issues arise and who have specific expertise in these subjects may very well be the ones arguing before the justices in future cases.

This post was originally published at Empirical SCOTUS.