Argument analysis: Justices divided and hard to read on partisan gerrymandering

Today the Supreme Court heard oral argument in a pair of cases that could prove to be among the most consequential of the term. The cases involve allegations that state officials engaged in unconstitutional partisan gerrymandering – that is, they went too far in taking politics into account – when they drew election maps in North Carolina and Maryland. After over two hours of debate this morning, there were clear divides among some of the justices, but it was much less clear how the court is likely to rule.

The two cases arrived at the Supreme Court less than a year after the justices sidestepped a ruling on the merits in the Maryland case and another case alleging partisan gerrymandering in Wisconsin. As last year’s cases reflected, the issue of partisan gerrymandering is one with which the justices are very familiar, but which has also proven very difficult. In 2004, the Supreme Court was sharply divided in a partisan-gerrymandering challenge to Pennsylvania’s redistricting plan. Citing a lack of a workable standard to determine when party politics crosses a line and plays too influential a role in redistricting, the court’s four more conservative justices at the time believed that courts should never have a role in reviewing claims of partisan gerrymandering. Four of the court’s more liberal justices argued that courts should police partisan-gerrymandering claims, while Justice Anthony Kennedy – who has since retired – staked out a middle ground: He argued that the Supreme Court should not review the Pennsylvania case, but he left open the possibility that courts could review partisan-gerrymandering claims in the future if a manageable standard could be established.

When the justices announced in 2017 that they would review a partisan-gerrymandering challenge to the redistricting plan that Wisconsin’s Republican-controlled legislature drew for the state’s general assembly in 2011, it seemed like the Supreme Court might finally resolve the partisan-gerrymandering issue once and for all. Two months later, the justices added another case to their docket: a challenge by Republican voters to a single federal congressional district, drawn by Democratic officials, in Maryland.

But in June 2018, the Supreme Court sent both cases back to the lower courts – without ruling on either the merits of their claims or on the broader question of whether courts should review partisan-gerrymandering claims generally. The justices agreed unanimously that the plaintiffs in the Wisconsin case had not shown that they had a legal right, known as standing, to challenge the entire statewide map. And, in the Maryland case, they emphasized that the case came to them in the early stages of the dispute. The plaintiffs had asked the lower court to temporarily block Maryland from using the 2011 map until it could decide whether the map is constitutional, and the standard of review was therefore lenient: All that mattered was whether the lower court’s ruling was unreasonable – which, the justices concluded, it was not.

The Maryland case went back to the lower court, which held a hearing last fall. The plaintiffs in that case argued that when Democratic election officials drew new district boundaries after the 2010 census, the officials only had to shift about 11,000 voters. But instead, the officials added 24,000 new Democratic voters to the district and took out 66,000 Republican voters – all, the plaintiffs say, to retaliate against them for their support of Republican candidates in the past. The lower court agreed with the plaintiffs and ordered the state to draw a new map for the 2020 election. The state appealed to the Supreme Court, which announced earlier this year that it would review both Lamone v. Benisek, the Maryland case, and Rucho v. Common Cause, the North Carolina case.

The North Carolina case is a challenge to the state’s federal congressional map, which was adopted by the state’s Republican-controlled legislature. In 2016, a lower court struck down the first map drawn after the 2010 census, ruling that two districts were unconstitutional racial gerrymanders. The legislature drew a new map in 2016, which is the subject of the current challenge. But in January 2018, the lower court found that the new map was the product of an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander and ordered the state to draw a new one. The state’s Republican legislators appealed to the Supreme Court, which ordered the lower court to take a new look at whether the plaintiffs have standing to sue in light of the justices’ decision in the Wisconsin case.

When the case went back to North Carolina, the district court again struck down the 2016 map. It agreed both that the plaintiffs have a legal right to sue and that the new map was the result of partisan gerrymandering, and it blocked the state from using the map after the 2018 election.

Arguing for the Republican legislators this morning, former U.S. solicitor general Paul Clement urged the justices to stay out of the fray. The Constitution gives responsibility for drawing congressional districts to the political branches, he emphasized: first to state legislatures, and then to Congress itself, acting as a supervisor. There is no role for the courts, particularly because plaintiffs in partisan-gerrymandering cases have repeatedly failed to identify a workable standard for courts to use in reviewing such claims.

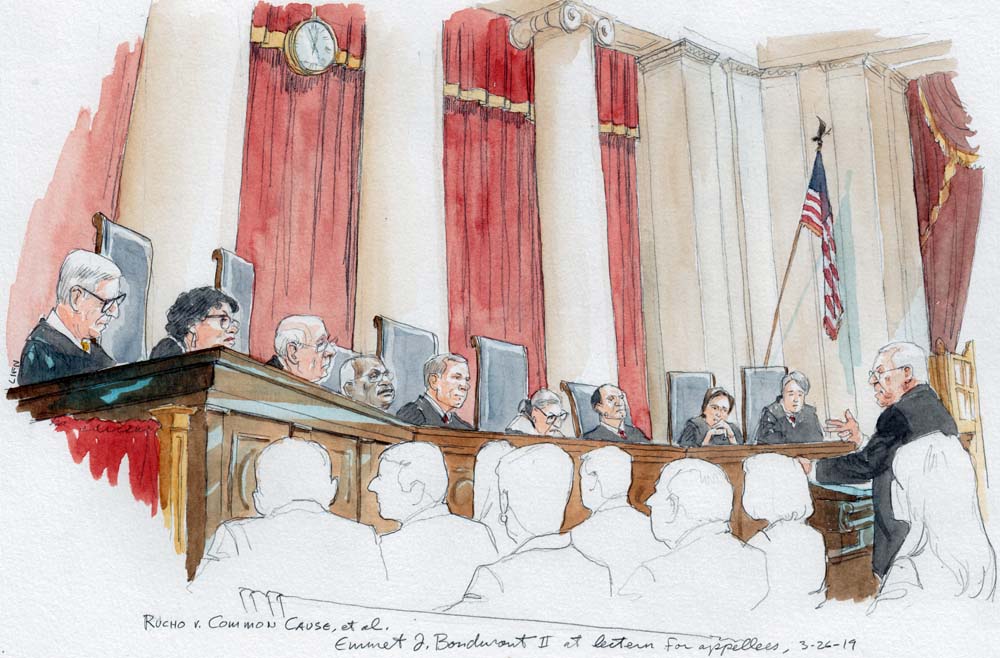

Justice Neil Gorsuch seemed to agree that the problem of partisan gerrymandering is one that should be left for the political branches of government to deal with. He recalled that, in the court’s previous partisan-gerrymandering arguments, lawyers for the challengers had argued that the courts are the only institution that can remedy partisan gerrymandering. But, he posited, states have in fact taken action to address the problem. Why should we wade into this, Gorsuch asked Emmet Bondurant, who argued on behalf of one group of challengers in the North Carolina case, when that alternative exists?

Justice Brett Kavanaugh echoed this concern. He told Allison Riggs, who argued for a second group of challengers in the North Carolina case, that he understood “some of your argument to be that extreme partisan gerrymandering is a problem for democracy.” Referring to activity in the states and in Congress to combat partisan gerrymandering, Kavanaugh asked whether we have reached a moment when the other actors can do it.

Riggs responded that North Carolina, at least, is not at that moment. When Kavanaugh responded, “I’m thinking more nationally,” Riggs shot back that “other options don’t relieve this Court of its duty to vindicate constitutional rights.”

Chief Justice John Roberts also seemed to suggest at one point that the political process could take care of partisan gerrymandering. Partisan identification, he told Bondurant, is not the only thing on which people base their votes. A vote may hinge on a specific candidate, or who is at the top of a ticket, Roberts observed. When Bondurant pushed back with references to findings by social science experts, Roberts countered that “a lot of predictions turn out to be wrong.” In the 2018 election, for example, a “lot of things that were never supposed to happen, happened.”

Justice Stephen Breyer searched out loud for a formula that would capture what he characterized as the “real outliers.” He proposed a standard that would bar challenges to districting maps created by independent redistricting commissions, but that would deem a map an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander if a party wins a majority of the statewide vote but the other party wins more than two-thirds of the available seats.

Clement was unenthusiastic, telling Breyer that there is “so much in that that I disagree with.” Citing now-retired Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, Clement referred to any problems created by partisan gerrymandering as “largely self-healing.” By contrast, he warned darkly, if the Supreme Court were to rule that courts can review partisan-gerrymandering claims, partisan-gerrymandering cases will come to the Supreme Court – which will have to review them, because redistricting cases are among the narrow set of cases with an automatic right of appeal to the Supreme Court – “in large numbers.” “And once you get into the political thicket,” Clement continued, “you will tarnish the reputation of this Court for the other cases where it needs that reputation for independence.”

Riggs offered a similar appeal, although with a very different perspective, toward the end of her argument. She stressed that, “with all due respect, Justice O’Connor was not correct. This isn’t self-correcting.” And although “the reputation of the Court as an independent check is an important consideration,” “the reputational risk to the Court of doing something is much, much less than the reputational risk of doing nothing, which will be read as a green light for this kind of discriminatory rhetoric and manipulation in redistricting from here on out.”

In the Maryland case, Steven Sullivan, the Maryland solicitor general, argued for the state, which agrees that the Supreme Court should establish a workable standard to ferret out unconstitutional partisan gerrymandering but has nonetheless urged the justices to overturn the lower court’s decision in this case.

Sullivan quickly ran into questions from Justice Elena Kagan, who told him that the partisanship in this case was “excessive” “under any measure.” The shift of Republicans out of and Democrats into the district ensured that Republicans will never win this seat again and that they now have only one member in Maryland’s eight-member congressional delegation, Kagan emphasized, even though they make up 35 percent of the state’s population.

Kagan later tried to make the point that, if the Supreme Court were to rule for the plaintiffs in the Maryland case, it would not actually lead to a flood of redistricting lawsuits. This case is easy, she told Michael Kimberly, who argued on behalf of the plaintiffs, because of the “bragging” by state officials about how they had drawn the districts to favor Democrats. But once the court has made clear that partisan gerrymandering is unconstitutional, she continued, there wouldn’t be any bragging, and it “would really raise the bar” for plaintiffs to show that the alleged gerrymandering had had “dramatic effects.” And in the end, Kagan contended, lawsuits would only target the “worst of the worst” in partisan gerrymandering.

Roberts appeared sympathetic to the plaintiffs’ challenge, which rested on the First Amendment. It does seem, he told Sullivan, like the state is retaliating against Republicans. What’s wrong with that argument?

When Sullivan responded that the plaintiffs’ First Amendment retaliation theory had never been used before in this context, Roberts responded that he didn’t know why it wouldn’t apply here. Do you think, Roberts asked, that it’s all right to retaliate against Republicans from this district because of how they voted?

Kavanaugh asked the attorneys in each case whether the Constitution requires proportional representation – that is, that a party’s share of seats be proportional to the statewide vote. He was also interested in whether proportional representation might be a workable standard for reviewing partisan-gerrymandering claims. He lamented that “everyone seems to be running away” from proportional representation “even though it all seems to come back to proportional representation.”

During the oral arguments in last term’s partisan-gerrymandering cases, Roberts was deeply concerned about the effect on the Supreme Court’s institutional reputation if it were to get involved in partisan-gerrymandering cases. Although Roberts may not have voiced those worries today, Clement clearly tried to evoke them. Even if the court’s four more liberal justices are all in favor of the court’s getting involved in partisan-gerrymandering cases, they would need to pick up one more vote – in all likelihood, from either Kavanaugh or Roberts – but it’s not clear after today’s argument whether they can enlist at least one of those justices.

This post was originally published at Howe on the Court.

Posted in Merits Cases

Cases: Rucho v. Common Cause, Lamone v. Benisek