Empirical SCOTUS: Wild ride of a term with 20 decisions still to go

The October 2018 Supreme Court term has taken many twists and turns, and the court still has 20 decisions to release in its last week and a half of work before the summer recess. Much may change between now and then, but with 55 cases already decided, we have unique and surprising patterns of decision-making among the justices. This is most apparent in the court’s 5-4 (or 5-3) decisions, in which one vote could shift a decision in a different direction. The court’s 5-3 and 5-4 decisions this term include Madison v. Alabama, Stokeling v. U.S., Nielsen v. Preap, Lamps Plus Inc. v. Varela, Washington State Department of Licensing v. Cougar Den Inc., Bucklew v. Precythe, Apple Inc. v. Pepper, Herrera v. Wyoming, Franchise Tax Board of California v. Hyatt, Home Depot U.S.A. Inc. v. Jackson, Manhattan Community Access Corp. v. Halleck, Mont v. U.S. and Virginia House of Delegates v. Bethune-Hill. So far, these decisions and the court’s majority compositions in general have not gone as many predicted.

The justices have aligned in eight different majority compositions in these 13 decisions. The only alignment that has voted together in more than two decisions is the one composed of the five more conservative justices – Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh.

When examined another way, however, the different compositions suggest a new method for the liberal justices whereby they seek a fifth vote among the conservative justices to secure a 5-4 majority. Six of these compositions included all four of the more liberal justices in the majority and a swing vote from one the more conservative justices.

Although the tactics for securing this fifth vote may have led the liberals to account for more diverse views in the majority opinions, they have also led to a higher rate of success in these cases than many expected prior to the term. This is evident below as we break down the 5-3 and 5-4 ideological compositions for these 13 decisions.

Four different conservative justices voted along with the liberals in six different compositions, and the only conservative who has yet to vote along with the four liberals in a five-justice majority, this term or ever, is Alito.

This is actually the first time in the Roberts Court era that four different conservative justices provided a swing vote to liberal majorities in 5-3 and 5-4 decisions in a term when nine justices sat on the court (There were four different compositions in 2005, but there were also 10 justices on the bench that term, as Justice Sandra Day O’Connor departed in the middle of the term and Alito took her seat before the term’s end.). The figure below shows swing justices for both liberal and conservative coalitions from the 2005 term through the 2017 term (The Supreme Court Database supplied much of the pre-OT 2018 data.).

These swing justices are defined as follows: The more conservative coalitions included Justice Antonin Scalia, Thomas, Alito and Roberts through the middle of the 2015 term, and then Gorsuch from the end of the 2016 term forward. A fifth justice voting alongside one of these groupings of four was noted as the swing. The more liberal coalitions included Justices David Souter, John Paul Stevens, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer until 2009, then Justice Sonia Sotomayor, Stevens, Ginsburg and Breyer in 2009, and Sotomayor, Justice Elena Kagan, Ginsburg and Breyer for the 2010 term forward. Similar to the conservatives’ swing justices, a swing for the liberals voted along with one of these groupings of four liberal justices.

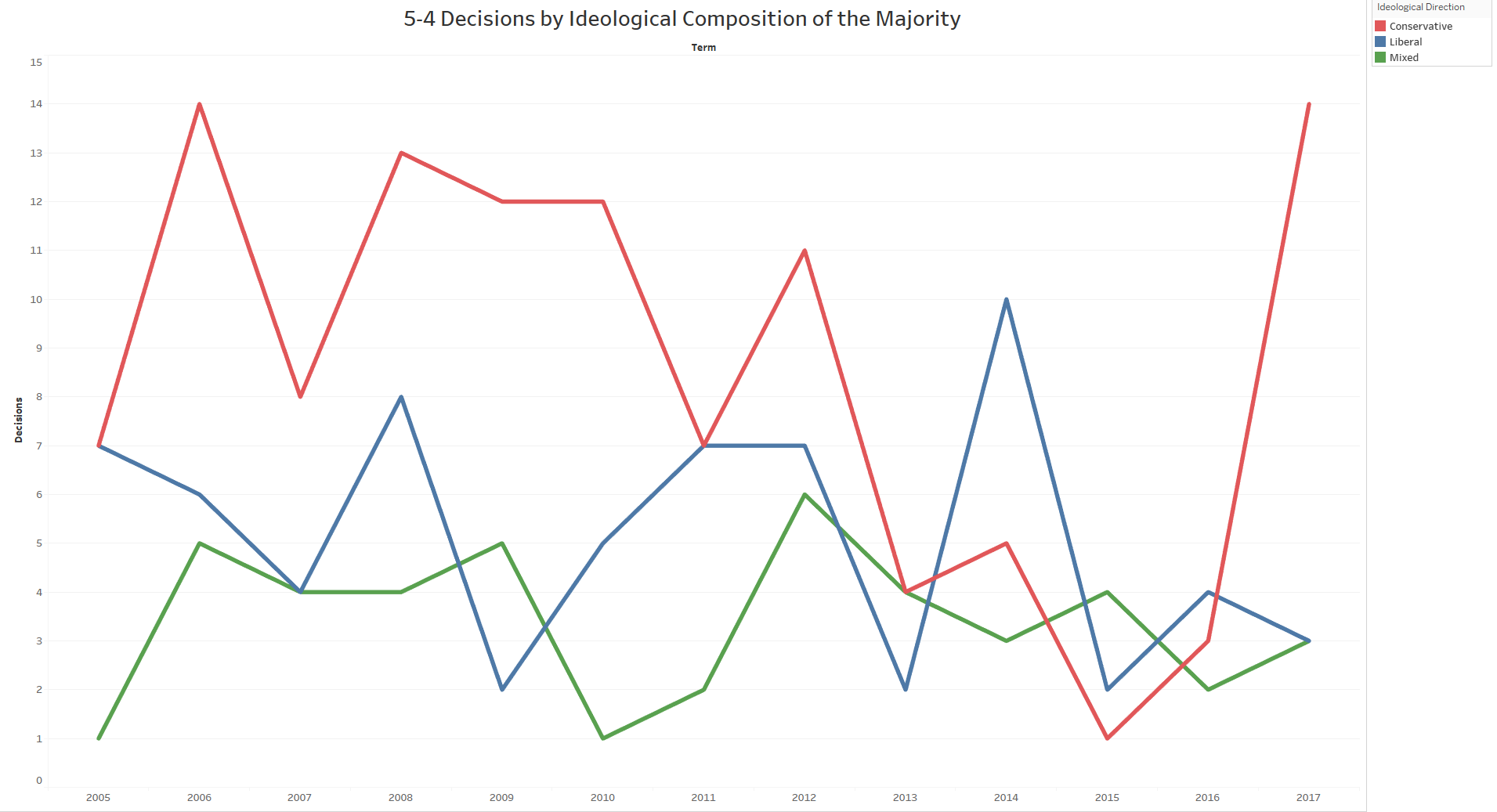

This can also be visualized by combining the justices into liberal, conservative and mixed 5-4 and 5-3 coalitions for the 2005 through 2017 terms. When organized in this fashion the graph looks as follows:

Last term, when Justice Anthony Kennedy still sat on the court as the potential swing justice, the more liberal justices’ rate of success in 5-3 and 5-4 decisions was actually much lower than in past, as Kennedy did not vote with the liberals in any of these close decisions.

Another unique quality of these close decisions is the number of different majority compositions of justices. The eight different five-justice majorities this term are the most we’ve seen during any Roberts Court term, and there are still 20 decisions left to be released.

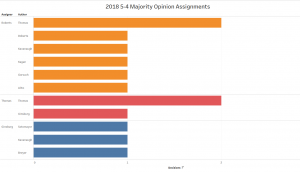

Finally, the diversity of authorship in 5-3 and 5-4 decisions is also readily apparent. With Kennedy no longer taking the bulk of these opinion assignments, these opinions are split more evenly among the justices. Thomas has written the most such decisions so far this term with four, and Kavanaugh is the only other justice who has written more than one 5-4 or 5-3 majority opinion (with two so far), while the remaining seven other justices each wrote one such decision apiece.

Keeping the focus on Thomas for a minute, the greatest number of 5-4 decisions he wrote in a previous term was four in 2006 and in 2010. If he writes another 5-4 majority opinion out of the court’s remaining 20 decisions, he will have written five 5-4 majority opinions for the first time in his 28 terms on the court.

The chief justice assigns majority opinions when he is in the majority, and otherwise the most senior justice in the majority assigns opinions. Three different justices have assigned the majority opinions in 5-4 and 5-3 decisions this term.

Two of Thomas’ decisions were self-assigned and two were assigned by Roberts. Kavanaugh had one opinion assigned by Roberts and one by Ginsburg.

Looking at past opinion assignments during the Roberts Court years, we may note that Thomas had only assigned himself to write one 5-4 majority opinion prior to this term. This was in the 2012 decision Alleyne v. U.S. The horizontal axis below shows assigning justices (and terms on the bottom), while the vertical axis contains the authoring justices.

The patterns described above are designed to trace changes in the court’s behavior from previous terms to the current one and nuances that might have gone otherwise unnoticed. They also are meant to highlight areas worthy of attention between now and when the court completes its business for the 2018 term next week.

This post was originally published at Empirical SCOTUS.

Posted in Empirical SCOTUS