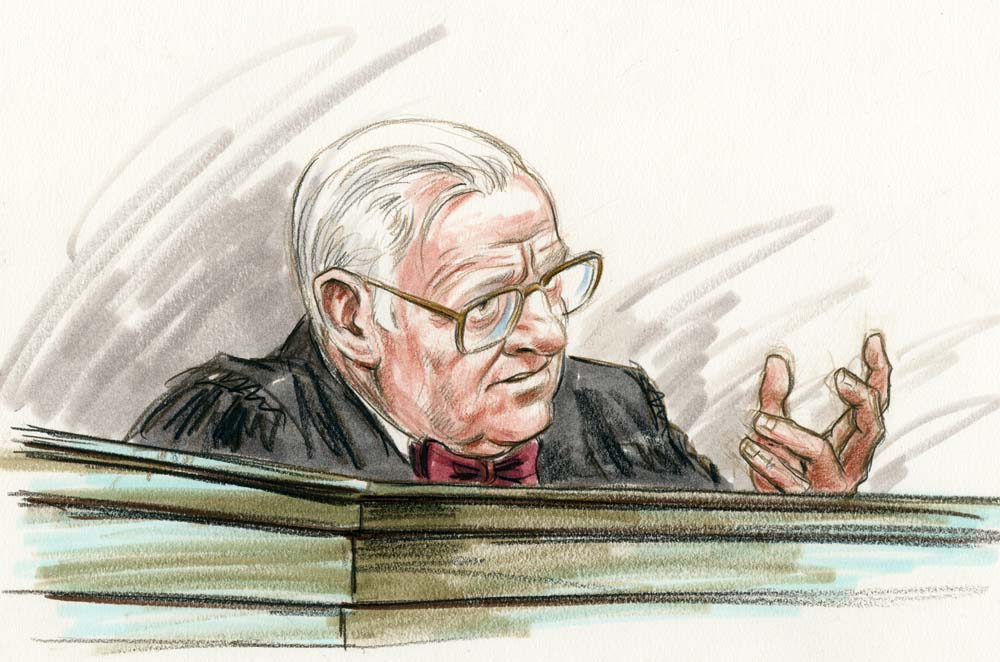

Justice Stevens: A habit of understanding before disagreeing

Joseph Thai is a law professor at the University of Oklahoma. He clerked for Justice John Paul Stevens during the October 2000 term.

A decade after clerking for Justice Wiley Rutledge during the October 1947 term, John Paul Stevens wrote that the characteristically long opinions of his former boss could be “exasperating to a hurried practitioner seeking a succinct statement of a ‘true rule.'” That admission was not criticism, however. Those lengthy opinions to Stevens evidenced “two virtues of a great judge—tolerance and judgment.” As he explained, their “full statement of the opposing argument and countervailing considerations,” as well as their “full statement of all the factors which lead to and qualify the result,” reflect a judicious “habit of understanding before disagreeing.”

Stevens himself unfailingly exhibited that habit over half a century later when I clerked for him.

Foremost, the habit of understanding before disagreeing showed in how Justice Stevens worked on each case. He began by reading the briefs himself so that he could study the parties’ arguments directly, relieving us clerks of the task of writing bench memos summarizing them. That habit also shaped how he discussed cases with us prior to oral argument. He would always ask first what we clerks thought before offering his own views. When it was his turn, he would often open with a “Yes, but what about …” to get our thoughts on a fact or argument that we may have overlooked or that was carrying more weight with him. When we interrupted him — which, I wince to recollect, we did frequently — he stopped without hesitation to hear what we had to say, even though we were barely-minted lawyers and he had served as a judge longer than we had lived. And when any of us, or sometimes all of us, disagreed with him, he would continue the discussion until one side or the other could be persuaded or, failing that, he could be satisfied with the reasons why he was (with a chuckle) “once again in dissent.”

Justice Stevens’ habit of understanding before disagreeing extended to oral argument. I cannot recall one in which he asked the first question, but I recall many in which he asked one of the last, after the hot bench had cooled down. And as advocates before him have observed, his questions were always fair, if sometimes fatal. But that was because he had gotten to the point of understanding at which he could cut to the heart of the case.

Of course, Justice Stevens’ habit carried over into his opinion writing. He was known for writing the first drafts of his opinions at a time when most justices delegated that vital task to law clerks. It was not a distinction he sought out, but a duty he performed to ensure that what he thought he believed could survive the critical process of writing. On some occasions, his writing did lead him to change course. Regardless, his opinions, like those of Justice Rutledge, were often long.

Toward the end of the term, in an episode of procrastination, my co-clerks and I counted the number of concurring and dissenting opinions that our boss had authored so far. For our contentious term, which included Bush v. Gore, that number was rather high. When we disclosed the tally to him, he looked surprised and, with a self-deprecating laugh, professed, “That’s embarrassing.” But he kept at it. And because he kept writing separately to explain himself — even after retiring from the Supreme Court — others could come to understand his considered views, even if they might not agree.

In our divided, heated times, the habit that Justice Stevens inherited from his judicial mentor seems increasingly out of practice, if not also out of date. For that reason, it is at least worth commemorating.

Posted in Tributes to Justice John Paul Stevens