Empirical SCOTUS: A class of their own: The Supreme Court’s recent take on class actions

Supreme Court decisions tend to impact more than just the individuals named in a lawsuit. Supreme Court Rule 10, the one official written description of factors that may lead to a higher likelihood of a cert grant, focuses primarily on areas with inconsistent court decisions across the country. One of the rationales behind this theory is to assure that a Supreme Court decision affects people beyond the parties to the particular lawsuit in question. Another secondary means for the court to assure that its decisions affect a diverse population is by adjudicating cases starting as class actions (and the rules governing them). Class actions, by definition, involve more than just individual plaintiffs, and so clarifying correct class-action procedures can have an exponential outward effect. Although class actions are seldom discussed as a distinct area of Supreme Court adjudication, the court grants cert in multiple cases that started as class-action lawsuits each term. Between the 2010 and 2018 terms, the court decided between five and 10 cases per term that started as class actions (these cases were coded based on Supreme Court opinions describing the case origin as a class action).

The types of class-action lawsuits that eventually are heard by the Supreme Court arise in a multitude of subject areas ranging from consumer actions to criminal, employment and securities cases (Westlaw and the Supreme Court Database were both used to help classify subject area. Note that not all cases fell into a classifiable subject area, and so some of the analyses below contain fewer than the total number of observations.) In each of these areas, multiple individuals are affected by the same underlying actions.

There are predictable aspects to Supreme Court review in these cases. Many class actions that the court reviews, for instance, are heard below by a narrow range of lower courts.

Since 2010, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit heard over four times as many of these cases before Supreme Court review than any other appeals-court circuit. At the trial-court level, the District Court for the Central District of California (part of the 9th Circuit) heard twice as many of these cases as the next most prolific trial court, the District Court for the Northern District of California (also part of the 9th Circuit). The next set of trial courts with three class actions apiece includes another federal district court from California – the District Court for the Southern District of California.

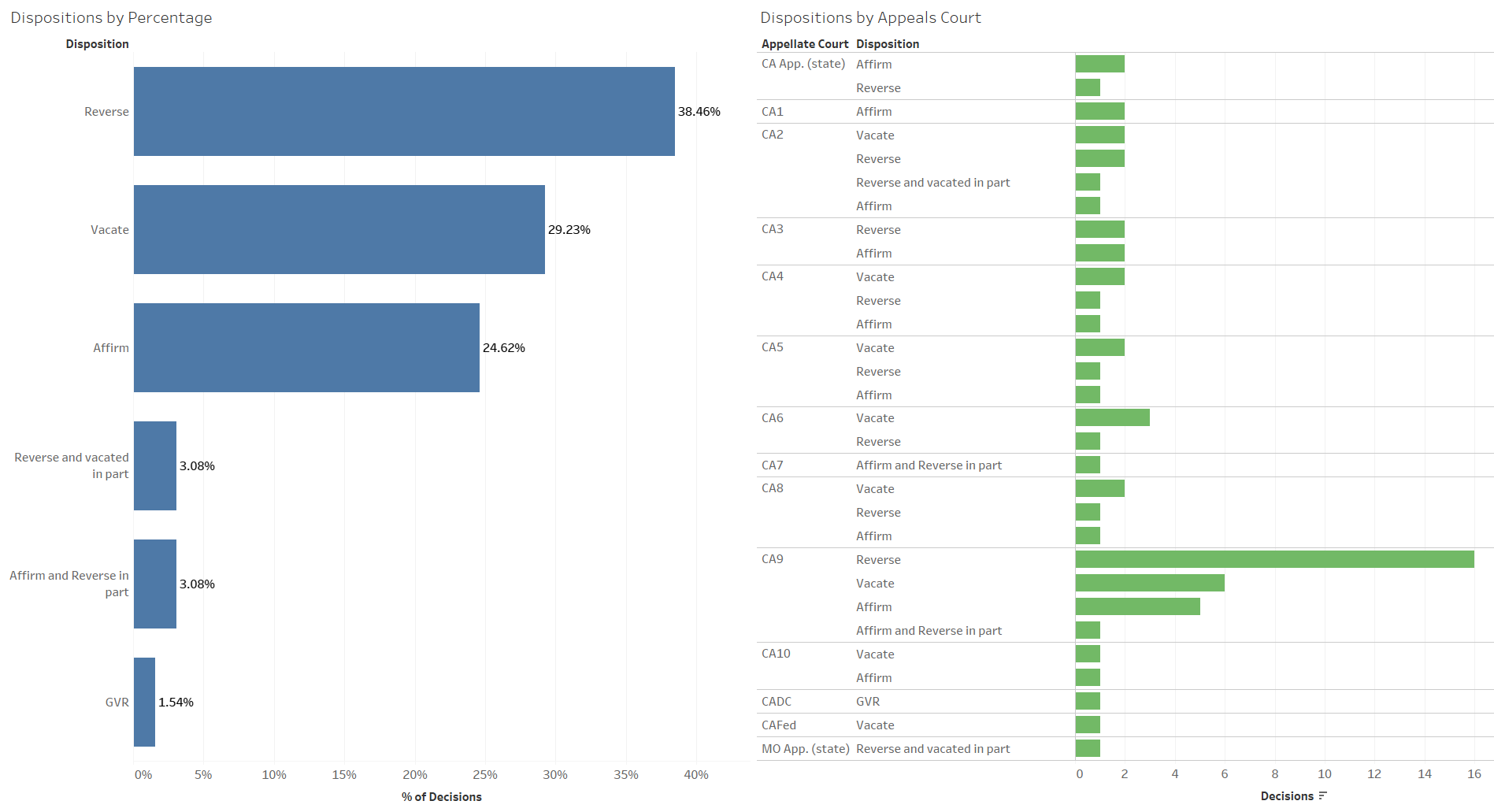

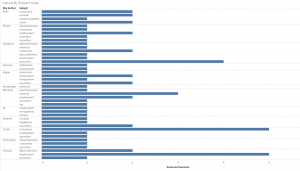

The Supreme Court overturns almost 70 percent of class action decisions made by appeals courts by either reversing or vacating these decisions. The graphs below look at the court’s dispositions in these cases in the aggregate as well as by individual courts of appeals.

The Supreme Court, for instance, reversed or vacated 22 class actions decided by the 9th Circuit while only affirming five. Although the court did not adjudicate nearly as many class actions from any other appeals circuit, the court did overturn the majority of class-action decisions heard by several other circuits as well. The court, for example, only vacated or reversed decisions from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit and vacated the one class action it decided after adjudication by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit.

Looking at the Supreme Court’s decisions in these cases based upon the lower court is only one way to slice these cases. Along with the various subject areas of these class actions, we can also look at the outcomes in these cases and the parties the court ruled for in its decisions.

Although many of the outcomes across subject areas only garnered a decision or two, some of the outcomes and differentials in outcomes are more pronounced. The differentials are also often notable within particular subject areas. For example, the court between the 2010 and 2018 terms favored the defendant companies in the vast majority of consumer class actions. The court was much more balanced in securities class actions between ruling for investors and the corporate entities in question. One of the common outcomes across the board was for the court to vacate the decision below and clarify the law for the appeals court. Many of these decisions did not favor either party but left room for the court below to rule on the cases’ merits based on such legal clarification. We see this propensity to clarify the law most frequently in employment class actions, but we also see in such cases that the court ruled in favor of companies more often than in favor of employees.

The justices have taken different roles in deciding cases beginning as class actions, with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg the clear leader.

With 19 opinions (10 majority opinions and nine dissents), Ginsburg authored four more opinions in total than Justice Stephen Breyer, who came in second. Justice Anthony Kennedy had a high ratio of majority to dissenting opinions, with eight majority opinions to only one dissent. Chief Justice John Roberts had a slimmer ratio than Kennedy, at four majority opinions to one dissent. Justice Sonia Sotomayor was the only justice to write more dissents than majority opinions in these cases, with four dissents to three majority opinions.

The justices specialized in different types of resolutions for these cases. When case resolutions were broken into five types — clarifying class action procedures, ruling on jurisdiction, justiciability (whether the Supreme Court should hear the case at all), or deciding based on precedent or through statutory interpretation — the justices each had particular focuses.

Ginsburg was the leading justice for clarifying class-action procedures, with four such decisions. A bevy of justices decided one case apiece based on jurisdiction or justiciability factors. Justice Antonin Scalia decided the most cases based on precedent, while Justice Clarence Thomas was the leading justice deciding cases through statutory interpretation (note that not every case neatly fell into one of these categories).

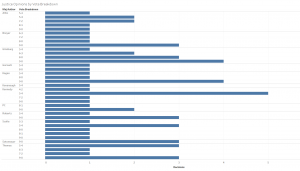

The justices specialized in different class-action subject matter, as is evident in the graph below.

Four justices in particular dominated decisions in certain areas of law. The bulk of Thomas’ decisions were in the employment class-action arena, where he decided more cases than any of the other justices. Similarly, Scalia decided the most consumer class actions, with five. Ginsburg decided more securities class actions than any other type, with four. Finally, Kennedy wrote majority opinions in more criminal class actions than any other type and more of this type than any other justice.

Kennedy was also a leader among justices covered in this dataset for another reason. As with much of the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence over the last decade and a half, Kennedy authored the majority opinion in more close class-action cases than any other justice.

Scalia wrote for the court in more 5-4 and 5-3 cases than cases decided by any other type of split vote, while Thomas wrote an equal number of opinions for the court in 5-4 and unanimous cases. The more liberal justices on the court all wrote opinions for the court more often in unanimous cases than in cases with split votes.

Certain attorneys, especially prominent repeat players before the Supreme Court, most frequently argued these cases.

The most frequent oral advocates include David Frederick with nine arguments, Tom Goldstein and Paul Clement with eight, and Neal Katyal, Malcolm Stewart, and Carter Phillips with four each. These attorneys specialized within this case set, as several argued multiple cases within the same class-action subject areas.

Tom Goldstein and David Frederick argued the most cases in the securities area, with five and four arguments respectively. David Frederick also had two arguments in employment-related cases. One other attorney, Paul Clement, had several arguments in multiple subject areas: two each in consumer, employment and securities cases.

With Kennedy now retired, the dimensions of these cases have shifted. No longer will attorneys look to swing Kennedy’s vote in close cases, as they will instead have to look towards another justice for decisive votes. Some of the attorneys who argued several of these cases no longer argue before the Supreme Court as frequently, while others still regularly argue multiple cases each term. Certain trends in the types of cases the court has heard over the last several terms may help indicate the types of class-action disputes the court is likely to hear in upcoming terms. Areas like employment arbitration, for example, might be high on the list, as the court has heard several of these cases in each of the last two terms. Other cases that started as class actions are already on the slate for the court’s 2019 term. Among these, Retirement Plans Committee of IBM v. Jander will be argued during the court’s November sitting. Other such cases are already in the court’s pipeline.

This post was originally published at Empirical SCOTUS.

Posted in Empirical SCOTUS