Justice Stevens at oral argument: Often fatal; always kind

on Jul 19, 2019 at 1:18 pm

Paul Clement is a partner in the Washington, D.C., office of Kirkland & Ellis LLP. Clement served as the 43rd Solicitor General of the United States from June 2005 until June 2008.

In looking back at Justice John Paul Stevens’ remarkable life and tenure on the Supreme Court, there are many ways to try to capture his enduring contribution to the court and its jurisprudence. Perhaps the most obvious metric is to look to his many influential opinions for the court, of which there is no shortage. Every lawyer has a favorite, but there is no denying the importance of his opinions for the court in cases like Chevron U.S.A. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Apprendi v. New Jersey and Clinton v. Jones.

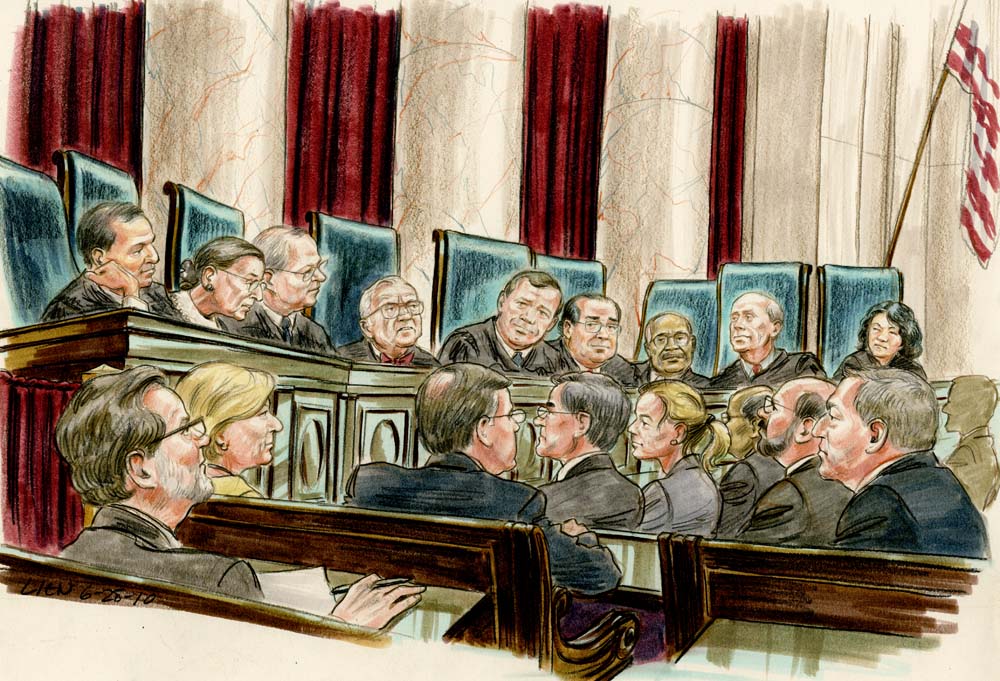

As Justice John Paul Stevens prepared to read his farewell letter in 2010 he noted that when he joined the court in 1975 such a letter could well have been addressed “Dear Brethren,” but with two women on the court — likely to be joined by a third — he began with “Dear Colleagues.” (Art Lien)

One could also point to Justice Stevens’ role as one of the Supreme Court’s great dissenters. Those separate writings had immediate benefits for the court in forcing the sharpening and refinement of the majority’s reasoning. They also could have a long-term impact on the development of the law. Take, for example, Justice Stevens’ solo dissent in United States v. Watts, a 1997 decision in which a majority of the court dispatched a challenge to the use of acquitted conduct to enhance a sentence under the Sentencing Guidelines in a per curiam opinion. If you look at Justice Stevens’ dissent in that case, you can identify all of the basic elements of the reasoning in the Apprendi-Blakely-Booker line of cases, three years before and four votes shy of his majority opinion in Apprendi. Indeed, much of that reasoning was evident in his dissent in McMillan v. Pennsylvania 11 years earlier.

There are plenty of other aspects of Justice Stevens’ life and tenure that deserve emphasis, but others are better positioned to address them. There is, however, one aspect that I would like to highlight: namely, his questioning of advocates at oral argument. The justices all have their unique styles of questioning advocates – some prefer hypotheticals, others focus on precedents – but there is no justice who combined a kind and gentle manner with an ability to cut to the heart of a case and the weakness of an advocate’s position quite like Justice Stevens. His questions so often started with an unassuming and gentle lead-in and ended with the lawyer conceding his or her case without even realizing it.

Indeed, Justice Stevens routinely prefaced his questions with statements like: “May I ask just one more question?” Or: “May I ask about just one thing in the record I am not sure I understand?” Or even: “May I ask you what is probably a stupid question?” It is hard to imagine that last lead-in coming from many others with Article III tenure and salary protection. Indeed, I think there is (or should be) something in the Supreme Court’s Guide for Counsel to the effect that there is no such thing as a stupid question from a justice, only a stupid answer from an advocate.

Counsel were occasionally lulled into a false sense of security by such humble lead-ins. Having watched Justice Stevens in a large number of arguments, no matter how they are labeled, his questions were always highly intelligent and often fatal. But the questions also reflected an appreciation of the practical difficulties that arguing counsel sometimes face. When Justice Stevens asked a question late in the petitioner’s argument, it was often prefaced with an observation, that he saw that the white light is on or knew that time is running low, but he had just one more question. Such a lead-in paved the way for a relatively brief answer and no doubt served as a reminder to any number of lawyers that reserving time for rebuttal would be a capital idea.

Justice Stevens could also be remarkably kind when a lawyer came up short in answering a question. In one case, Justice Stevens was setting up a particularly devastating question with a seemingly innocuous one about when the statute at issue in the case was enacted. The advocate clearly had no idea. While the justice could have chastised the advocate for not knowing a fairly basic piece of information, Justice Stevens instead simply asked a follow-up: “Well, it was a good many years ago, wasn’t it?” In a similar vein, when an advocate committed the cardinal sin of referring to a justice as a judge – this in the face of a specific and italicized admonition in the court’s Guide to Counsel not to do so – Justice Stevens observed that Article III of the Constitution makes the same mistake.

On a personal note, Justice Stevens was unfailingly kind and courteous to me both on and off the bench. He did not always agree with the position I advocated, but he always engaged with a smile and an appreciation for a responsive, if not entirely satisfying, answer. And both early in my service in the Office of the Solicitor General and when I completed my service, he went out of his way to convey a personal message of encouragement.

Before Justice Stevens’ three and a half decades on the Supreme Court and four decades on the bench, he was a highly accomplished practitioner. Among the many remarkable things about Justice Stevens is that during 40 years on the bench he never lost his understanding of and sympathy for the challenges that faced the advocate on the other side of the bench. And, for that, there were a lot of grateful advocates, myself certainly included.