Argument analysis: Sorting out a thorny statute-of-limitations question in False Claims Act case

on Mar 19, 2019 at 5:19 pm

The Supreme Court engaged in a relatively lively argument today over a thorny issue of statutory interpretation under the False Claims Act: how two separate statute-of-limitations provisions apply to whistleblower, or “qui tam,” actions when the federal government has not intervened in a suit brought by a private party, or relator.

“These types of actions are exceptional in many ways,” Chief Justice John Roberts observed about the qui tam suits brought under the 1863 statute that was meant to battle rampant fraud by contractors during the Civil War.

Cochise Consultancy Inc. v. United States, ex rel. Hunt stems from a more recent period of U.S. military history — the deployment of U.S. forces in Afghanistan and Iraq. Whistleblower Billy Joe Hunt alleges that Cochise Consultancy and another defense contractor defrauded the federal government in a contract to clean up munitions left behind by Iraqi forces.

The FCA helps the federal government recover some $3 billion in fraudulent contracting expenses annually, with the government taking the lead in about one-quarter to one-third of cases, while private relators initiate the rest (with the possibility of the government stepping in at any point).

If the government intervenes in a civil action brought by a relator under the statute, the relator is generally entitled to between 15 percent and 25 percent of any monetary recovery. If the government declines to intervene and the relator successfully prosecutes the action, the relator receives between 25 percent and 30 percent of the recovery.

The case before the court centers on the FCA’s two statute of limitations provisions.

As explained in David Engstrom’s preview, the law’s original statute of limitations, Section 3731(b)(1), requires lawsuits to be filed within six years of the alleged fraud. In 1986, Congress added a second statute of limitations, Section 3731(b)(2), which permits suits up to three years after “the official of the United States charged with responsibility to act in the circumstances” learns the “facts material to the right of action,” but not more than 10 years after the alleged fraud. Both statutes of limitations apply to a “civil action under section 3730,” and “whichever occurs last” controls the case.

Hunt’s FCA suit was filed in 2013, more than six years after the alleged fraud, which occurred in 2006 and 2007. Hunt argues that his case qualifies for Section 3731(b)(2)’s alternative statute of limitations because he filed suit less than three years after the relevant “official of the United States” learned of the alleged fraud in 2010.

If the federal government had intervened in Hunt’s suit, the alternative statute of limitations plainly would have applied. But the government did not intervene. The district court dismissed the suit as untimely, but the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit reversed, taking a position different from conflicting views in several other circuits. As Engstrom’s preview explained, the 11th Circuit held that relators can invoke Section 3731(b)(2) in suits in which the United States is not a party and that Section 3731(b)(2)’s three-year limitations period does not begin until the government learns of the alleged fraud, regardless of when the relator discovers it.

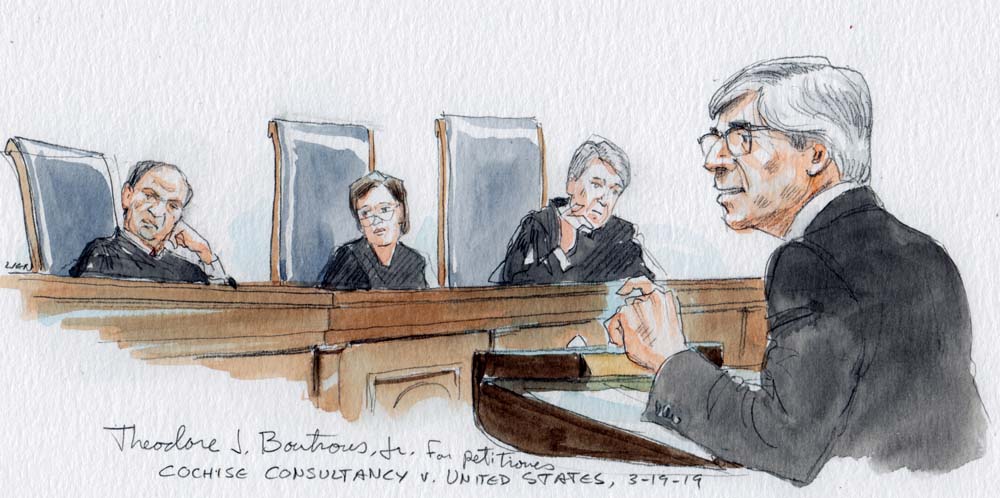

Arguing on behalf of the contractors today, lawyer Theodore Boutrous said that under the 11th Circuit’s approach, “a relator could conceal from the United States and could wait to sue for a decade and still take advantage of the principle of equitable tolling.”

According to Boutros, that approach conflicts with Graham County Soil & Water Conservation District v. United States, ex rel. Wilson, in which the Supreme Court held that the six-year statute of limitations did not apply to actions brought under an FCA provision that governs retaliation.

Graham “held that these provisions must be interpreted in context, not in isolation,” Boutrous said.

Boutrous quickly ran into difficulty. Justice Neil Gorsuch said:

I just put my cards on the table so you can play them as you wish. In Graham, we held that retaliation claims just simply aren’t covered by this provision at all, and they don’t qualify under that introductory language for either purposes of [Section 3731] (b)(1) or (b)(2). Here, you’re asking us to split the baby, as it were. And we normally don’t read the same language to mean two different things. And I believe that’s a problem you face that we did not face in Graham.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor told Boutrous that the provisions appear to give relators a longer statute of limitations than the government, but it may be important to look at the broader purpose of the FCA, which is “is to ensure that when some fraud has occurred against the U.S., that there is recovery for the United States.”

Boutrous observed that Hunt waited seven years to file his qui tam suit, “and one of the cases that creates the conflict that brings us here was eight or nine years. It is so contrary to the very essence of equitable tolling to allow someone to lie in the weeds and conceal from the United States.”

Roberts interrupted him to say that seems to be more of an “academic concern.”

The relators “know if they don’t move promptly, another relator might preempt them,” the chief justice said. “They know that if they don’t move promptly, the government itself might find out before they have a chance to file, and that would preempt their action as well. The theory of a relator just sort of, as you say, waiting in the weeds I think is not a realistic one.”

Boutrous repeated several times that statutes of limitations serve important purposes.

“Ten years in civil litigation, memories fade, people — witnesses die,” Boutrous said. “They disappear. And so the difference between six years and 10 years is a very long time.”

Justice Samuel Alito seemed most sympathetic to the contractors’ side.

“This is an interesting case because it really does create a statutory interpretation dilemma,” Alito said. “This is a terribly-drafted statute. It may serve wonderful purposes, but if I were to grade whoever drafted it—anyway, I’ll pass that.”

But “you have a real problem trying to fit this into the statutory text,” he told Boutrous.

Two attorneys argued that relators can rely on the longer statute of limitations even when the government declines to intervene in a case.

Earl Mayfield, representing Hunt, said “the absurdity here would be if the statute didn’t result in the United States obtaining more funds or if there was some anomalous result.”

Mayfield said that Congress has “built a statutory scheme that confines the very harms” that petitioners raise.

“Virtually all relators bring their suits … as soon as they get a lawyer who is able to identify the fraud and bring it forward, because otherwise … they’ll lose everything,” he said. “It would be like taking a lottery ticket and dropping it in the toilet. No one does that. And at the end of the day, every time a relator acts, no matter when he does it, whether it be year one, year five, or year ten, it is the government that ultimately benefits.”

Matthew Guarnieri, an assistant to the U.S. solicitor general, also argued in support of Hunt’s position.

“The key thing to keep in mind” with respect to the policy result, Guarnieri said, “is that a relator is permitted to sue to vindicate an interest of the United States. The United States is the injured party in all of these cases. The United States is a real party in interest regardless of whether or not it elects to intervene in the action, the majority of any recovery would go to the United States. And in that context, it made good sense that Congress chose to make the tolling rule in (b)(1) applicable based on the knowledge of the injured party; that is, the United States.”

Despite some persistent questioning from Alito, both Mayfield and Guarnieri apparently felt confident enough in their arguments to finish well before their time had expired.

***

Past case linked to in this post:

Graham Cty. Soil Water Con. v. U.S. ex Rel. Wilson, 545 U.S. 409 (2005)

[Disclosure: Goldstein & Russell, P.C., whose attorneys contribute to this blog in various capacities, is among the counsel on an amicus brief in support of the respondent in this case. The author of this post, however, is not affiliated with the firm.]