A “view” from the courtroom: Dangling past participles

on Apr 15, 2019 at 4:44 pm

The first case for argument today involves the highly provocative trademark, “FUCT,” for a line of “streetwear” founded by Erik Brunetti in California in 1990.

Brunetti’s lawyer, John Sommer, promised in his merits brief that references to “vulgar terms” will be not be necessary during oral arguments, or if necessary, “the discussion will be purely clinical, such as when medical terms are discussed.”

At the end of the hour, he will turn out to be right, though the lawyers and the justices will perform some mental gymnastics to avoid the use of Brunetti’s trademark and other profane or vulgar terms.

Sommer has pre-empted the warning that has typically come from the court about not using profane or vulgar language during arguments in past cases involving Paul Cohen’s “F**k the Draft” message on the jacket he wore in a courthouse, George Carlin’s “Filthy Words” routine (or the “seven words you can’t say on the public airwaves”), and the “isolated utterances” of obscene words on television.

An amicus brief on Brunetti’s side from the Cato Institute, besides offering its own thoughtful take on the importance of vulgar language in society, directs readers to a fascinating article in a 2012 issue of the William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal by Thomas Krattenmaker, who was a law clerk to Justice John Marshall Harlan. In Cohen v. California, Harlan (and mostly Krattenmaker, by his account) wrote the opinion for the court that said the anti-draft message on the jacket was protected from criminal prosecution by the First Amendment.

Krattenmaker relates the well-known fact that before oral argument in Cohen in the fall of 1970, then-Chief Justice Warren Burger sought to head off the use of the offending word by telling Cohen’s lawyer that the justices were familiar with the facts of the case. But the lawyer, Melville Nimmer, used the word in response to the first question he received. Krattenmaker further relates that Nimmer worried that court security personnel might jump up and say, “He said F*** in the Supreme Court, grab him!”

No one grabbed Nimmer that day, of course.

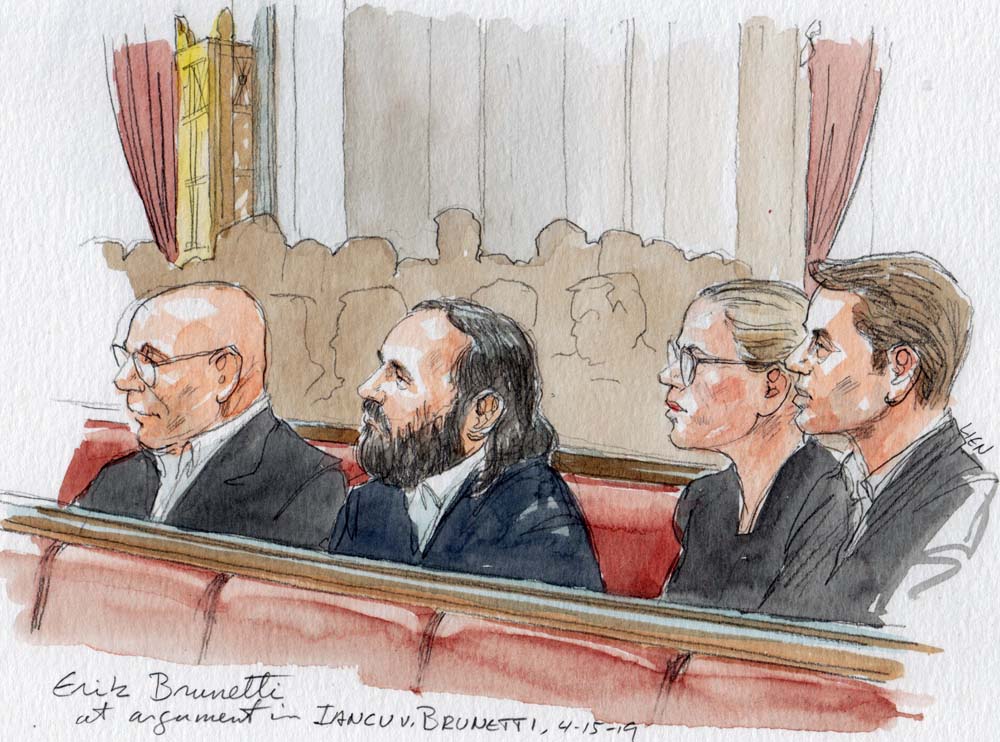

Today, Erik Brunetti is in the courtroom. If he is wearing one of his infamous T-shirts, it isn’t evident. He’s in the second row of the middle section of the public gallery, right behind the front row that almost always is kept empty. He will listen intently to the argument.

There’s another person who has caught our eye this morning. George Conway, the sometimes news-making husband of Kellyanne Conway, a counselor to President Donald Trump, is in the last row of the bar section. Conway, a partner with Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz, appears to have more of a connection to the second case for argument today: Emulex Corporation v. Varjabedian, a securities case. Conway is the counsel of record for an amicus brief filed by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the Business Roundtable in support of Emulex.

There are also a handful of children in the public gallery, and high school students churning through the three-minute section in the back of the courtroom. Their ears will mostly not need shielding today.

As the argument in Brunetti gets going, there is a derby of sorts among the justices and the lawyers for creative ways to avoid mentioning the trademark at issue in the case. (I’m generally using “Brunetti’s mark” as my polite substitute.)

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg refers to “what’s involved in this case,” and mentions the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s standard of refusing trademark recognition to a mark under the scandalous provision when a “substantial composite of the general public” would find it shocking or offensive.

Would a composite of 20-year-olds find Brunetti’s mark shocking, she asks Deputy Solicitor General Malcolm Stewart.

He agrees some segments of the population would be less shocked than others. But the PTO, he says, determined that “this mark would be perceived by a substantial segment of the public as the equivalent of the profane past participle form of a well-known word of profanity and perhaps the paradigmatic word of profanity in our language.”

A little later, Stewart will refer to George Carlin’s “Filthy Words” monologue as “a paradigmatic example of profane copyrightable expression.”

“Now our society has reached a good accommodation where people who find the Carlin monologue funny or thought-provoking can buy the CDs, they can buy the DVDs,” he says, dating his technology frame of reference a bit. “When Carlin was alive, they could watch live performances. All that can be done without forcing the profanity upon anybody who finds it offensive.”

One thing the justices seem to agree on this morning is that the Trademark Office has been thoroughly inconsistent in its treatment of trademark applications involving the “seven dirty words” and their variations.

Justice Neil Gorsuch refers to the appendix at the end of Brunetti’s merits brief, which provides a four-page guide to those inconsistencies with examples that would make any sailor blush.

“There are shocking numbers of ones granted and ones refused that do look remarkably similar,” Gorsuch says.

(The appendix is part of the printed “red brief,” but is a separate document in the court’s docket for the case. Parental Guidance suggested. And by that, we mean that some parents may need to consult their 20-something children for explanations.)

We weren’t surprised to learn that the motto on the wallet of Samuel L. Jackson’s character (Jules) in “Pulp Fiction” was rejected for federal trademark protection. (As Jules puts it in the classic 1994 Quentin Tarantino film, “It’s the one that says ‘Bad Mother F*****.’”)

When Stewart starts to discuss an example by spelling out a phonetic equivalent for the profane past participle form of the word at issue, Gorsuch cuts him off.

“I don’t want to go through the examples. I really don’t want to do that,” he says to laughter from the courtroom.

Justice Stephen Breyer raises a serious concern about “racial slurs” and he gets a bit clinical.

“I’ve looked into [it] a little, and there are certain ones that have exactly the same physiological effect on a person, if any, as the word we’re using here, and there is a physiological effect.”

It becomes clear he is talking about the N-word, which he and Stewart want to avoid mentioning even more than Brunetti’s trademark.

Stewart will say later that even after the court’s decision in Matal v. Tam found that the Lanham Act’s disparagement provision violated the First Amendment, the PTO is holding back on approving any trademarks related to that word as potentially violative of the scandalous provision.

Sommer, whose day job is as general counsel of the Stussy line of clothing, takes to the lectern, and Breyer soon continues his clinical discussion of the effects of certain words on the brain, including forms of Brunetti’s mark and certain racial slurs.

“They have a different physiological effect on the brain,” Breyer says of these words. “They’re stored in a different place. They make a difference in the conductivity of your skin, which shows emotion, and above all, they are remembered.”

Why can’t the government say it doesn’t want to be associated with such words, by refusing them trademark recognition, Breyer asks.

Sommer argues repeatedly that the government is making viewpoint-based distinctions. When he says that his client’s mark “isn’t exactly one of the seven dirty words,” Alito objects.

“Oh, come on,” he says. “Be serious. We know … what he’s trying to say.” Would any “clever way” of avoiding a list of seven banned words be okay?

Sommer points out that there are other variations of Brunetti’s mark that have won trademark recognition, such as “FCUK,” by the French Connection UK clothing chain.

Alito agrees that the PTO has inconsistently applied the standards, but asks whether going forward there can be a list of prohibited words and “you just can’t use those. And your position is that would be unconstitutional?”

“I think so,” Sommer says. “If Congress were to pass that, we’d be here again in a few years to determine whether that’s true.”

Sommer mentions that his client’s goods are not exactly sold at Walmart. (Actually, Brunetti has said in recent interviews that they’re now sold exclusively online, with new products each month that usually sell out within days. Still, it’s our general impression that Brunetti’s line is somewhat past its prime.)

Chief Justice John Roberts tells Sommer that even if Brunetti’s shirts aren’t sold at Walmart, they’re “going to be worn on people walking down through the mall. And, you know, for parents who are trying to teach their children not to use those kinds of words, they’re going to look at that and say, well, look at that, and then, you know, they’re going to see the little trademark thing and say, well, it’s a registered trademark.”

The courtroom erupts in laughter.

“Well, they won’t say that,” the chief justice adds, “but you understand my point is that the government’s registration of it will facilitate its use in commerce, not necessarily speech, but as a commercial product, and that has consequences beyond … where the product is sold.”

Sommer says a little later that “the audience that Mr. Brunetti is appealing to is young men who want to be rebels. And this is how they do it.”

“Well, that may be the audience he’s targeting,” Roberts says. “But that’s not the only audience he reaches.”