Opinion analysis: Felons-in-possession must know they are felons

In order to convict an unauthorized immigrant for gun possession, a federal prosecutor must prove not only that the defendant knew he possessed the gun but also that he knew he was out of immigration status, the Supreme Court ruled 7-2 on Friday in Rehaif v. United States. The decision will almost certainly lead to collateral attacks on convictions under a much more commonly invoked provision criminalizing gun possession by convicted felons.

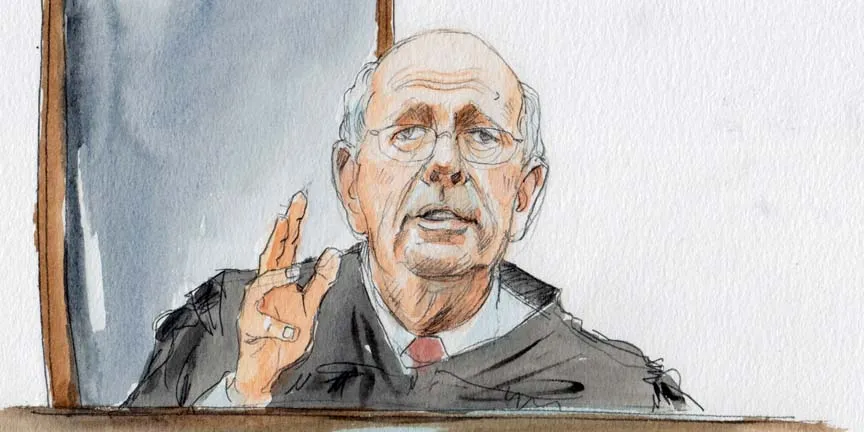

Justice Stephen Breyer’s majority opinion stated that the federal law in question, 18 U.S.C. § 922(g), criminalizes possession of firearms by a person falling into any of nine enumerated status categories, one of which is aliens unlawfully in the United States, and another of which is anyone convicted of an offense punishable by at least a year in prison. The majority explicitly held that the government “must show that the defendant knew he possessed a firearm and also that he knew he had the relevant status when he possessed it.”

In a vehement dissent, Justice Samuel Alito, joined by Justice Clarence Thomas, protested that the decision will lead to a flood of challenges by people currently incarcerated under Section 922(g), most of them in the felon-in-possession category. Noting that 6,032 people were convicted in fiscal year 2017 alone under Section 922(g), with an average sentence of 64 months, Alito warned of a coming flood of litigation. Those whose direct appeals are not yet exhausted will “likely be entitled to a new trial,” said Alito, and others will move to have their convictions vacated under 28 U.S.C. § 2255.

Alito specifically outlined the group of prisoners who could file under Section 2255. “[T]hose within the statute of limitations will be entitled to relief if they can show that they are actually innocent of violating Section 922(g), which will be the case if they did not know that they fell into one of the categories of persons to whom the offense applies,” he wrote. “If a prisoner asserts that he lacked that knowledge and therefore was actually innocent, the district courts, in a great many cases, may be required to hold a hearing … and make a credibility determination as to the prisoner’s subjective mental state at the time of the crime.”

Petitioner Hamid Rehaif will be among those who get a hearing on whether he actually knew he was out of immigration status. He had come to the United States on a student visa to study at a university in Florida, but he was academically dismissed. In informing him about his dismissal, the university’s email notified him that his immigration status would be terminated if he did not transfer to another school or leave the United States, neither of which he did. Instead, he stayed in Florida. During that stay, he went to a firing range, purchased ammunition and fired weapons. Hotel staff tipped off the FBI that Rehaif was engaging in suspicious behavior.

At the ensuing trial, the district court instructed the jury that it need not find that Rehaif knew he was out of immigration status, and the jury convicted. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit affirmed, noting substantial agreement among its fellow circuits that the term “knowingly” in 18 U.S.C. § 924(a)(2) applies to possession of the weapon, but not to the status category of the possessor.

Breyer’s majority opinion rejected that position. “In determining Congress’ intent, we start from a longstanding presumption, traceable to the common law, that Congress intends to require a defendant to possess a culpable mental state regarding ‘each of the statutory elements that criminalize otherwise innocent conduct,'” wrote Breyer. “Here we can find no convincing reason to depart from the ordinary presumption in favor of scienter [requirement of guilty mind].”

The phrase “otherwise innocent conduct” strongly echoed concerns voiced by Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh at oral argument. They had noted that possession of a gun alone is not blameworthy and therefore that one’s membership in a prohibited status category is all that stands between innocent and criminal conduct under Section 922(g). If the status divides innocent from criminal conduct, then the defendant should have to know of that status in order to be convicted, they suggested. Along those lines, the majority opinion acknowledged that the statute’s “harsh” maximum punishment of 10 years played a role in its decision.

Now that the court has decided that knowledge of status is required for a conviction under Section 922(g), prosecutors must think about what kinds of tangible evidence can be used to show that state of mind, and those looking to challenge their convictions must scour their records to find some evidence casting doubt on the existence of such knowledge. These tasks are complicated greatly by the fact that there are nine different status categories. While reminding prosecutors that they may prove state of mind through circumstantial evidence, the majority refused to get too specific, saying, “We express no view … about what precisely the Government must prove to establish a defendant’s knowledge of status in respect to other Section 922(g) provisions not at issue here.”

However, the majority opinion did mention two hypothetical fact scenarios in which there could be reasonable doubt that the defendant knew his status. Echoing a remark by Justice Sonia Sotomayor at argument, the majority pointed out that a failure to require knowledge would criminalize firearm possession by “an alien who was brought to the United States unlawfully as a small child and was therefore unaware of his unlawful status.” The court made the same observation about “a person who was convicted of a prior crime but sentenced only to probation, who does not know that the crime is ‘punishable by imprisonment for a term exceeding one year.'” This would seem a particularly important scenario, given that the vast majority of convictions occur by plea bargain, where the lawyer, not the defendant, does the negotiating. Moreover, the average defendant’s curiosity only extends to the prosecutor’s actual offer, not to the theoretical maximum punishment that the prosecutor could have sought under the statute.

The dissent expressed concerns that the majority’s decision will lead gun owners to keep themselves in the dark about their membership in Section 922(g) status categories. “Consider a variation on the facts of the present case,” wrote Alito. “An alien admitted on a student visa does little if any work in his courses. When his grades are sent to him at the end of the spring semester, he deliberately declines to look at them. Over the summer, he receives correspondence from the college, but he refuses to open any of it. He has good reason to know that he has probably flunked out and that, as a result, his visa is no longer good. But he doesn’t actually know that he is not still a student.”

The majority did not address this hypothetical, but it seems extremely unlikely that such a gambit would succeed. Model Penal Code Section 2.02(7) addresses the very situation contemplated by the dissent, sometimes referred to as the “ostrich defense” — sticking one’s head in the sand and then pleading ignorance of incriminating facts. Under this provision, because the hypothetical student was aware of a “high probability” that he was out of immigration status, his refusal to confirm that fact will not prevent a conclusion that he knew it.

Although nothing in the Model Penal Code is legally binding on its own accord, it seems unlikely that the court would reject Section 2.02(7). After all, the majority openly relied on Section 2.02(4) to support its conclusion that the term “knowingly” should apply to all nonjurisdictional elements of the offense. Perhaps more importantly, if the ostrich defense were permitted in Section 922(g) cases, it would be hard to explain why that gambit should not be permitted to defeat the knowledge requirements in hundreds or thousands of other criminal statutes nationwide.

Posted in Merits Cases

Cases: Rehaif v. United States