Argument analysis: Justices grapple with immoral and scandalous trademarks

On Monday, the Supreme Court considered the intersection of free speech and trademark law when it addressed the constitutionality of prohibiting trademark registration for offensive trademarks. This case arose in the aftermath of Matal v. Tam. In Tam, the court struck down the Lanham Act’s prohibition on registration of disparaging trademarks, holding that the ban constituted viewpoint discrimination in violation of the First Amendment. The question before the court on Monday was whether the prohibition on federal registration of immoral or scandalous trademarks is similarly facially invalid under the First Amendment. Both sides faced a hot bench.

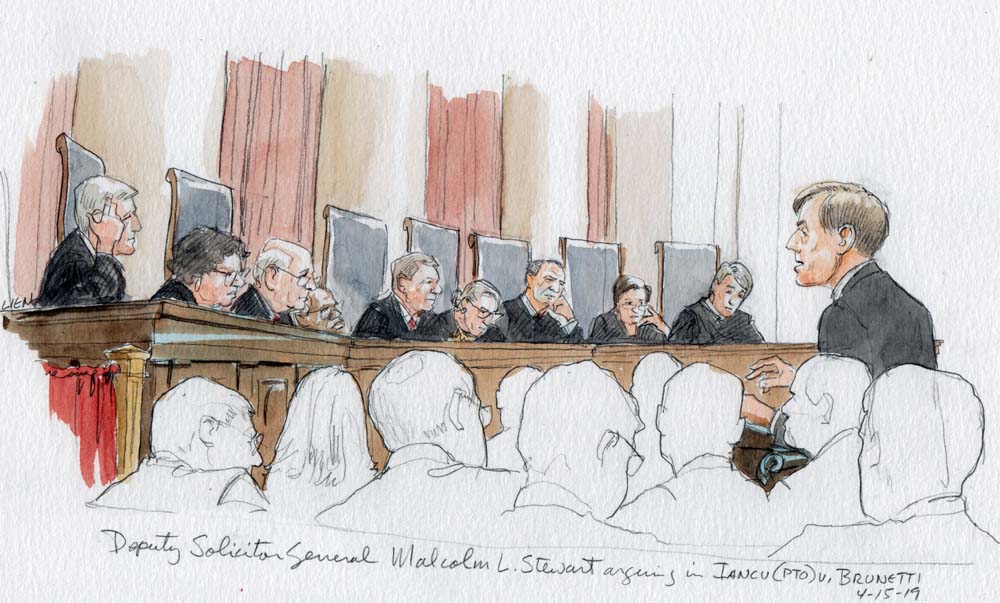

One thing seemed clear: No one particularly liked the statute as it has been interpreted over time. Deputy Solicitor General Malcolm Stewart argued on behalf of the government. Stewart conceded that the evaluation of immoral or scandalous trademarks under the Lanham Act has encompassed material that is offensive or shocking because of the “outrageous views” that language expresses, and that such viewpoint discrimination is “not a valid basis for denial of federal registration of a trademark.”

However, Stewart argued that although the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office has previously defined scandalous as encompassing marks that are “shocking,” “offensive,” “disgraceful” and “disreputable,” going forward the agency would read the statute more narrowly, limiting it to terms that are shocking or offensive because of their “mode of expression,” rather than the “ideas that are expressed.” Multiple justices were troubled by that argument. Justice Elena Kagan was particularly concerned about the implications of upholding a statute on the basis of the government’s promise not to enforce the statute to the full breadth of its language: “[T]hat’s a strange thing for us to do, isn’t it, to basically … take your commitment that … these are very broad words, but we’re going to pretend that they say something much narrower than they do?” Chief Justice John Roberts emphasized multiple times in questioning that this is a facial challenge to the statute.

The justices queried Stewart about the governmental interest at stake here. Justice Samuel Alito asked whether the government’s interest is focused on preventing an association with particular words, or is based on a sense of the public’s morality. Stewart asserted that the governmental interest is twofold: protecting unwilling viewers from material they find offensive, and not having a governmental association with certain words. Alito and Justice Sonia Sotomayor pushed back on the first rationale, pointing out that trademarks can be used in commerce whether or not they are registered, and that rejecting a trademark registration does not remove it from the stream of commerce.

Problems with the statute’s language and application over time were raised by Justices Brett Kavanaugh, Neil Gorsuch and Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Ginsburg noted on two occasions the difference in perception of trademarks depending on the market audience; consumers of FUCT merchandise may find the mark “mainstream.” Gorsuch was particularly troubled by inconsistencies in acceptances and rejections in the PTO’s application of this provision over time, and the resultant inability to give adequate notice to trademark owners. He asked Stewart how a person who wants to develop a brand is supposed to predict what the PTO is going to do. He added that he himself could not “see a rational line” through the refusals and registrations, and asked “is it a flip of the coin?” Stewart defended the inconsistencies by explaining that trademarks are evaluated in context, and marks differ in appearance and presentation, and in the particular goods and services at issue.

Despite widespread concerns with the statutory language and application, several justices expressed apprehension about opening the floodgates to profanity and offensiveness in the marketplace. Roberts asked whether trademarks that are obscene could be prohibited if the statute were struck down, and Stewart responded that he did not think so. Alito, who authored the plurality opinion in Tam, was concerned about an increased flow of applications that might result if the court strikes down the statute: “[I]f this is held to be unconstitutional, what is going to happen with whatever list of really dirty words still exist and all of their variations?”

When John Sommer, counsel for Erik Brunetti, stepped up to the plate, he faced a similarly active round of questioning. The justices grappled thoughtfully with the contours of conflict: There is the statute, as written and as applied, which everyone in the room seemed to view as a problem. However, is it appropriate to have no line at all?

The court expressed concern that allowing trademark registration for offensive terms would be perceived as some sort of government endorsement. Justice Stephen Breyer wanted to know more about the harm presented by the statute to trademark owners, and stressed the physiological impact of certain words, asking why the government couldn’t refuse to be associated with those kinds of words. Kagan inquired whether a statute applied in a way so as to prohibit only profanity would pass constitutional muster. Sommer responded that obscenity could, in fact, be barred from registration. Kavanaugh asked how we would procedurally apply an obscenity standard to trademarks, and Sommer suggested that Miller v. California would govern. Alito explored the possibility of a narrowed list of prohibited terms, such as George Carlin’s “seven dirty words.” Sommer cautioned against applying an abstract list, given inconsistencies in the application of the current statute with regard to such terms, and suggested that because of viewpoints expressed in these marks, “if Congress were to pass that, we’d be here again in a few years.”

The court explored the contours of viewpoint with regard to offensive terms. Is “giving offense a viewpoint” here, as Alito wrote in the Tam case, or does that language apply in a different, or more limited, set of circumstances? Although racial slurs would seem to fall within the ambit of Tam, Breyer worried that racial slurs would appear on buses, on newsstands in Times Square, and in places where children would see them. He didn’t agree that racial slurs express a particular viewpoint; rather, they are “used to insult somebody, rather like fighting words,” or “to call attention to yourself.” Kavanaugh asked Sommer about the overlap of insult with viewpoint, and Sommer responded that, although the “traditional exceptions to free speech, such as fighting words,” do not express viewpoint, insulting someone is different, as the court decided in Tam. The nature of the relationship between disparaging trademarks and immoral or scandalous trademarks has been unclear for decades in PTO decisions, and the justices appeared to wrestle here with the distinction, as well.

Roberts raised the issue that the trademark registration system is content-based, including other bases for rejection — that the purpose of the program is to regulate content. Sommer agreed with Roberts and Kagan that other provisions of the Lanham Act are content-based and would require constitutional analysis.

As the argument drew to a close, Gorsuch asked Sommer to explain whether he had met the burden of a facial challenge. Sommer asserted that he had demonstrated that a substantial amount of protected speech is improperly refused under the provision, including both political and religious speech. On its face, he said, even the trademark “Steak ‘n Shake” could be refused registration under this provision, because a substantial composite of the general public believes that eating meat is immoral.

The government’s rebuttal focused on two points: racial slurs and content-based distinctions. First, Stewart emphasized that although the PTO views Tam as generally prohibiting denial of registrations for racial slurs, the office is holding back on applications for the “single-most offensive racial slur” pending the outcome of this case. Second, Stewart noted that content-based distinctions are ubiquitous in the registration program.

Posted in Merits Cases

Cases: Iancu v. Brunetti