Argument analysis: Peace cross appears safe, if not stable

on Feb 27, 2019 at 4:07 pm

For nearly a century, a 40-foot-tall stone and concrete cross has stood on a traffic median in the Washington, D.C., suburbs, just a few miles from the Supreme Court. But seven years ago, a group of local residents filed a lawsuit seeking to have the cross removed. They argue that the presence of the cross on public land violates the Constitution, which bars the government from establishing an official religion and favoring one religion over another. The state of Maryland, which owns and maintains the cross, and the American Legion, which built it, counter that the cross – which is badly in need of repair – is simply a secular war memorial. Today the justices heard oral argument in the dispute, and it seemed likely that the cross will survive the challenge, even if the court’s ruling proves to be a relatively narrow one that allows the peace cross and other historical monuments to stand while making clear that new religious symbols may not pass muster in the future.

Neal K. Katyal for petitioners (Art Lien)

The cross was dedicated in 1925 in Bladensburg, Maryland, as a memorial to the 49 soldiers from the area who were killed during World War I. A plaque at the bottom of the cross contains the names of those soldiers, as well as a quote from President Woodrow Wilson; smaller memorials commemorating other conflicts – from the War of 1812 to the September 11 attacks – are nearby.

A federal district court ruled for the state and the American Legion. In its view, the state’s ownership and maintenance of the cross do not violate the Constitution because the state has been primarily concerned with maintaining traffic safety and honoring veterans, rather than promoting religion.

But the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit reversed. To determine whether the cross violates the establishment clause, the court of appeals applied a test from the Supreme Court’s 1971 decision in Lemon v. Kurtzman, which focuses on whether a law or practice has a secular purpose, whether its principal effect advances religion, and whether the law or practice creates an “excessive entanglement with religion.” In this case, the court of appeals reasoned, the average person would think that the cross is intended to endorse religion because the cross dominates the other war memorials in the vicinity and has long represented Christianity.

The American Legion and the state asked the Supreme Court to weigh in, which it agreed to do last fall. At today’s oral argument, lawyer Neal Katyal – who represented the state – emphasized that the cross has stood in its current location for nearly all its history without any challenge. And both Katyal and Jeffrey Wall, the deputy U.S. solicitor general, who argued as a “friend of the court” on behalf of the state and the American Legion, stressed two other themes. First, as in the Supreme Court’s decision in Town of Greece v. Galloway, which upheld a New York town’s practice of beginning its town council meetings with a prayer offered by members of the clergy, there is a long tradition of displaying crosses. Second, in this particular context the cross has a unique and secular meaning, because it is closely associated with World War I and, more broadly, with “sacrifice and death,” as Wall put it.

Acting Solicitor General Jeffrey B. Wall (Art Lien)

Katyal and Wall faced significant pushback from three of the court’s more liberal justices. Justice Sonia Sotomayor was incredulous at the idea that there was a long tradition of crosses in public places, telling Wall that “I don’t know of a Founding Father, town or state that put a 40-foot cross on government property.” To the contrary, she noted, “a lot of Founding Fathers, including George Washington,” were “exceedingly careful to ensure that references to God were as neutral as possible to as many religions as possible.”

Justice Elena Kagan repeatedly resisted the idea that the cross can have a secular meaning, telling Wall that the cross “invokes the central theological claim of Christianity that Jesus Christ, the Son of God, died on the cross for humanity’s sins and that he rose from the dead.”

Sotomayor echoed this idea, observing that for very religious Christians, suggesting that the cross is secular is itself blasphemy.

Ginsburg drew on her own travels to posit that the cross was not a universal symbol for all soldiers who were killed during World War I. On some of the World War I battlefields she has visited, she told Katyal, Stars of David – rather than crosses – mark the graves of Jewish soldiers.

Arguing on behalf of the American Legion, lawyer Michael Carvin offered a more sweeping test, under which virtually all religious symbols would generally be constitutional except, he explained, “in the rare circumstances where they’ve been misused to proselytize.”

Michael A. Carvin for petitioners (Art Lien)

Carvin’s proposed standard met with skepticism not only from the court’s more liberal justices but also, significantly, from some of its more conservative members.

Justice Neil Gorsuch was one of those skeptics. If we “abandon Lemon’s endorsement test because it’s become a dog’s breakfast,” Gorsuch queried, what’s the difference between proselytizing and endorsement?

Chief Justice John Roberts was also skeptical, although for a slightly different reason. He noted that what Carvin had initially advertised as a “pretty concise test” “degenerates pretty quickly into” “kind of a fact-specific test” – which, Roberts seemed to suggest, the court would want to avoid.

Monica Miller argued on behalf of the American Humanist Association and the local residents challenging the cross. After Miller responded to a hypothetical from Justice Samuel Alito about whether a town could put up a Star of David as a memorial to the victims of a shooting at a synagogue by answering that a “45-foot Star of David in the middle of a roadway would be a problem,” Gorsuch broached a question about whether Miller’s clients should have a legal right to challenge the cross at all. There aren’t many areas of the law, Gorsuch told Miller, where people can sue over an offense because it is “too loud.” Why, Gorsuch asked, should the Supreme Court have to “dictate taste?” Shouldn’t it instead apply its normal rules and require more than that someone was merely offended by the presence of the cross?

Roberts chimed in briefly, asking Miller whether it would be enough to have one letter from one person who was offended by the cross. But the justices then moved on to an issue that would dominate much of Miller’s time at the lectern: If Miller were to prevail, would other religious symbols around the country also have to come down?

The justices asked about crosses – including a question from Alito about a cross in Gettysburg dating back to 1888 – but also about other symbols. Roberts noted that a Native American totem pole can have spiritual significance. Would it need to be torn down, he asked Miller, if it were on federal property?

Miller tried to assure the justices that her opponents were exaggerating the number of crosses on public land, telling them that it was “more like 10 or maybe 20.” But that response didn’t seem to allay the justices’ concerns. Justice Stephen Breyer, who had been relatively silent, proffered a narrow resolution that would allow the peace cross and other historical monuments to stand, while recognizing that times have changed in the United States, so that future monuments would be inappropriate. In light of the historical context of this case, Breyer asked Miller, what do you think of saying “yes, ok, but no more?” “We’re a different country now, and there are 50 more different religions” than there were when the cross was erected nearly a century ago.

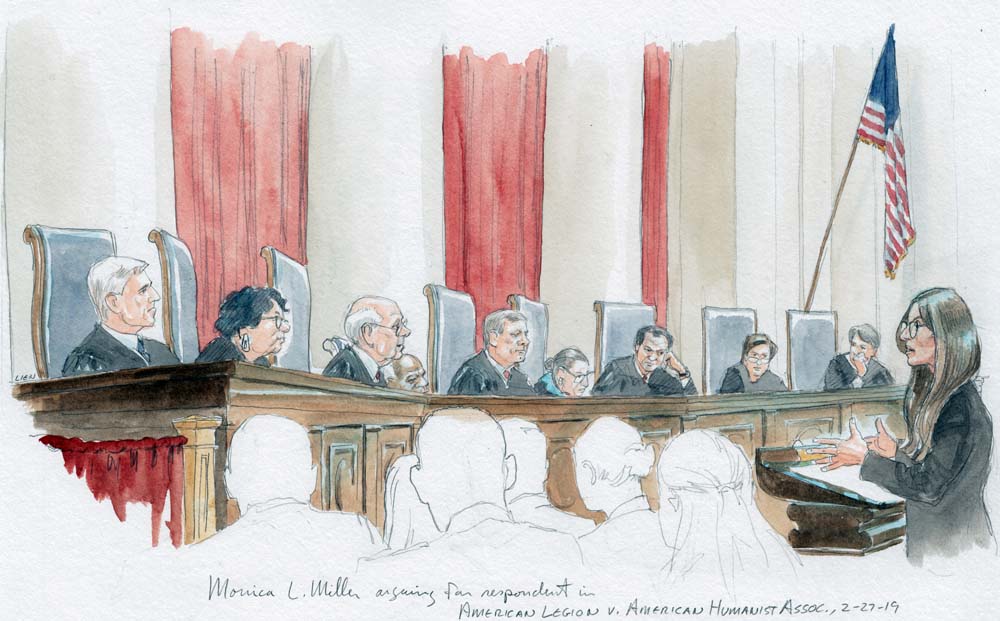

Monica L. Miller for respondent (Art Lien)

Miller was unenthusiastic, but Kagan was more receptive to Breyer’s idea. “There’s something quite different about this historic moment in time,” Kagan agreed.

Miller and Katyal did agree on one thing: There is no need, at least in this case, for the court to jettison the Lemon test. During his rebuttal, Katyal told Sotomayor that it would be “unnecessary and unwise” to do so, because this is an easy case; instead, he argued, the court should wait for a case in which the decision whether to use the Lemon test might actually make a difference.

Miller described the Lemon test as “very useful.” That prompted Justice Brett Kavanaugh to retort, “How could it be useful when we haven’t used it?”

Gorsuch was the most forceful in calling for the end of the Lemon test, observing that although it has been a long time since the Supreme Court has used the test, the federal courts of appeals have had to grapple with it. “Is it time,” Gorsuch inquired, “for this Court to thank Lemon for its service and send it off?” After today’s oral argument, the answer to Gorsuch’s question may well be no, but we’ll know more by summer.

This post was originally published at Howe on the Court.

* * *

Past cases linked to in this post:

Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403 U.S. 602 (1971)

Town of Greece v. Galloway, 134 S. Ct. 373 (2013)

[Disclosure: Goldstein & Russell, P.C., whose attorneys contribute to this blog in various capacities, is counsel on an amicus brief in support of the petitioners in this case. The author of this post, however, is not affiliated with the firm.]